Several hundred researchers gathered for the Fifth Annual New England Tuberculosis Symposium, sponsored by the Harvard Global Health Institute, for sessions covering topics that ranged from new findings on how the tuberculosis bacteria grows, to the body’s immune response to infection, to the latest progress toward a more effective vaccine.

Katherine C. Cohen/Harvard Staff Photographer

A focus on battling tuberculosis

Regional symposium draws researchers to share their insights

Scientists from around New England gathered at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard on Thursday (June 23) to share the latest advances in understanding of the biology of tuberculosis and how best to attack the disease.

Several hundred researchers gathered for the Fifth Annual New England Tuberculosis Symposium, sponsored by the Harvard Global Health Institute, for sessions covering topics that ranged from new findings on how the tuberculosis bacteria grows, to the body’s immune response to infection, to the latest progress toward a more effective vaccine.

Sarah Fortune, assistant professor of immunology and infectious diseases at the Harvard School of Public Health (HSPH) and one of the event’s organizers, said that although several participants came from outside the region, even from as far away as South Africa, the event’s focus was on building relationships among New England scientists studying tuberculosis. This community-building aspect allowed them to share results and get to know each other with the aim of easing future knowledge sharing and smoothing the path to potential future collaboration.

“I really am a big believer in community,” Fortune said. “The goal is to bring together the regional groups.”

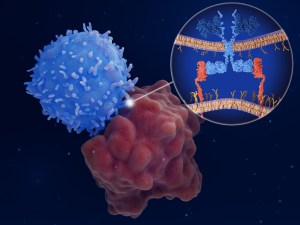

Fortune and Amy Barczak, another event organizer, an instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School, and a physician at Harvard-affiliated Massachusetts General Hospital, said that public interest in tuberculosis issues has risen greatly in recent decades because of the disease’s close association with HIV and AIDS. The incidence of tuberculosis globally has risen dramatically since the early 1990s, since it has become one of the leading causes of death of AIDS patients, whose immune systems are compromised by the human immunodeficiency virus.

More recently, Fortune said, an increase in funding for research against the disease, notably by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, has stimulated work in the field. The recent rise of drug-resistant tuberculosis, including strains nearly untreatable because of their resistance to drugs, has further focused attention on the ailment.

Work toward a tuberculosis vaccine continues, with some candidates in clinical trials. Even so, vaccines currently in development would reduce susceptibility by just 10 to 20 percent, Barczak said, and represent incremental steps toward a vaccine that one day provides complete protection, which Fortune said appears to be far in the future.

Still, researchers are moving ahead in their understanding of the tuberculosis bacteria’s biology. Bree Aldridge, a postdoctoral fellow in Fortune’s lab, presented recent findings on how the bacteria grow.

Aldridge described experiments that isolated single bacteria in microfluidic channels, allowing images of them as they divide and grow. Researchers observed for the first time that the bacteria divides and grows asymmetrically, with most of the growth occurring on one side of its body rather than uniformly. One effect of this is that when the cell divides, the daughter cell that inherits the faster-growing end continues rapid growth. The daughter cell inheriting the slower-growing side grows less quickly.

“We were pretty amazed to see this growth,” Aldridge said. “We were expecting to see polar growth, but not unipolar growth.”

Researchers also observed that the cells divide after a certain amount of time, rather than when they reach a certain size. These factors create a diverse population of tuberculosis bacteria with cells of different sizes and growing at different rates. Treatment with antibiotics showed that the population diversity helps the bacteria survive, with the faster-growing population more susceptible to antibiotics, and the slower-growing population more resistant.