Depending on the season, 35 to 70 percent of the produce served at Harvard is from fewer than 250 miles away, the definition of regional, according to Harvard University Hospitality and Dining Services.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

From plants to plates

How Harvard’s cooks serve up 5 million meals a year

Dining at Harvard in the 17th century meant a meager diet of beer and bread, while foul food in the 18th century spawned America’s first student protest, the Great Butter Rebellion of 1766. (The rallying cry was “Behold, our butter stinketh!”) But that was then. These days, Harvard’s chefs have 4,000 recipes on hand, serve vegan entrees, and embrace international cuisines. The most popular undergraduate meal now is Korean barbecued beef.

Keeping Harvard fed in the 21st century is a mammoth logistical effort, almost a military operation. The 12 University-owned restaurants, 13 dining halls, and many catered events now serve about 26,000 meals a day — about 5 million a year. University cooks make 40,000 gallons of soup, enough to fill a pool for a swim meet. Students consume 40,000 pounds of regional squash annually, and nearly as much in local tomatoes.

Numbers that big require big systems: the institutional means to buy, transport, store, cook, and serve the food, and to clean up afterward. At Harvard, those systems run on two interlocking themes: good taste (for the diners) and good stewardship (for the environment).

There has been an increasing campus emphasis in the past decade on fresh, delicious food, as well as on food that is both sustainable (grown and processed using minimal energy) and regional (grown close to Cambridge).

Depending on the season, 35 to 70 percent of the produce served at Harvard is from fewer than 250 miles away, the definition of regional, according to Harvard University Hospitality and Dining Services (HUHDS). Produce served at Harvard is “local and sustainable, mostly,” said Martin Breslin, HUHDS’s director for culinary operations, who trained as a chef in Ireland. “But it shifts as the season shifts.”

In addition to the thousands of recipes in the HUHDS database, master chefs gather on many afternoons and evenings to test still more — with Breslin among them. Such variety is a long way from the beer and bread of the 17th century, when poor food could topple a Harvard president.

But past eating practices have something in common with Harvard’s current approach to food: It should be local, whenever possible.

In the 17th century, many families paid for Harvard’s tuition with goods that soon showed up on College menus: cattle, mutton, wheat, corn, rye, barley, butter, eggs, cheese, turnips, apples, and parsnips. Each family in the colony gave one peck of corn — or 12 pence — to “the College at Cambridge.” The College butler purchased the School’s provisions from local merchants, though some goods, such as sugar, still came from overseas.

Today, Harvard buys much of its produce (and all of its milk and cheese) from a consortium of 250 New England farms. The University also buys much of its processed food from 29 nearby vendors, who make bread, cider, bagels, pasta, salsa, spices, peanut butter, tofu, and other products.

Another echo of the old days is the way Harvard handles its food-related waste: It’s composted, whenever possible. Every day, nearly two and a half tons of recycling and compost come from the undergraduate dining halls alone. And composting is catching on in Harvard restaurants, offices, and even dormitory rooms.

Harvard’s systems provide a case study of where food comes from, how it is prepared, and where the remains go — a narrative that can be summed up as “plant to plate to plot.”

Where the plants are

In good weather, Jim Ward spends at least part of his day driving a 1986 Model 2555 John Deere tractor, a slab-sided green machine with tall, mud-caked tires.

With his brother Bob, he is co-owner of Ward’s Berry Farm in Sharon, Mass., a 150-acre family operation. It’s the only regional farm with which Harvard has a direct relationship. Other farms deal with the University through a Boston-area broker, Costa Fruit Food and Produce.

Ward’s has 120 acres of corn, peas, beans, rhubarb, lettuce, squash, tomatoes, garlic, and other vegetables. Fruit trees and bushes take up 30 more acres. There is a long field of 7,000 blueberry bushes, acres of strawberries, a stand of dwarf cherry trees, and a grove of peach trees that this summer will yield their first fruit. The farm has 30,000 tomato plants on 10 acres, a big operation for New England. Half are heirloom varieties that preserve genetic diversity and provide good taste.

For Harvard, Ward’s signature crop is squash — 40,000 pounds of it harvested each fall and storable through the winter, just as it was for the first colonists. Some heirloom varieties on the farm were around centuries ago, he said, including New England blue hubbard, Long Island cheese, and Georgia candy roaster. This last variety matures into pale tubes as long as artillery shells.

“It sustained a lot of families before refrigeration,” he said of the old-fashioned squash. “A hundred years ago, by March, you would probably be sick of it.”

But for Harvard students, the main lesson should be the pleasure of eating locally, said Ward, a champion of cooking shows and of food writer Michael Pollan. “Savor (a food) when it’s in season,” Ward said. Meanwhile, he is grateful for Harvard’s buy-local ethic, and feels lucky to be in business at a time, Ward said, “when there’s a little bit of love for farmers.”

From dock to kitchen

In August, at the height of harvest season, Ward will spend his days in a breezy, shaded loading dock at the farm, grading tomatoes, talking to his pickers, and sending out delivery trucks.

Harvard has its own food unloading dock, at 80 JFK St., at Kirkland House, across from the Harvard Kennedy School. The operation is ground zero for the tons of produce and other goods that arrive five days a week, in every season, to feed the University’s hefty appetite.

Harvard’s high standards for food safety start right at that front door, said Breslin, whose office is a few steps away. Food receivers are trained to inspect visually anything that comes in, and to check temperatures.

The University follows — and surpasses — a systematic, preventive set of food industry guidelines called Hazard Analysis Control Point. The guidelines address potential physical, chemical, and biological hazards that can accompany perishable organic matter.

All cooked food, for one, is stored at 41 degrees Fahrenheit or lower. Cooking takes place at 165 degrees or higher, and at 195 degrees for soups and sauces that are bagged and quick-chilled.

Past the loading dock, through a nearby door, is the commissary area, the first kitchen step for much of the food pouring into the Harvard pipeline, and the entry point to a spacious, clean set of rooms called the Culinary Support Group.

The everyday phrase there is mise en place — French for “putting in place” — a system used in professional kitchens for cleaning, cutting, and arranging everything needed for the day’s recipes.

A weekday staff of three receivers, four prep cooks, two soup makers, and four cleaners handles the details, starting at 5 a.m. They are overseen by two men wearing tall white chef’s toques made of paper. Richard Spingel, a 39-year Harvard veteran who started in high school as a pot washer at Radcliffe College, is chef production manager. Brian Corcoran is executive sous chef in charge of food quality, Culinary Support Group production, and the loading dock.

A few steps away is the “kettle station,” which makes the tens of thousands of gallons of soup, sauce, and pasta consumed at Harvard every year. (Harvard’s perennial favorite soup, said Breslin, is New England clam chowder.)

It takes up to an hour to make a 73-gallon batch of soup in the gleaming steam-jacket kettles that cook and stir at the same time. Behind the kettles, a temperature control panel blinks. In front of them is an air-compressed batch pump that bags soup and sauce in three-quarter-gallon spurts.

After being tagged with a recipe, date, and tracking code, each bag is fed into a tanklike chiller that brings the content’s temperature down from 195 to 41 degrees within 20 minutes. Food and Drug Administration guidelines say chilled product has a shelf life of 14 days; Harvard stores it for no more than three days before it is eaten. “We cut that way back,” said Breslin.

“Cook-chill” operations like this are now common among universities, he added, because they offer “an energy-efficient, cost-efficient, consistent way to cook on a large scale.”

Up until the late 1990s, all the food prepared for Harvard House dining halls was cooked in one place, boxed in warmers, and shuttled along underground tunnels in narrow electric carts. Now it’s cooked “15 minutes before it’s eaten,” said HUHDS spokeswoman Crista Martin.

Starting in 1997, all of Harvard’s House kitchens were renovated, in a grand plan hatched by HUHDS executive director Ted A. Mayer, who oversees 600 employees who cook, serve, cater, and educate. The last renovated kitchen, at Dunster-Mather, was finished in 2005.

Part of the challenge, said Martin, is Harvard’s mandatory, unlimited board program. All students have a stake in the food plan, including those with special dietary needs and those with strong culinary desires. It makes for a food system that is vastly more complicated than it once was, but also one that is more flexible, diverse, and accommodating than ever.

As one example, 33 percent of the entrees now served in Harvard Houses are vegetarian. “We have to meet everyone’s needs,” said Martin, “and vegetarian is one of those.”

Dishes are no longer the American and Western European standards that filled menus 20 years ago; they are derived from a medley of world cuisines. Of Harvard’s 4,000 database recipes, she said, about 1,000 are used routinely in the Culinary Support Group operation. House menus rotate every month. The menus, said Breslin, “are always about choice.”

Food in the classroom

Harvard students have a choice of academic courses about food too — and the options are increasing. Professors in the past have used food as a pathway to studying history, economics, culture, literature, sustainability, and the environment. The undergraduate General Education curriculum launched last fall shook loose more ways to view food as a window on the world. This year, “Nutrition and Global Health” examined malnutrition, food security, food-related disease states, and other issues affecting global health.

“American Food: A Global History” probed what is American about food, and its centrality to the cultural experience beginning in the 17th century. And next fall a Gen Ed course called “Science and Cooking” will debut at the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, pairing eminent researchers with world-class chefs, who will use cooking to illustrate “soft matter physics” (gels and suspensions).

HUHDS also emphasizes education through its Food Literacy Project, which includes events, literature, and 15 paid student employees. The project concentrates on four areas where food and society intersect: sustainability, nutrition, food preparation, and community. The project, founded in 2005, works in partnership with nutritionists from the School of Public Health, HUHDS dieticians, and other groups like the Office for Sustainability and the Resource Efficiency Program.

“Food is that thing everyone can get in touch with,” said Martin.

How Harvard eats Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Top chef

Director for Culinary Operations Martin Breslin stands at the kettle station, which makes the tens of thousands of gallons of soup, sauce, and pasta consumed at Harvard every year.

Fun food

Richard Spingel, chef production manager, wears a Veritas chef’s coat while he works in the culinary lair below Kirkland House.

Spreading the word

Harvard University Hospitality & Dining Services works closely with the Harvard School of Public Health’s Nutrition Department, who put together this snazzy and informative guide that hangs in the dining halls.

Ribbon blender

Chef Breslin stands at the ribbon blender, which minimizes handling and can disperse ingredients within 30 seconds.

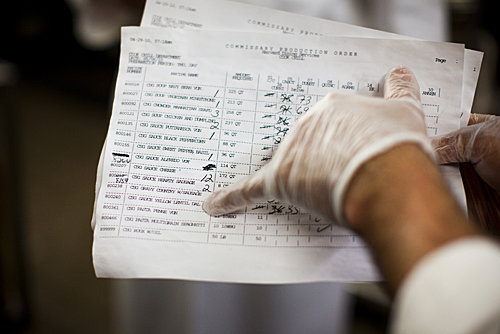

Production details

Chef Breslin and Executive Sous Chef Brian Corcoran go over the production list for the day’s menu.

Saucy

Here, the list of daily soups and sauces that will be prepared includes staples like alfredo and puttanesca, while mouthwatering Manhattan seafood chowder is also on the menu.

Tunnel vision

Chef Spingel chats inside the underground tunnels of Kirkland House, where most of Harvard’s meals are dreamed up and executed.

Truth and waffles

Veritas waffle machines show some school pride, and students can make buttermilk waffles (above) or multigrain.

Radish

Jim Ward, who co-owns Ward’s Berry Farm in Sharon, Mass., plucks fresh radishes from the dirt. His farm is one of a consortium that provides local produce to Harvard.

A seed in the hand …

… is worth a ton in the bush. Here, Ward squats between rows of plants as the much-needed sun does its work from above.

The producer

Ward holds a tiny blossom from a strawberry plant.

Harvest

Ward looks over some of his crops; behind him, a sweeping view of the fields.