File Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

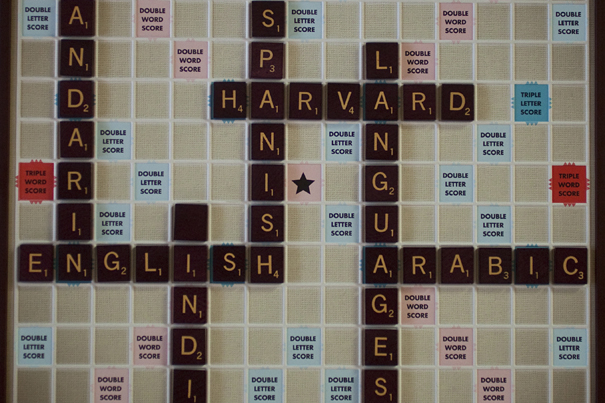

Language of learning

With hundreds of courses, Harvard’s linguistic breadth is unmatched nationally

Descending the cafeteria stairs at the Harvard Kennedy School (HKS), Ildiko Voller-Szenci greeted a classmate from Germany. A few steps later, she hailed a friend from Ecuador. Then she encountered one of the School’s executive education groups, composed of students from the far corners of the world. A sprinkling of languages peppered the hallway conversations.

“The languages spoken here and the connections that they represent to the world are just amazing,” said Voller-Szenci, who is Hungarian but also speaks English, French, and Russian.

Such diversity — HKS students come from more than 70 countries — is mirrored across the University, which has 4,131 full-time international students. That eclectic mix makes for a lush linguistic landscape, one that becomes even richer after factoring in the more than 80 ancient and modern languages taught through the Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS) and other Schools.

In an increasingly global economy, mastery of languages is often a critical component to success. Languages have long been a pivotal part of Harvard’s curriculum and a key to learning. Their study, University educators say, develops cognitive skills, fosters connections to foreign markets, preserves ancient traditions and histories, and cultivates a crucial understanding and appreciation of the world.

An FAS course booklet lists the expected German, French, and Spanish. But it also lists Akkadian, Avestan, Kikongo, Old English, Sogdian, Twi, Scottish Gaelic, Urdu, and Uyghur. The myriad choices amount to a crossword puzzle fan’s paradise.

Simply put, said Diana Sorensen, Harvard’s dean of arts and humanities, “The University offers the most comprehensive language studies program in the nation.”

In addition to studying many languages, students also are enrolling in a growing array of classes that reflect the widening ripples of a globalized world.

Sorensen, who is also James F. Rothenberg Professor of Romance Languages and Literatures and of comparative literature, has spearheaded development of the Foreign Language Advisory Group, a collection of language teachers from across the University who meet monthly to explore professional development opportunities and new language initiatives and innovations.

For the past three years, Sorensen and her group have worked to expand the language curriculum to include “bridge” courses involving history, art, and culture, which are taught in a foreign language, and to build connections between the language courses and the content courses taught at upper levels.

Cross-cultural classes

Students now can take courses on China’s Cultural Revolution, taught in Mandarin, or learn about the history and politics of the Islamic world in a class taught in Arabic.

“We were noticing that while students would get to a certain level in their language classes, they needed further encouragement to become more proficient and more deeply immersed in everything that a language can make available to them,” said Sorensen. “These courses help students understand that a language and its culture are profoundly intertwined, and that with sustained study it is possible to reach higher levels of proficiency and immersion in the cultural realm.”

Understanding another part of the world better, said Sorensen, also is an avenue for transcultural understanding.

“When you can understand that culture in its language, and its whole outlook, you are immediately receptive to areas where conflict could be averted,” she said. “I do think if we want to train global citizens and global leaders, having them equipped with this kind of transcultural literacy at a deep level is one of the goals of the university of the 21st century.”

The Foreign Language Advisory Group also has created a course for graduate students who teach languages at Harvard, one that examines the complex nature of language acquisition and specific teaching practices.

Sorensen said the panel gives “language teaching a stronger profile at the University, so it is seen as a crucial aspect of one’s cultural training.”

For Russian native Maria Polinsky, who studies languages’ complex architecture for a living, exploring another language offers students more than just the chance to experience another culture. Such study challenges the brain and helps to develop key cognitive skills. Polinsky, professor of linguistics, said that while languages offer important windows into culture, folklore, film, and literature, their ability to help people build up the executive function of the brain is an equally compelling attraction.

“By teaching students languages, we are helping enhance their cognitive functions, keeping their brains a little more active,” she said.

Polinsky said studies suggest that people raised in bilingual households develop a much stronger executive function, or ability to multitask. Research also indicates that bilingual children are much less likely to succumb to dementia later in life.

According to Polinsky, it’s not too late for college students to reap the mental benefits that come from learning a language.

“We can still catch them early enough and enhance the utility of learning another language, and hopefully we can give them the skills they will take with them when they graduate,” she said. “By keeping language instruction at Harvard at a very high level, we are giving them this idea that this is important.”

Preserver of antiquity

Another important aspect of linguistic study is Harvard’s role as preserver of antiquity.

Tucked behind an innocuous-looking door in Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology is the office of Marc Zender, who explores and speaks ancient and forgotten languages and teaches them to eager Harvard undergraduates.

Zender’s specialty is Classic Mayan hieroglyphic writing. Though the ancient classical Mayan language is no longer in use, there are 30 related, descendant languages still spoken. Through the study of those “close cousins,” with the help of historical linguistics, Zender said, researchers can reconstruct how the ancient language would have been structured and even how it sounded.

Helping students to appreciate language as a tool for understanding lets them “look over the shoulder of ancient scribes” and read what was important to cultures during their time, Zender said.

“The basic message is that language is our major vehicle for communication even today. Nothing has really replaced being able to either speak to other people or to write, which also so vividly captures a language and a culture.”

Last year, the lecturer on anthropology had more than 300 students in his elective “Digging Glyphs: Adventures in Decipherment.” The class, which attracts undergraduates from a range of concentrations, makes use of the collections in the Peabody and in Harvard’s Semitic Museum. Students attend weekly section meetings in the museums to explore the markings on pottery and tablets of ancient civilizations.

“They can literally touch the past,” said Zender, “and from a language direction, when something has writing on it and you can literally read it aloud, it makes the object come alive.”

Peter Machinist, Hancock Professor of Hebrew and Other Oriental Languages and an authority on the Hebrew Bible and ancient Mesopotamia, agrees that a key to understanding ancient societies is the careful study of language.

“Biblical thought and indeed the intellectual cultural traditions of most societies are communicated especially through languages,” said Machinist. “The choice and orchestration of words provide a clue to what the meaning of the world was about.”

But for Machinist, the study of language also offers students a window on today’s world.

“I’d like to think that the work that I and colleagues do, even if it deals with classical or even more remote antiquity, has a bearing on the contemporary scene, because at issue are traditions that are not dead,” he said, noting that the current Iran and Iraq disputes have echoes in those of ancient Persia and Mesopotamia.

“I am not suggesting that reading ancient texts is going to solve our problems in this region tomorrow, but it is going to give us a sense of whom we are talking to there, of what fundamental social, cultural, and ecological realities we are facing, which we ignore at our peril.”

The earlier requirement

Harvard College’s early language requirement was demanding and included three mandatory years of Hebrew, Greek, Aramaic, and Syriac. It was assumed that students entering Harvard had a full knowledge of Latin.

While today’s requirement is much less rigorous, and many undergraduates entering Harvard can test out of required language classes before they arrive on campus, many students choose to continue studying another language, taking advantage of the University’s vast resources to explore written and spoken words and cultures.

Currently, 154 Harvard students are concentrating in one of the University’s language concentration programs, which include East Asian Studies, Germanic Languages and Literatures, Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, Romance Languages and Literatures, Sanskrit and Indian Studies, and Slavic Languages and Literatures.

To further encourage students to continue their linguistic studies, the University adopted a language citation program in 1998 that recognizes advanced language learning at the College. The achievement is noted in students’ official transcripts, and students receive printed citations that recognize their accomplishments along with their diplomas.

In its first year, the program had 77 participants. Last year, 441 students received language citations. In 2006, FAS also established secondary fields as part of the curriculum. Undergraduates can now declare a secondary field of study in 46 areas, including nine language-based programs.

Languages and related programs also abound in Harvard’s other Schools. Harvard Law School has a class that teaches students Spanish language skills in a legal context. At the Harvard Business School, the student association recently began offering Berlitz Method language classes to first- and second-year students in Mandarin, Spanish, French, Portuguese, and Hindi.

In summer, the Harvard Divinity School offers language instruction geared to theological and religious studies, with courses such as elementary biblical Hebrew.

“Dead” language lives

Additionally, students regularly gather to speak at informal “language tables” hosted by the various Houses. For the past several years, a small but dedicated group of graduate and undergraduate students has met in an Italian restaurant to order pizza and chat, not in Italian, but in Latin. The students from Harvard’s Department of the Classics don’t let the fact that Latin is technically a “dead” language deter their enthusiasm.

“It’s hard to stop and think of the Latin for cell phone,” said junior Sara Mills, a classics concentrator and president of the Harvard Classical Club, which organizes the weekly event. The club has developed its own lexicon to translate modern terms such as “resident dean” or “Boylston Hall.”

The most amusing moments from the gatherings, which are sponsored by the department, often come in the form of a bemused waiter who tries to pick up their words, or from neighboring diners who whisper incredulously, “They can’t be speaking Latin.”

“We just smile, sheepishly,” said Mills.