DivaDiva II (2009) Station 28-DRR

File Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Deep thinking

Gonzalo Giribet nets rare invertebrate specimens from the seafloor

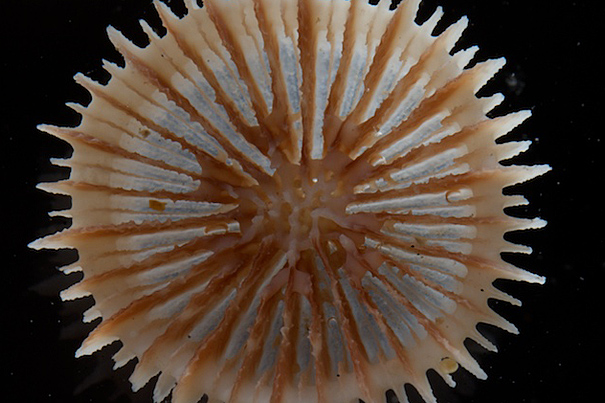

In the laboratory of biology professor Gonzalo Giribet, students and fellows are playing “getting to know you” with a haul of rare limpets, deep sea scallops, cold water corals, and ribbon worms.

The 100 or so specimens, gathered during a September cruise in the North Atlantic, will boost scientific knowledge of these mysterious creatures, some of which live 15,000 feet down, and bolster the Museum of Comparative Zoology’s invertebrate collections, of which Giribet is the faculty curator.

“There are not a lot of samples, but some of them are very precious because there are very few specimens known from these depths,” Giribet said.

Collecting is a key part of the work conducted in the Giribet’s lab, which focuses on the world’s invertebrates, which generally get less attention than better-known mammals, birds, fish, and reptiles.

Giribet’s work focuses on the world of crustaceans, insects, snails, corals, and arachnids. He and his fellows and students travel the world sifting leaf litter and diving among reefs to expand knowledge of these little-known creatures. His lab studies invertebrates not only to learn more about their biology, but also about the locales in which they evolved. Noting similarities and differences between related species in different parts of the world, Giribet seeks to shed light on the planet’s geographical history.

By visiting locations that scientists believe were once joined in the supercontinent of Gondwana — which contained many of today’s Southern Hemisphere landmasses — and examining creatures on either side of the rifts that eventually formed, Giribet can test those theories. Closely related creatures in eastern South America and West Africa, for example, would indicate they came from shared ancestor species.

Just last summer, Giribet and some lab members traveled to West Africa to collect velvet worms in Cameroon and Gabon. With only one species of velvet worm there, Giribet said, it was important to collect samples to compare with velvet worms on Caribbean islands and in Central and South America.

Other recent trips took researchers to New Zealand and Fiji. Trips to the Amazon and the Philippines are planned for the coming months.

September’s North Atlantic scientific cruise provided samples from a little-known but biologically important area, the Galicia Bank off Spain. Giribet was one of several scientists invited to participate by the University of Santiago de Compostela, which organized the trip.

The Galicia Bank features a seamount that rises from 15,000 feet deep to within 3,000 feet of the surface. It’s an area of enormous biological productivity and diversity, fed by upwelling waters that bring nutrients to the surface and feed a productive fishery. The area, proposed as a marine protected area by the World Wildlife Fund, is a day’s cruise from shore, Giribet said.

“It’s a really amazing area,” Giribet said. “There’s a huge diversity of cold water, deep sea corals.”

During 15 days at sea, researchers tested several collecting devices, including a benthic sledge, dragged along the seabed and then hauled back onto the ship. In water that deep, Giribet said, roughly six miles of wire had to be deployed before the sledge would reach the ocean bed, an operation that took three or four hours. They’d drag it for an hour and then haul it back aboard.

“One operation at the deepest depths takes eight or nine hours. Then you have to process the samples,” Giribet said.

With so much effort required for such a small time on the seafloor, the ship’s research ran around the clock, with the 60 people aboard divided into three teams on six-hour watches to keep the equipment running.

“The worst was doing the night shift,” Giribet said.

In addition to collecting specimens, Giribet said he was eager to see the ship in operation. Though he’d been collecting around the world for years, he hadn’t participated in deep oceanic collecting, with the important considerations of enormous pressures on top of logistical and scientific issues that would apply to other types of trips.

Collecting is an important activity not just for scientists in Giribet’s lab, but also for his students. Work in the field can be an energizing experience, Giribet said, and allows students to put classroom knowledge into practice during scientific activities. Giribet organizes a collecting trip each year over spring break for students in his class called “Biology and Evolution of Invertebrate Animals.” Students spend a week exploring and collecting on Caribbean reefs.

Each collecting trip requires far more lab time than field time to process, examine, and document the finds. Work in the Giribet lab on the North Atlantic specimens continues today. It involves taking DNA samples, photographing, dissecting, and describing the samples.

“For us, it’s very important to collect,” Giribet said. “You can only work on these things if you go to these places.”