Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

Havana, then and now

Exhibit shows historic postcard images, digital photo matches

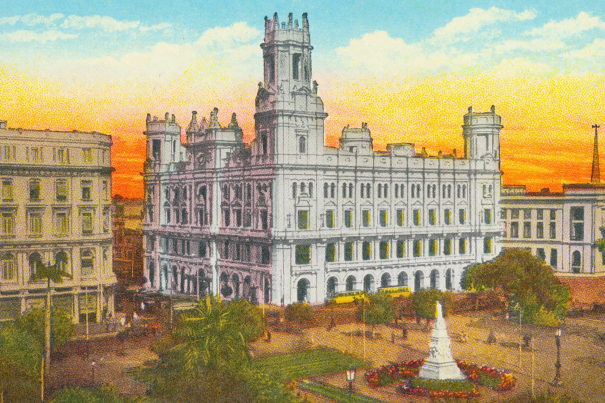

The pictures are hauntingly static. In a series of modern photos matched against century-old postcards, Havana’s sprawling boulevards, public squares, and majestic hotels appear side by side, frozen in time.

With the Cuban revolution in 1959, most development on the island nation, including construction, came to an abrupt halt. The result is a city landscape rich with historic structures (those that have not crumbled), standing as they were close to 100 years ago, largely unhindered by progress or overshadowed by steel and concrete towers. Spanish, Moorish, Italian, Greek, and Roman influences can all be found in Havana’s architecture, which covers periods from colonial and baroque to art nouveau and art deco.

The starring role in Cathryn Griffith’s photographs are the once-grand buildings and urban environments that are now undergoing a grand revival. To emphasize the sense of structural stasis, Griffith paired her current photos with postcard images from long ago.

A selection of her work, captured in her new book “Havana Revisited: An Architectural Heritage,” is currently on view at Harvard’s David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies. Located on the second floor of Harvard’s Center for Government and International Studies’ south building, 25 photos in the exhibit are paired with historic shots of the same site. Each frame challenges the viewer to discern significant change.

In one photo, an angular old corner building has been carefully cleaned and restored. It looks identical to the postcard image from 90 years before, with the exception of a tall building that looms just to its left. In another, a plaza with a church is instantly recognizable, even though the horses and carriages of the postcard image are long vanished. In their stead stand a bride and groom. In the foreground of another postcard image, a lush park surrounds the elegant capitol building. In the photo below, the capitol remains pristine, but the park has been replaced with pavement.

For Griffith, an artist and photographer, the inspiration began on a trip to Havana in 2003, when she was struck by the city’s rich architectural heritage. Visiting Paris afterward, she bought several historic postcards that captured Havana’s grand colonial structures in hand-drawn images and vivid colors from long ago. With the help of eBay, Griffith was able to amass a collection of more than 600 similar cards.

Ultimately, she found herself in the office of Leland Cott of Harvard’s Graduate School of Design (GSD), looking for guidance on her idea of uniting the past and present.

Cott understood Griffith’s desire to combine the images she had found with the photos she had taken in book form and helped her to conceptualize the project. Cott, a GSD adjunct professor in the Department of Urban Planning and Design who has taught in Havana, also connected her with his contacts.

Griffith made a dozen more trips to Cuba, searching for vantage points that matched some of her postcards, and taking digital photographs.

“Just think about what that means in terms of that city, that you can still do that,” Cott told a crowd gathered on Feb. 3 for an opening reception.

The almost imperceptible changes in the buildings, he said, were the result of two actions: a concentrated and well-designed campaign by government officials to restore historic structures to boost tourism, and what he called “benign neglect,” given the country’s dearth of material resources.

“Doing nothing in this particular case,” Cott said, “may have proven to be the most valuable preservation act of all.”

While Cott helped put Griffith in touch with his contacts, her most important connection was to a young Cuban man who became her tour guide and translator. Together, with his limited English and her broken Spanish, they snaked through the city, stopping strangers on streets, ringing random doorbells, and persuading hotel security guards to let them in so they could seek vantage points matching the postcards.

“The preservation of old Havana emphasizes the restoration of buildings to their old appearance,” Griffith said, noting that the effort is “not about change; it’s really about preserving or returning to an earlier state.”

Griffith added that the underlying philosophy of the restoration, according to Cuban officials, “is that it’s necessary to have an understanding of the past in order to successfully engage with the future.”

The exhibit continues through June 1.