Historical society, HU Press join forces to digitize Adams papers

Chennai, a city of 7 million, is the Detroit of South Asia, the hub of India’s automobile industry.

The centuries-old port city is also the center of a global “text conversion” industry, where printed books in English are retyped and encoded for digital editions.

Digitization converts heavy tomes into nimble electronic files that stream easily over the Internet, and are searchable with a few key strokes. It’s an appealing idea to a new generation of readers and scholars.

But the faraway venue for English text conversion in Chennai, with its millennium of economic history and its present-day simmer of Tamil politics, sets the stage for some jarring cultural interplay.

One example involves Boston. Workers at codeMantra in Chennai are now busily converting 45 printed volumes of early American documents published by Harvard University Press (HUP) and the Massachusetts Historical Society (MHS).

With the Bay of Bengal in sight, they’re retyping 18th-century letters from the Adams family, which begot two American presidents. And they’re keying in diary entries written almost 400 years ago by John Winthrop, the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

For both Harvard and the historical society, the joint digitization project is the first large-scale venture of its kind.

HUP, the publisher of 9,000 books since 1913, has given Google and Amazon.com permission to digitize portions of some of its titles. But the collaboration with the MHS marks the first time Harvard has had a “co-publisher” on such a large-scale, technically sophisticated project, said HUP director William Sisler.

For the MHS, which published its first book in 1792, the collaboration marks the first time any of its document-based books will be prepared for electronic editions.

The digitization venture, which MHS calls its Founding Families Project, was made possible because of a $300,000 grant awarded in 2005 by the National Endowment for the Humanities.

The MHS will match that amount with staff salaries over three years. Harvard will pay for the text conversion and for proofreaders to verify the accuracy of the transcription for the final online text.

HUP has no expectation of recovering costs, said Sisler. “We’re delighted to bring these seminal documents to the electronic environment.”

At the MHS, preparatory work on the electronic edition project started in July 2005. Text conversion in Chennai began this April and will end this fall.

By the end of June 2008, electronic editions will be posted on the society’s Web site (http://www.masshist.org).

Online will be 38 volumes of the Adams Papers, six volumes of the Winthrop Papers (five of them rare), and the one-volume “The Journal of John Winthrop, 1630-1649.”

The digitization project modernizes and expands a longtime partnership between Harvard and the MHS regarding the Adams papers. Traditionally, scholars from the historical society have transcribed documents, then compiled and annotated them for publication. Harvard then produced and distributed the books.

MHS scholars are still at work on unpublished Adams family papers, which will eventually be enshrined in books.

But across the hallway, technicians and editors are busy working to put the old books into a new, electronic format. They’re verifying encoding, creating a cumulative index, and tweaking the MHS Web site so users can easily access and search the historic documents.

Online editions of the Adams and Winthrop volumes will be faithful electronic reproductions of the published books. That includes 80 years of scholarly indexes, footnotes, and annotations.

Digitizing books jammed with scholarship is a big job. Each volume contains an average of 300 letters, diary entries, or other source documents.

But once finished, the digitized, searchable editions will be “better than pulling books off shelves,” said Ondine Le Blanc, associate editor of publications at the MHS.

Digitizing scholarly books is not simple. Just scanning the printed pages of each book won’t do. Not accurate enough, said Le Blanc, and scanning alone would not make the text searchable.

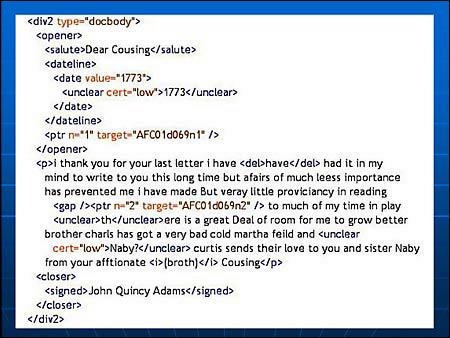

So each page of the 45 volumes must be “keyed.” That means retyping every word, as well as typing in embedded codes. The codes resemble the markup language an editor might use for print editions. They bracket salutations, signatures, footnotes, indexes, timelines, and other discrete textual items. Often, a single line of original text, when digitized, will be surrounded by five or 10 lines of code.

Publishing online editions of scholarly books is still new, said Le Blanc, and strategies are still emerging. They were a topic of discussion in Quincy, Mass., last month, at the annual meeting of the Association for Documentary Editing (Oct. 20-22).

Electronic editions of existing scholarly books require a new layer of technical sophistication, but will provide scholars and readers with “an online learning environment,” said panelist Kenneth Minkema of Yale University.

The Jonathan Edwards Center at Yale Divinity School is publishing a 26-volume online edition of the 18th century preacher/theologian’s sermons, letters, and treatises.

Mark Saunders, an editor at the University of Virginia’s electronic imprint, Rotunda, said digitizing printed books requires “a kind of second typesetting.”

The computer coding makes intermediate pages look complicated, he said. “It isn’t humanly readable. But the computer loves it.”

(Virginia’s Founding Era collection of digitized documents will include the Adams papers being prepared in Boston for electronic publication.)

Because encoding is so complex, MHS sends codeMantra only eight volumes of the HUP books at a time, with detailed instructions.

Despite controls, said Le Blanc, “what you get back is a fixer-upper.” In Boston, the coding is checked and enhanced. Every correction is logged.

But the final accuracy of the electronic editions will depend on hardworking, detail-oriented proofreaders. They pore over the digital version, comparing it – word by word – to the printed original. “In terms of quality assurance, that’s huge,” said Le Blanc.

Harvard’s financial commitment to the digitization project, along with the federal grant and the collaboration with MHS, assures that the online Adams/Winthrop editions will be available free.

It’s not a luxury the University of Virginia projects have. “We have to think about how to sell this stuff,” said Saunders. The Rotunda imprint offers a subscription model of pricing, and special rates for university and library users.

At Yale, the online Edwards collection charges for its searchable sermons and treatises of the revivalist pastor who gave the world “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.”

But the Yale site also resorts to broader ways to make money. The Edwards Web page, for one, offers “the long-awaited T-shirt.” It reads: “Jonathan Edwards is my Homeboy.”

Other problems with digitizing scholarly books are more mundane than funding. Like search-engine optimization for documents protected by computer firewalls. Saunders complained that searches for “Dolly Madison” turned up more hits for snack cakes than for the historical figure.

Spelling variants – rife in old documents – present search engine problems too, said Le Blanc.

Images in digital editions can also present legal difficulties. Rights to text and pictures are often in different hands.

And contract language for digital editions of printed books may need work. Yale University Press first asked the Edwards project for 50 percent royalties – and movie rights. (The problem was resolved.)

But despite start-up bumps, digitization is an exciting prospect for publishing houses that want their book-bound scholarship to go beyond print, into the world of the Internet.

“It makes the things we collect all the more accessible, which is very exciting,” said Le Blanc. “People are going to be able to access this from all over the world.”