Harvard takes first Allston steps, refines master plans

A year of planning publicly

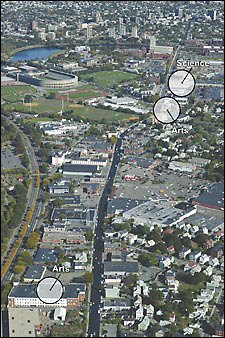

The University’s plans for a 21st century extension of its campus in Allston took more definite shape this year with the selection of a site and architect for a half-million-square-foot science complex, as well as the announcement of plans for new arts and culture facilities.

These first steps, taken after three years of extensive planning and consultation within the University, with the city of Boston, and with the surrounding communities, are the beginning of a multi-decade process to imagine and build in Allston the educational, research, and residential facilities necessary for Harvard to advance knowledge and maintain academic leadership into the next century.

“It’s very encouraging to see that plans for Harvard’s properties in Allston, while still in the early stages, have become much more tangible in recent months. Sites have been identified for a new science complex as well as interim arts and culture spaces, and we anticipate additional forward movement in the months ahead,” said Jamie Houghton, senior fellow of the Harvard Corporation. “Our ultimate goal in Allston is to strengthen Harvard’s long-term capacity to generate exciting new knowledge and ideas and to educate the very best students of each generation. The progress we have made this year brings us appreciably closer to that goal, and I’m grateful to all those who have played a part.”

• Faculty task force makes University science recommendations

• Allston Progress report of faculty task forces 2004

• More information on the Harvard in Allston Exhibit Room

• More information on Allston planning

Also in this issue:

• Stefan Behnisch explores Harvard’s architectural past and present, and considers the future

In addition to announcing its first projects this year, Harvard established a public display to share preliminary ideas for Harvard’s future in Allston; held forums to solicit feedback and discuss concerns of faculty, students, staff, alumni, and Allston residents; and created the Allston Development Group to oversee planning for, and ultimately the building of this new dimension of Harvard’s campus.

Christopher M. Gordon, chief operating officer of the Allston Development Group and former director of the $4.4 billion Logan Modernization Project for the Massachusetts Port Authority, describes the accomplishments of 2005-06 as having established a foundation for Harvard’s future in Allston.

“When I arrived at Harvard, I discovered a solid foundation of planning for the Allston Initiative,” said Gordon. “President Summers’ vision and leadership and the thoughtful input we’ve received from the Harvard and Allston communities have made it possible for the University to begin to realize ideas that have evolved over nearly a decade.”

Over the coming year, the University will refine its thinking about the programmatic elements of the extended campus with a goal of developing a comprehensive, yet flexible, 50-year master plan for Allston. According to Gordon, Harvard’s planning team expects to complete the plan – a framework with future building locations, street and block patterns, new open spaces, better riverfront access, and transportation improvements – in the next year with additional input from all corners of the University community and beyond.

Said incoming interim President Derek Bok, “The year ahead promises to be one of progress as the University’s planners, in consultation with the Harvard community and our neighbors, continue their efforts to help shape and strengthen Harvard for decades to come.”

A year of planning publicly

Recognizing the importance of broad consultation, leaders of the Allston planning process have made a point of soliciting input from a wide range of groups. To that end, the University opened the “Harvard in Allston” exhibit room in the Holyoke Center arcade in October 2005. The Allston Room, as the exhibit has become known, displays preliminary ideas and possibilities for Harvard in Allston identified by Harvard’s planning consultants, the Cooper, Roberston, Gehry, Olin collaboration – ideas being considered as part of Harvard’s 50-year Allston master plan. The exhibit has drawn more than 2,000 visitors, including members of the Harvard community and residents of the city of Boston and surrounding neighborhoods.

Harvard’s planning team also solicited the ideas and opinions of Allston residents and Harvard faculty, staff, students, and alumni through a variety of other forums.

The President’s Advisory Committee on the Allston Initiative, a group of Harvard alumni and friends led by Robert M. Bass and Penny S. Pritzker (A.B. ’81) – many of whom are experts in urban planning, design, and development – met regularly this year to advise the president and the Allston Development Group on planning.

At a workshop run by Project for Public Spaces, a nonprofit organization dedicated to creating and sustaining public places, 50 Allston residents discussed ways the surrounding community could benefit from a future campus and proposed ideas like outdoor meeting places, parks, play areas, fountains, cafes, restaurants, and possibly a farmers’ market. Harvard and the Allston community task force appointed by the mayor in December 2005 are also meeting regularly to discuss these and other ideas.

“The feedback we have received and will continue to solicit is a critical part of the iterative process of planning,” said Kathy Spiegelman, chief planner for the Allston Initiative. “These comments are helping us sharpen ideas, identify key issues, and, ultimately, will help us realize a successful long-term vision for Harvard in Allston that will serve generations.”

Science, culture emerge as first projects

As thinking about Harvard’s future in Allston progressed, science and the need for facilities to accommodate new ways of approaching scientific research and exploration emerged as a University priority.

“When considering the history of our scientific enterprise – of any scientific enterprise – what quickly becomes clear is the difficulty of predicting, and preparing for, future needs,” said Harvard Provost Steven E. Hyman. “There is simply no more room left in Cambridge for the long-term growth of interdisciplinary science,” he said, “so if we are to grow, and we must, and remain nimble, it will have to be in Allston.”

Hyman pointed out that fields of science change over time, and noted that facilities have to be flexible. “We need to design facilities that can accommodate changing needs, that can be used for one form of investigation for a period of years, and then can be adapted for another use,” he said.

Last winter, at the request of Harvard’s science deans, Harvard President Lawrence H. Summers appointed a broadly based Science Planning Committee, including representatives of science departments and Schools across the University, to build on the long-range Allston science planning done by Harvard faculty to date.

“The important thing is that this is an effort to ensure that Harvard will be the best place in the world to do science,” said Andrew Murray, Herchel Smith Professor of Molecular Genetics, director of the Bauer Center for Genomics Research, and one of the co-chairs of the committee. “And it’s an effort to do that by broadly representing the faculty in eliciting good ideas about areas to grow science and engineering over the next 10 to 20 to 30 years. Larry Summers said he wanted us to have an impact so that his successor’s successor would be grateful to us.”

“Science is going to be distributed across the North Yard in Cambridge, Allston, and Longwood; the idea is to get as much input from people and weld it into a coherent plan,” Murray continued.

Douglas Melton, co-director of the Harvard Stem Cell Institute, the Thomas Dudley Cabot Professor of the Natural Sciences, and Science Planning Committee member, said, “When changes occur in science, they do so more rapidly than in other disciplines. The University needs to plan for the scientific future in a way that allows it to be as nimble as possible. Any plan for the future of Allston science must be integrated with planning for science on what will be the University’s three centers of science.”

Harvard is committed to sustainable planning, green building design and sustainable campus operations, such as running its entire diesel fleet with biodiesel. Head Mechanic Mark Gentile fills up on of Harvard’s busses at Harvard’s bio-diesel filling station in Allston. (Staff file photo Rose Lincoln/Harvard News Office)

Harvard is committed to sustainable planning, green building design and sustainable campus operations, such as running its entire diesel fleet with biodiesel. Head Mechanic Mark Gentile fills up on of Harvard’s busses at Harvard’s bio-diesel filling station in Allston. (Staff file photo Rose Lincoln/Harvard News Office)

The need to foster that integration – and the pressing need for a home for the Harvard Stem Cell Institute, where scientists can work side by side sharing findings and approaches that may apply to different organ systems – led to the University’s first Allston projects, announced in February. At that time, Harvard selected the architectural firm Behnisch Architekten of Stuttgart, Germany, to design a state-of-the-art science complex in Allston, south of Western Avenue near the Harvard Business School.

The announcement was embraced by the mayor of Boston. “The construction of this 21st century campus in Boston will have a positive transforming effect upon the Allston neighborhood and the city, strengthening the position of Boston as the life sciences capital of the world and increasing the capacity of our economic engine,” said Mayor Thomas M. Menino.

Arts and culture to enliven Harvard in Allston

At the time of the science announcement, Harvard also unveiled plans for interim arts and cultural spaces to be created in Allston, including a new visual arts center on Soldiers Field Road. Menino noted that the coming arts and culture facilities would “not only enrich and inspire students and faculty, but also neighborhood residents as well.”

In May 2006, the Harvard University Art Museums announced the selection of Daly Genik Architects of Los Angeles to design the visual arts center. The center, which would enable the renovation of the Art Museums’ facilities in Cambridge and serve Harvard students and the public, marked just the beginning of the University’s arts and culture presence in Allston.

Charting the course for arts and culture in Allston was the mission of a committee of arts and culture faculty, museum directors, and arts leaders convened in the fall. The committee met throughout the year to consider Harvard’s needs as well as what would be required to make Allston a culturally vital campus for students, faculty, and neighbors. In the coming year, the group will engage additional faculty members and other constituencies in discussions to further refine Allston arts and culture plans.

“The Arts and Culture Steering Committee has been a marvelous forum for imagining communities, both for Harvard and for Allston and the greater Boston area. While most of us have thought of our respective pursuits in terms of the academic and extracurricular needs of our own students and faculty, it is inspiring to think of ways in which Harvard can share what it knows and does about culture and the arts of the world with the larger community,” said William Fash, Bowditch Professor of Central American and Mexican Archaeology and Ethnology, Howells Director of the Peabody Museum, and a member of the arts and culture task force.

“We have had fun and quite a few challenges envisioning the ways in which culture and the arts at Harvard can ‘act locally’ while thinking and working globally,” Fash added.

While science and arts and culture planning advanced this year, Harvard’s School of Public Health and the Harvard Graduate School of Education continued their own academic planning and assessment of the opportunities and challenges offered by a prospective relocation to Allston.

One school already in Allston welcomes the presence of new academic neighbors. “Harvard’s expanded presence in Allston is an extraordinary opportunity for the University in general and for the Business School in particular,” said Jay O. Light, dean of Harvard Business School (HBS). “One of my goals as the new dean of HBS, after more than 30 years on its faculty, is to increase the amount of collaboration between the Business School and the other professional schools. Thanks to the leadership of President Summers, Allston will become a center for world-class research and development in biotechnology, as well as the home of various Harvard professional schools. These are exciting developments in the history of the University, and I am eager to do all I can to make them a great success.”

A successful crossroads for campus and community in Allston

Gordon said the issue that came to the surface most clearly during the year’s consultation was the look and feel of a future campus. “Harvard faces the challenge of respecting and building on its traditions, while remaining open to design innovation in the new century,” said Gordon. “We know Allston is not going to be a replica of Harvard Yard in Cambridge, however, it has to be equally iconic – a successful common ground for Harvard in the 21st century – and we are working to understand what that means.”

In selecting Behnisch Architekten, a design firm known for its leadership in environmentally sustainable design, for Harvard’s science complex in Allston, the University made a conscious decision to emphasize principles of sustainability at the outset of planning for the new campus, beginning with its first project. Stefan Behnisch, as the project’s lead, signals increased expertise in the area of sustainable development and green building design.

Ultimately, what happens in Allston will be exceptional and open to all, says Laurie Olin, principal of Olin Partnership and professor of landscape architecture and regional planning at the University of Pennsylvania. “One thing about great universities is they have a tradition of providing high-quality public space that is desirable to the university community, the neighborhood, and society at large,” said Olin. “Harvard understands the importance of creating a campus with a generous public realm that is handsome, well built, environmentally sustainable, and attractive and will give the community an identity.”

“We can create a place that is open, free, and usable by all people – families and children, and faculty, staff, and students – and contributes to the quality of life of the Allston community and Boston region,” Olin added.

Progress to come

In the coming year, The Allston Development Group will assist Harvard’s project planning committees to complete designs for the science complex and the visual arts center, and will begin building both projects. Meanwhile the consultation process will continue through the use of the Allston Room and other forums. Harvard’s planning team expects the preliminary vision for the first full phase of development for Harvard in Allston to become more refined within the next year.

That vision includes the further enhancement of Harvard science and research; the strengthening of the University’s professional schools through the increased collaboration and intellectual integration resulting from the relocation of the School of Public Health and Harvard Graduate School of Education; the identification of arts and cultural activities that would enliven a campus; housing for undergraduates along the Charles River; housing for graduate students and community residents; and ways to seamlessly integrate Harvard in Allston, Harvard in Cambridge, the Longwood Medical area, and beyond.

“The next steps of the master planning process have to be carefully considered,” said Gordon. “The University has done a lot of thinking about what makes sense, what might fit. We need to refine these ideas and think about how to make the master plan really come alive – what will the new Harvard look like? How can we make it a wonderful, livable place? Where will things be? When will they be built? – these are all key questions to explore further in conversations with people in the coming year.”