Rediscovering Roxbury’s revolutionary role

Extension School students delve into primary-source materials to unearth stories of the Siege of Boston

In April 1775, minutemen and patriot troops began pouring into the Boston area to surround the British army and contain it in the city. In April 2006, Harvard Extension School students are poring over centuries-old documents to advance our knowledge of what has become known as the Siege of Boston.

The students are volunteers from Robert Allison’s Extension School course HIST-E-1632, “The History of Boston.” Allison’s fledgling historians are looking at documents, including diaries, ledgers, and journals, to try to get a sense of what life was like during the Revolutionary War.

“It’s a terrific opportunity for the students,” said Allison, who is also a professor and chair of the history department at Suffolk University. “It gives them a chance to work with primary source materials and find out how much fun it is to be able to discover history on your own.”

One of Allison’s students, Lauretta Woods, enthuses about her opportunity to do this research: “As an undergraduate,” she said, “I never expected to have access to primary sources. For me, it’s a great and rare opportunity. It also gives some texture to the lectures and the texts that we read. … I have a much broader picture now of this period.”

The students are focusing on materials that relate to the patriot army that was encamped in Roxbury. At the time of the war, Boston was located on the Shawmut Peninsula, before massive landfills in the 19th century filled in adjacent waterways. The town closest to the “Boston neck,” the only land route to Boston, was Roxbury. It was the troops in Roxbury who stopped the British from simply walking away.

“We’ve memorialized Lexington and Concord,” said Allison, “but Roxbury is part of the broader story and it’s an essential part of the Revolutionary War story.”

The story is that in April 1775, the British seized patriot gunpowder at Lexington and Concord, essentially beginning the war for independence. The British were then driven back to Boston by the minutemen. An alarm from Lexington spread throughout eastern Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, and New Hampshire and brought thousands of Revolutionary troops to surround the British. Gen. George Washington set up camp in Cambridge, and Gen. John Thomas set up camp in Roxbury. The patriot troops kept the British contained in Boston until March 1776, when the patriots fortified Dorchester Heights with cannon sent from Fort Ticonderoga in New York. Faced with the overwhelming threat of the cannon, the British boarded ships and sailed away from Boston. This event is commemorated each year in Boston on March 17 as Evacuation Day.

“The work the students are doing here is essential to understanding the whole story. They’re finding things out that historians don’t know and they’ll be able to tell the story of the siege of Boston and bring new life to the story, finding out who these people were, what brought them here, and what Roxbury was like during this period,” said Allison.

Pork, bread, and beer

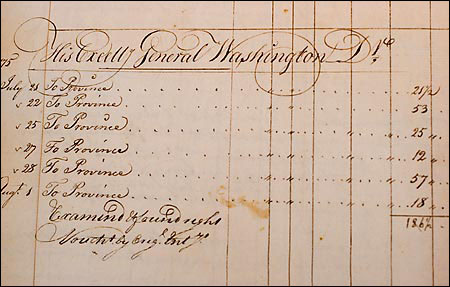

Woods is working with the official commissary ledger for the Massachusetts army as kept by John Pigeon. One goal of Woods’ research is that by identifying the quantity of supplies given to various commanders and regiments, we can infer the approximate size of the companies. The official business contained in the ledger covers the distribution of foodstuffs, which Woods has discovered consisted mainly of pork, bread, and beer.

To her surprise, Pigeon has turned out to be a lively character, mixing his personal writings in with his ledger. Woods has discovered Bible stories, poetry, musical scores, and personal letters within the pages of the ledger. “It gives us a glimpse beyond his duties as commissar to him as a person so that we’re able to see a rather colorful character,” said Woods.

Andy Lobb is reading the journal of John Kettell. Lobb, who lives in Newburyport, was excited to find that Kettell begins his story in that city. According to Lobb, Kettell “categorizes religiously every day – he says what day it is, what date it is, what the weather is, and generally concludes with a hearty ‘all is well.’” Only on days with an unusual event does he write something more: Unusual events include cannon shots, house fires, and deserters coming across from the British line – and military punishments. “He does have a penchant for talking about military punishments that are occurring,” said Lobb. “He talks about rogues being whipped and he counts the numbers of rogues being whipped or forced to ride a wooden horse, a form of torture. … He also talks about soldiers who go into pillories. These appear to have made a large impression on him.”

Both Woods and Lobb say that it’s been challenging trying to glean pertinent information from their materials. They mention faded writing, idiosyncratic penmanship, and archaic spelling as obstacles to understanding. Still, they press on. Lobb likens himself to a detective, putting together the pieces, and Woods is enjoying herself so much that she has volunteered to extend her research into next summer.

The work is being carried out in cooperation with the National Park Service and Discover Roxbury, a nonprofit organization that celebrates Roxbury’s arts, history, and culture. With a joint civic engagement grant, the two partners are working to develop a Roxbury-centered Revolutionary War tour. They held a brainstorming meeting in December 2005, during which they identified gaps in their knowledge and unexplored historical resources kept by the Massachusetts Historical Society and the Boston Public Library. Allison, who was at the meeting, said that he would ask his Harvard students if they were interested in investigating these resources. Thirteen students have volunteered.

Sheila Cooke-Kayser, education secialist at the National Park Service said, “This is great for us because those students are doing work that would take years and years for park rangers to do. … This is a fabulous help for us.”

Marcia Butman, director of Discover Roxbury, thinks it’s important work because “Roxbury’s history hasn’t really been told and it’s an important part of Boston’s Revolutionary War history – it’s like a missing link.”