Russian, U.S. admirals talk to save sub

KSG Executive Program forged ties that saved lives

Six hundred feet below the Pacific Ocean surface last August, seven Russian sailors sat trapped in a small, cold submarine hoping it wouldn’t become their collective coffin.

They moved as little as possible to conserve energy and oxygen, shutting off heaters and other nonessential equipment, surviving on a few handfuls of water each day as Russian authorities above scrambled in a desperate race to reach them before air ran out.

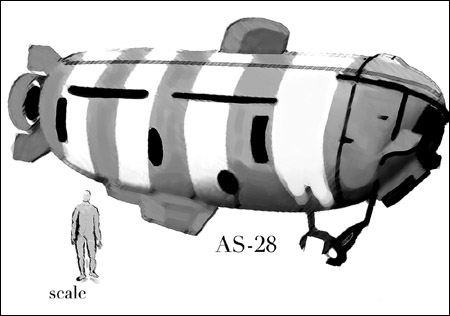

Efforts to raise the sub with slings and to drag it to shallower water failed, as the AS-28, a mini-sub itself designed for undersea rescue, remained tangled in fishing nets. Aghast, the world watched the drama unfold, fearful that the Kursk tragedy of five years earlier was replaying before its eyes.

The Russian nuclear submarine Kursk sank to the bottom after an explosion tore a hole in its hull. Russian rescue efforts failed and all 118 on board were lost.

As the AS-28 situation became increasingly desperate, a Russian admiral picked up the phone and called a friend thousands of miles away at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow.

The phone call, between two men who met at the John F. Kennedy School of Government’s U.S.-Russia Security Program in 2004, began a chain of events that resulted in U.S. and British equipment rushing to the scene and a British undersea rescue vehicle ultimately freeing the AS-28 and saving the sailors’ lives.

Kennedy School officials said the incident illustrates the importance of programs that bring together diverse participants from many countries, who not only learn from each other, but who forge a network of informal relationships that can be called upon in times of need.

The phone call between Russian Adm. Vladimir Avdoshin and the U.S. Embassy’s defense attaché, Rear Adm. Ben Wachendorf, was against Russian government rules prohibiting direct contact between members of the Russian military and those of another country. But in the AS-28 emergency, with lives on the line and the clock ticking, Avdoshin decided to bend those rules and call his friend from Harvard.

“He called and said, ‘I am calling you as a military officer and a friend as well. We need help, what should we do?’” said Sergei Konoplyov, the U.S.-Russia Security Program director.

Konoplyov, who recounted the story last week with the blessing of both Avdoshin and Wachendorf, said that Wachendorf said he would pass the request to his own superiors but recommended that Avdoshin also call the British defense attaché with the same request.

The result was that the U.S. and British both rushed remotely operated underwater rescue vehicles to the scene, off Russia’s Kamchatka peninsula. The unmanned British Scorpio 45 ultimately cut the steel cables that held the sub down. After 76 hours, with just 12 hours of air remaining, the sub surfaced and crewmembers were able to climb out on their own.

Konoplyov said officials of the U.S.-Russia Security Program heard the story last month at the annual U.S.-Russia Security Workshop in Moscow, when a U.S. admiral offered a toast to Avdoshin’s courage. Col. Gen. Valeri Manilov, adviser to the speaker of the Upper Chamber of the Russian Duma, who was present and who had participated in the program in 1991, said the incident made the investment of time and money in the program worthwhile.

Konoplyov said the AS-28 incident is one example of the importance of forging understanding and personal ties between the two nations and said no one knows how many other similar contacts have had positive effects.

“This story is just a major highlight of what can happen with the program. We don’t know how many other stories we’re unaware of,” Konoplyov said.

The U.S.-Russia Security Program, supported by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and in its 15th year, brings together a small group of top-level military and foreign affairs officers from the United States and Russia for a week at the Kennedy School. Classes, offered once a year in both Cambridge and in Moscow, include security-related issues important to both nations. In 2003, classes were presented on India and Pakistan, nuclear terrorism, the media and the military, NATO, central Asia, post-Cold War U.S. strategy, and a variety of other topics.

Konoplyov said the program doesn’t aim to “brainwash” the Russian officers, but rather offers a neutral environment where they can hear presentations and have frank discussions. These are people who are doing similar jobs, who are in different parts of the world, operating in different cultural, economic, and other circumstances, he said.

“It gives an opportunity to do some bonding and to let people who, even if they don’t become friends, at least be acquaintances,” Konoplyov said. “They sit together in classes and work together.”

For the Russian participants, the week at Cambridge is the program’s second week. The first week after they leave Russia, they spend time at NATO headquarters in Brussels and with British military officials in London. Konoplyov said he encourages them to ask the same questions in both Europe and the United States and assures them they’ll get different answers.

At the end of the program, each participant receives a list of contact information for the other participants, including telephone numbers and e-mail addresses. Such information can be invaluable when a crisis emerges. In addition, the wide recognition of the Harvard name can replace long explanations to superiors and peers when a former participant explains the contact simply: “This is my Harvard buddy,” Konoplyov said.

In this case, a phone call made possible by informal contacts forged a world away prevented a second submarine tragedy in five years.