Running in Lesotho

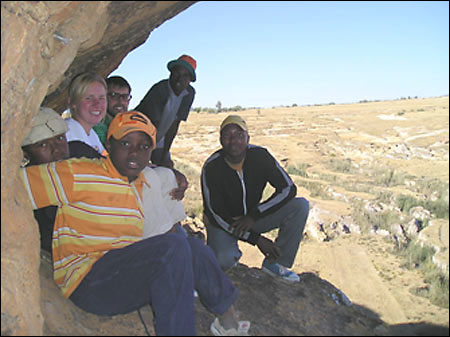

Editor’s note: Graduate student at the School of Public Health and resident tutor at Leverett House Jane Humphries ’03 spent her summer working in Lesotho, Africa, in the village of ha Ntlama, under the auspices of Operation Crossroads Africa. In addition to assisting in a local clinic, distributing medicines and vitamins, watching after children while their mothers visited doctors, and teaching at the local school, Humphries and her fellow volunteers worked hard on AIDS awareness in this area where many families are affected by HIV. She also took the occasional run.Mountainous Lesotho has the ‘highest lowest elevation of any country in the world.’During our first week in ha Ntlama, four of my fellow volunteers and I decided to go for a brief jog along the one road leading out of the village. Several obstacles made this more of a challenge than we had anticipated: The elevation and hills left us gasping for air, as Lesotho, Africa, is an entirely mountainous country with the “highest lowest elevation of any country in the world.” The dirt “road” was strewn with pebbles and large rocks that we had to navigate in uneven zigzags. And, most distracting of all, about 50 young Basotho children ran along beside, behind, and in front of us. As one jogger said, it felt like we were either the leading pack of runners in the Boston marathon (the cheering!) or the Beatles in “A Hard Day’s Night” (the chasing!).Village teenagers sing and dance at the welcoming ceremony for the OCA volunteers.I was in Lesotho with seven other Americans thanks to Operation Crossroads Africa, an organization founded in 1957 (and later a model for the Peace Corps). The organization sends volunteers to African nations to help with community development projects for two months during the summer (winter months in southern Africa). My group included five seniors in college (two from West Point, and one each from Fordham, Caltech, and the University of Washington), a photographer from Los Angeles, and an outdoor educator from Ohio who served as our group leader. As I struggled along in my Brooks running shoes, the kids pranced beside me in their bare feet, grinning widely. They were not the slightest bit winded, and were utterly unfazed by the rocks beneath their unprotected feet. I believe that they were smiling because they were amused – “Who are these five strange Americans? Why are they wearing shoes? And WHY are they running?” The concept of aerobic exercise does not exist in this remote village. Basotho villagers work their bodies all day long in order to survive.Children often run or walk barefoot along the one road that weaves through the cluster of villages.With no running water in their homes, the villagers’ activities center around nearby wells. Children play ball games as they wait in line for their turn to fill their buckets, and women bring their laundry to the wells for washing. Most people have to carry the heavy buckets and clothes back to their homes on their own, though some rely on their donkeys. In addition, many of the men spend their days harvesting in the fields or herding sheep through the mountains. Women tend after the children, cook, clean, and harvest the gardens. Teenagers are often sent to get food from the nearby store, a trip that could be as far as nine kilometers (about six miles) in some cases. With all the walking, playing, pumping, kneading laundry, and carrying heavy buckets, aerobics is not only a foreign term to these villagers but a foreign concept. It’s no wonder we were such a spectacle during that first jog!Shepherds in Lesotho wear wool for protection from the cold and wind. These men spend every day of their life herding sheep through the mountains.As I became more secure with my surroundings, I often went on my runs alone. I found that these wanderings taught me much about the Basotho people. And the land, too – jogging along, I surrendered myself to the beautiful landscape. The mountainsides were speckled with Basotho huts, cornfields, donkeys, cattle, and aloe plants (Lesotho’s national plant). Sadly, trees were sparse, and bald spots of stone were interspersed among the cornfields. The lack of trees has fed the soil erosion problem that Basotho farmers currently face.The Basotho people rely on subsistence agriculture for survival. Animals raised by Lesotho farmers include cattle, donkeys, chickens, pigs, dogs, and sheep.I quickly learned that it was considered rude for me to run past someone without stopping to talk. Basotho people put friendship and conversation above anything else. It is customary to stop and talk with someone in the road even if you end up 15 minutes late for an appointment. It’s quite beautiful. They are sincerely interested in each other’s lives.The Matlokotsi brothers, Thoriso (from left), Mokete, and Motlanyana, showed the volunteers around and taught them Sesotho words.So, my attempts at exercise became stilted journeys from one Basotho villager to the next. The questions “Where are you going?” and “Why are you running?” became more familiar to me than “lumela” (“hello” in Sesotho). Without fail, the Basotho people are very interested in everyone around them, including the random blond woman jogging through their village. Some of the villagers took the opportunity of our meeting to ask me for money or candy. If only I’d been able to give them the endless amounts of money that they assumed I had! One young man asked me if I could please get him a real job (many young Basotho men are presently unemployed). It was difficult to explain to him that I had no power to do so.OCA volunteer Christina Gambino and a young Basotho child watch a sunset.The younger children were drawn like magnets to my MP3 player – “Give me your radio!” I often stopped and let them listen to the music for a while. I watched in amazement as a group of five or six children considerately passed the headphones from one to the next, each getting a fair chance to listen. The Basotho children know to watch out for one another. The older ones hold the hands of the younger ones, caring for them and showing them what to do. Because many Basotho parents work all day and others are ill or have passed away from AIDS (one in three adults has HIV in Lesotho), the children have become each other’s caretakers. This camaraderie carries through to the high school and young adult age groups. Watching an agriculture class at the local high school, I noticed that the students were leaning on each other and intertwining arms in a manner that parents might do with their children in the United States. It was beautiful to observe such familial love among adolescent peers.A woman’s donkey and dog wait patiently as she collects water from a nearby spring.This support shone through again when I attended an HIV discussion at the high school with my fellow Operation Crossroads volunteers. The local HIV counselor, Matlotlo, had agreed to conduct two sessions on HIV – one about stigma and community support; and another about the biology, prevention, and testing of the disease. Despite their general openness with one another about most things, the stigma surrounding HIV in Lesotho is stifling. So, when the high school students were offered the option to get tested for the disease after the discussion, it was moving to see that 10 of them were willing to take the chance.Members of the Maseru Women’s Senior Citizen Association host a luncheon in honor of the OCA volunteers.As Matlotlo counseled each student individually, the waiting students were kind and supportive with one another. I can’t imagine what was going through their minds as they waited, but they had their virtual family right there with them. In the end, one of the 10 students turned out to be HIV positive, a ratio that is far better than the one-adult-in-three statistic. That student will get continued support and guidance from Matlotlo. During my last jog in ha Ntlama, I ran into one of the girls who chose to get tested. She stopped me, and with teary eyes, offered a heartfelt thank-you to me and the others for bringing the HIV counselor to their school. They had needed a venue in which they were allowed to talk about the disease. The rest of my run was much more inspired. Tsenolo of ha Ntlama poses proudly with her daughter. Right, even young Basotho children look after the infants of the village.I have many vivid pictures from those runs – two small boys jumping out from behind some cornstalks to scare me; herders climbing slowly up a hillside, patiently waiting for the cattle and sheep to graze; an unlikely herd of cows, donkeys, dogs, sheep, and horses crossing the road together in front of me; a cow running at me from behind!; a young girl who always climbed the one tree in her yard to wave.Victor and Boteng Hlalele were generous hosts of OCA volunteers on their ha Ntlama compound.My favorite memory from my jogs is of three young girls who were listening to my music and dancing along. They shrieked with glee as their bodies swayed to the beat. In general, Basotho people are very musical. They start singing at any moment, and they sing as though they could open up the skies. I witnessed old women with ailments and tired bones burst out into harmonious song and start dancing as though they were 20. I got to hear young men and women harmonize in unison at a local village ceremony. Walking by the primary school, one could hear the children singing together inside, and the church choir singers could have been professionals! During my entire stay in Lesotho, I felt as though the Basotho people could hear a resounding rhythm in the mountains that I could not detect. No matter how trying their circumstances or how extreme their losses were, their bodies seemed to reverberate with a beat that fed their souls. As the young girls passed my headphones back to me, one of them asked “Where are you going?” and another asked “Why are you running?” I tried to explain that running was good for my heart. And then I realized that the best thing I could do for my heart would be to embrace some of the contagious optimism that shone in their eyes, and to start dancing too.Young Basotho children wait for ceremonies to begin near the hut of ha Ntlama’s chief.The group’s official hosts in Lesotho were the women of MWSCA (Maseru Women’s Senior Citizen Association). But primarily, they were hosted by the Hlalele family, who watched over the volunteers. Humphries wants to acknowledge the family’s generous help: “There was a Hlalele looking out for us wherever we went!”