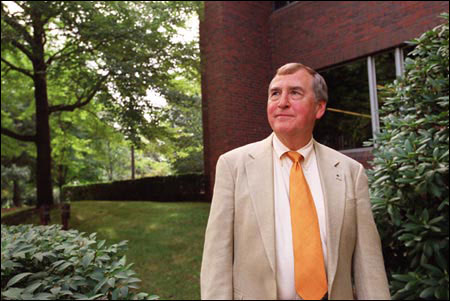

An interview with KSG’s Graham Allison

Professor, author talks about nuclear terror

Graham Allison, the Douglas Dillon Professor of Government and director of the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at the Kennedy School of Government, has published a new book titled “Nuclear Terrorism: The Ultimate Preventable Catastrophe.” Allison, an expert on arms control and defense policy, served as assistant secretary of defense for policy and plans under President Clinton. In a recent conversation, he discussed his ideas for preventing the all-too-likely possibility of terrorists setting off a nuclear bomb in a major American city.

You make such a powerful case in the first part of your book for the fact that a terrorist nuclear attack is possible that it made me wonder, why hasn’t it happened already? What’s holding them back?

Well it’s a great puzzle. My conclusion is, first and most importantly, that we’re living on borrowed time. The factors that would lead to the conclusion that this could happen, or even that it is likely to happen, are so clear that the fact that it hasn’t happened is something we should give thanks for. We’ve got a respite here to do things we should have done already.

But as the title of your book suggests, nuclear terrorism is a preventable catastrophe.

This is not a doom and gloom book. I think the conceptual, policy-relevant advance in the book is to recognize that nuclear terrorism is in fact preventable because there’s a strategic choke point to the problem. It is a happy fact of physics that without fissile material – that is, highly enriched uranium or plutonium – you can’t make a fission explosion, and therefore you can’t have a nuclear terrorist act. Now the trick is to prevent any new production of highly enriched uranium or plutonium. They don’t occur in nature and they’re very very difficult to make. So we prevent production of new highly enriched uranium and plutonium, and we lock up all the weapons and materials that exist today to what I call a new gold standard, which would be the way we lock up gold at Fort Knox. It comes down to what I call the Three No’s: No loose nukes, no new nascent nukes, and no new nuclear weapons states.

But you mention in the first part of the book that there are about 200 places where terrorists can acquire nuclear weapons. How can we lock down a situation that already seems so out of control?

First, we would start with the United States and Russia. They have to agree to lock down all their weapons and all their material on the fastest feasible timetable to this new gold standard. Now since the U.S. and Russia have 95 percent of the stuff, there’s 95 percent of the problem. Then, in my scheme, the two of them go jointly to the heads of each of the other nuclear weapons states and invite them to join in a new alliance against nuclear terrorism. Then there are about 20 transitional countries like Belarus, Uzbekistan, and Ghana, where there’s highly enriched uranium at risky research reactors that should be removed. Since the reactors and the uranium came in most cases from Russia, but in a couple of cases from us, we would go to them and say, “This material came from us and we’re taking it back, and we’re going to convert the reactors so they’ll no longer use highly enriched uranium,” which is a pretty straightforward process. This should be done in no longer than one year.

How would you deal with countries that are now in the process of trying to build nuclear weapons?

We now have 184 countries that have voluntarily renounced nuclear weapons. This is a fantastic accomplishment that most people take for granted. Well, that whole system is right now under severe strain and at risk of collapsing, and the two countries that are at risk of collapsing it are Iran and North Korea. I have to have a strategy for freezing North Korea where they are and backing them down on a step-by-step basis, and that’s laid out in the book. In the case of Iran, I’ve got to stop them finishing their factories that will produce uranium and plutonium, because once they do that, they’re within months of producing nuclear bombs. In the book I lay out a strategy for a grand bargain for denuclearizing Iran. If we stop both these countries, which I believe is still possible, although it’s getting later every day, we’ll get a breather for a little while – not long, maybe two, three, four years – during which time we’ve got to do a lot of other things. One of these is delegitimizing nuclear weapons. Right now we’re telling the Iranians and the North Koreans, no, you can’t have any nuclear weapons, but we who already have 10,000 nuclear weapons, need a few more. It makes no sense, and in fact undermines our ability to draw the line with North Korea and Iran. So in that breather, what we should be about is the comprehensive test ban treaty that prevents testing. The only reason that’s not now law is that everybody else agreed to it except us. We need to ratify that so we’ll have no more nuclear tests.

Did our invasion of Iraq make any sense in terms of minimizing the possibility of nuclear terrorism?

In the vice presidential debate, Cheney said that we invaded Iraq because this was the most likely nexus between the terrorists and weapons of mass destruction. In my opinion, this is a case of mistaken identity. In the case of North Korea, they did have two nuclear weapons, or at least enough plutonium to make two nuclear weapons, which they acquired when Cheney was secretary of defense. The plutonium was locked in a set of fuel rods, and while we’ve been off in Iraq, the North Koreans have trucked it away and are producing bombs out of it. So while we were off in Iraq preventing Saddam from transferring nuclear weapons, which he didn’t have, to terrorists with whom he didn’t have ties, we gave a pass to North Korea and Iran. The logic doesn’t work. Bush in his axis of evil speech said there were three evil guys who were seeking weapons of mass destruction to hand over to terrorists – North Korea, Iran, and Iraq. And he shot the wrong guy!