Jennings practices the ‘theology of doing’

Minister’s journey from the mean streets and back

After Mark Jennings receives his M.Div. from Harvard Divinity School (HDS) today, he’ll end up right where he started: on the mean streets of one of the

nation’s toughest cities. But now, as the executive director of the Los Angeles Ten Point Coalition, he’ll be ministering to youth who are at risk for losing their souls – or their lives – to drugs, gang violence, lack of education and ambition. A decade ago, he was one of those kids.

As a poor black teenager in Washington, D.C., Jennings was on his way to becoming what he calls “one big statistic.” By the end of his teen years, he had two school expulsions and two suicide attempts behind him. It took a life-threatening holdup and a crushing mental illness before he realized his calling as a minister. God, it seemed, wanted to use him to show that the odds could be beaten.

God shares the credit for Jennings’ success – indeed, his survival – with several adult mentors who opened up his world beyond the harsh reality and sobering statistics of his neighborhood. In turn, Jennings has devoted his time at HDS – and his career – to work that is a homage to those who intervened for him. “The beginning goes with where I’m going now, because for me, it starts with mentoring I received,” he says.

‘One big statistic’

Jennings, a quiet yet strong presence in his black suit and white collar, had the sort of upbringing that’s become iconic for society’s urban ills. His parents split when he was an infant, his older sister now has five kids and struggles to stay off public assistance, his younger brother is in a Virginia prison serving a life sentence for murder. “I was probably headed down one of those roads,” he says.

Jennings’ first glimpse of the possibilities beyond his own world came at age 11, when George Washington University student Darius Anderson became his Big Brother. “I really credit him for helping me to expand my horizons, to be able to see that there are things in life that I can achieve,” says Jennings. Anderson, who is white, has remained a force in his life, even contributing to his tuition and living expenses at Harvard.

Several years later, as a high school sophomore unmotivated to study anything but black history, Jennings was arm-twisted by an English teacher into Children’s Express, a journalism program. Journalism brought Jennings accolades, bylines, and passion. “It gave me great confidence,” he says.

But it wasn’t enough. In his junior year, poor grades and general misbehavior got Jennings expelled from the magnet high school he was attending. “Life didn’t make sense in high school. Nothing seemed relevant,” he says. “Why do journalism? Why can’t I just work at McDonald’s? I didn’t see any hope in the community and I didn’t have any hope in me.”

Despite poor grades and subpar SAT scores, Jennings made it to college, only to be expelled in his first year. He slipped into dark days of waiting tables and battling depression. It took a holdup outside a nightclub to jolt him to action, both practical and spiritual.

“When the gun was to my head, I remember this indescribable feeling … there was almost a comfort that came over me and said, ‘You’re going to be OK.’ I felt that presence, I felt that was God,” he recalls. “Going through two suicide [attempts], a gun to my head, being kicked out of two schools, I felt like I needed to try to change myself, to do something.”

So Jennings literally talked his way into Howard University, where he thrived as a motivated student and budding journalistic talent. “I was doing everything I enjoyed and life seemed great and grand,” he says.

Then, in the summer of 1998, Jennings’ mental illness resurfaced, this time as a devastating bipolar disorder that hospitalized him. “It was just the worst time in my life,” he says, but it would lead to the best. “I began to realize that the purpose for my life was greater than just me and my achievements and accolades. I felt as though God wanted to use me to reach other people.”

Theology of doing

Harvard Divinity School, with deep roots in liberal New England religious traditions, was hardly an obvious educational choice for someone from the black Pentecostal church. In fact, the elders at Jennings’ church in Washington urged him not to attend, fearful that he would lose his religion – or have it taken from him. “They pray for me a lot,” says Jennings.

“Once I rededicated myself to the church, I knew I had the strength to come here,” he says. “While I did come holding onto my religion very tightly, at the same time, I was willing to just allow the school to really work on me, so that I could be the best preacher, the best theologian, the best communicator of religious ideas that I could be.”

Jennings has found the diversity of religious ideas at Harvard spiritually exciting. “Where else could you really go where you could sit down any given day and converse with Muslims, Unitarians, even atheists and agnostics, all in one place, and all discussing God?” he says. “I feel that here, people are still seeking.”

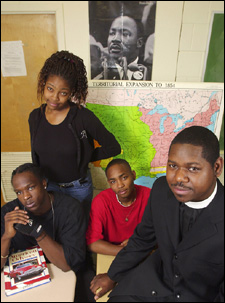

Harvard’s curriculum has also proved a great fit for Jennings’ interests. As part of HDS’s Program in Religion and Secondary Education, he was able to fulfill a lifelong desire to teach, doing a practicum at Boston’s Madison Park High School. But it was a course at the Kennedy School of Government on nonprofits that really lit Jennings’ fire. There, he learned about Boston’s Ten Point Coalition, an ecumenical coalition of Christian churches and lay leaders that mobilized to combat the rising gang violence and drug crime among black and Latino youth in the early 1990s.

Led by the Rev. Eugene Rivers and centered at his Azusa Christian Church, the Ten Point Coalition resonated with Jennings’ ongoing interest in interfaith cooperation around pressing issues. Before he arrived at Harvard, Jennings had started his own nonprofit, the Body of Christ Outreach Ministries. “In the black church, one of the things that really brings people together is the theology of doing,” he says. His own group, like the Ten Point Coalition, drew on this strength.

Ordained at Azusa last March, Jennings has found his church family and his spiritual calling in the work of reaching out to at-risk youth. After graduation, Jennings will move to Los Angeles with his family – his wife, Zerline, and young son, Jobe Darius – to take his ministry to troubled youth. He knows he’ll be staring his own history in the face.

“The ones that really catch my heart are the ones who were just like me,” he says of the youth he’s worked with. “The ones who are borderline, the ones who don’t come to school, the ones who I know could make it if they only were given some help. That’s all I want to do … [give] them that hope and understanding that they really have the power within them to transform society.”