Dangerous silences

Panel explores sexuality in black communities

Within the past several years, articles in the mainstream media have sounded an

alarm about a widening “black gender gap.” In African-American communities, women are outpacing men in professional and educational achievement, while incarceration and unemployment rates for black men far exceed those for black women. Some charge that this phenomenon is affecting marriage possibilities and family structures among blacks.

Leave it to a panel convened by the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute, however, to go beyond – far, far beyond – media-fueled fears of professional black women unable to find suitable husbands. Instead, Friday’s (April 23) “Gender and Sexuality in African American Communities” probed issues as far-ranging as AIDS/HIV infection rates, black men on the “down-low,” homophobia and the myth of African heterosexuality, intimacy and silence, and the latest video by Nelly.

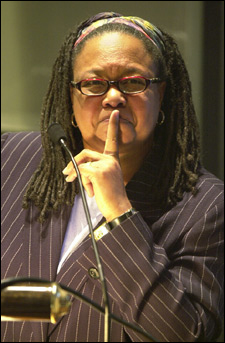

“This is a set of issues that some observers have suggested have risen to a crisis level in African-American communities,” said moderator Evelynn Hammonds, professor of the history of science and of African and African American studies at Harvard. “There has been a great deal of silence about sexuality and gender within these communities that has deep historical roots.”

“We are struggling as a people because of race, and race has taken the large energy that we have in our community,” said University of California, Los Angeles, psychiatrist Gail Wyatt. “Gender is getting pushed aside.” Joining Wyatt, author of “Stolen Women: Reclaiming Our Sexuality, Taking Back Our Lives,” on the panel were University of California, Santa Cruz, professor Tricia Rose and Spelman College professor Beverly Guy-Sheftall.

Perspectives from feminism and oral histories

Guy-Sheftall, professor of women’s studies and English and co-author of “Gender Talk: The Struggle for Women’s Equality in African American Communities,” presented a statistic she called “very disturbing,” not to mention surprising: that women of African descent who are most vulnerable to

HIV/AIDS are those who are married and have only one sexual partner.

While forcing a re-examination of current AIDS prevention efforts that focus on multiple sex partners and intravenous drug use, this fact speaks to an even more complicated issue in African-American communities, Guy-Sheftall said. Men who are on the “down-low,” that is who have male as well as female sexual partners but do not describe themselves as bisexual, are spreading HIV/AIDS to their wives, she said, and the community’s inability to talk about it has potentially devastating effects.

Through the lens of black feminism, Guy-Sheftall presented a laundry list of concerns, from the misogyny of hip-hop music – Nelly’s video of his hit “Tip Drill” was named as a top offender – to the black community’s difficulty in addressing silence around issues of gender and sexuality to violence against women and homosexuals.

The latter, she said, demands the same level of outrage from the black community as the gender gap, incarceration rates among black men, or racial profiling.

“We need black leaders to seriously consider issues of gender and sexuality as they try to imagine what it would be like to liberate black people in the 21st century,” she said.

Rose, a leading scholar of black culture, drew from the 20 oral histories in her newest book, “Longing to Tell: Black Women Talk About Intimacy and Sexuality” (Picador, 2004) to further shade the discussion. The women’s stories resist stereotypes, said Rose, yet present broad themes driven by what she called structural forces: the “color caste” system and its impact on women’s desirability, sexual double standards, and a sense of betrayal that’s related to the “down-low” phenomenon Guy-Sheftall discussed.

“The problem isn’t that he’s sleeping with brothers, the problem is that he’s not saying anything about it,” said Rose.

Drawing parallels between the intimate issues raised in the oral histories and the larger framework of social justice led Rose to create a model she called “intimate justice,” which seeks to relate the sexual double standard, betrayal, and color hierarchy to racism and larger problems of social justice.

“What would we do if we merged the language around social justice – the sense of outrage, the public sphere comfort we have around imaging a project of social justice as an ongoing one in the community – to the kind of intimate sphere concerns that have been addressed?” she asked. “I’m hoping that we can really think about the intimate sphere as a political place.”

Complicated by cultural values

With formidable academic credentials in the fields of psychiatry and sexual health and therapy, Wyatt presented her views in a plainspoken, motivational manner more Oprah than academic, eliciting more than a few calls of “that’s

right, sister” from the audience. The approach, echoed in her books that target a mainstream rather than an academic audience, is purposeful, she said; it helps her take her message directly to the black community that needs most to hear it.

Wyatt identified cultural issues and values that complicate issues of gender and sexuality in the African-American community. A strong community sense of interconnectedness; a historical legacy that permitted rape of black women – by black as well as white men; paranoia of health providers whose educational credentials trump their ability to understand and “be real”; and what she called “institutionalized sexism” that’s prevalent in black churches are all major forces in black sexuality today.

“Our churches are the most sexist pieces of our institutions, aren’t they?” she said. “We support them, but we don’t preach. I contend that not only do we need college sisters protesting, we need church sisters protesting.”

Like Rose and Guy-Sheftall, Wyatt pointed an accusing finger at the black community’s silence about sex. “You have to learn how to talk about sex,” she said, shocking and amusing the audience with stories of sexual misunderstandings between uninformed partners. “Some of what’s going on is about ignorance and silence and fear about talking about things.”

She called for increased community dialogue about gender and sexuality and for standing up against racist, sexist, and economic threats that face the black community.

In the spirited question-and-answer session that followed the panelists’ formal remarks, they focused increased attention on homosexuality, homophobia, and the “down-low” phenomenon; interracial relationships and color hierarchies; and role models in popular culture. Rose applauded female rappers for finding their voices and claiming a piece of a potentially lucrative pie, but the hypersexuality of too many of them, she said, made them little more than “strippers with rhymes.”

To one audience member who bemoaned the dearth of positive black female role models for the girls she teaches, Wyatt suggested that she point to admirable individual traits in women, helping the girls realize that heroines are nuanced and complicated people, too.

“You can tell them Beyonce is really talented, but her clothes are too small,” she advised.