Village convenes to help raise children

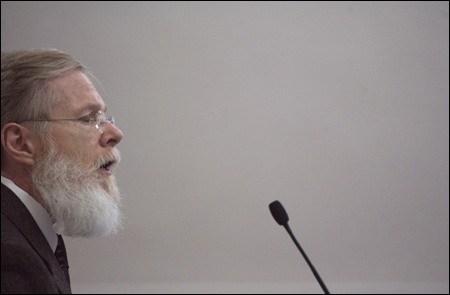

‘The need is greater than ever,’ says Mayor Thomas Menino

The proverbial village it takes to raise a child assembled itself at the Graduate School of Education (GSE) Friday (Feb. 6): Educators, social workers, policy-makers, health professionals, business leaders, parents, academics, and politicians, including the mayors of Boston and Providence, came from around the Northeast for a conference called “Building Strong Community Schools.”

While their professional roles are diverse, the conferees were united beneath the broad umbrella of engaging entire communities to support children’s learning.

“The best way to improve education in this country is to get schools and

For more information on community schools, visit the Web site of conference co-sponsor

the Coalition for Community Schools.

communities working more closely together,” said GSE Dean Ellen Condliffe Lagemann in her welcoming remarks. This close collaboration, she said, is at the heart of community schools, which link school and community resources as an integral part of their design.

“The need for community schools is greater than ever,” said Boston Mayor Thomas Menino. “Community schools strengthen schools, the family, and community so that together, we are able to improve children’s learning.”

Warning that he was “going where people don’t want me to go,” the mayor placed some of the blame for schools’ shortcomings on himself and his fellow lawmakers and leaders. “It’s great to stand up here and talk about education, but we now have to put some money behind it,” he said. “We’re not funding these programs the way we should.”

Not surprisingly, the conferees greeted Menino’s comments with an outburst of applause. Menino, as well as the other speakers and panelists in the daylong, sold-out conference, was preaching to the choir. As Providence Mayor David Cicilline joked, “This is so obvious. They have conferences about this?”

Yet as the No Child Left Behind Act holds public schools – never suffering from too much money or too few challenges – increasingly accountable for measurable success outcomes, the focus of community schools on the child’s whole world meets with resistance.

“Part of what needs to be addressed is [that] the present education reform framework is too narrow and too limited to really educate all of our children,” said Martin Blank, director of the Coalition for Community Schools, which helped sponsor the conference.

Findings from research and practice

Lloyd Kolbe drew on his experience as founding director of the Centers for Disease Control’s division of adolescent school health to illustrate the parallels between public health and community schools. The public health system relies on a complex web of community members and services, from health professionals to elected officials, public safety to religious organizations, schools to parks.

Community schools weave a similarly multilayered network of services together to support the whole child. Champions of the movement believe this approach is crucial for children to succeed. While high-stakes tests and the preparation for them may ensure academic competency, they’re incomplete without social services, health care, parental and family involvement, and after-school and recreational opportunities, say community school supporters. All of these resources exist in the community; community schools tap them and integrate them tightly into the education of the child.

Blank, the Coalition for Community Schools director, briefly presented findings from a report he co-authored called “Making the Difference: Research and Practice in Community Schools.” Fifteen of the 20 schools the researchers examined showed academic gains, but Blank says that community schools go beyond academics.

With a nod to the multiple intelligence work of Howard Gardner, Hobbs Professor of Cognition and Education at the GSE, Blank noted that community schools provide learning opportunities that develop a variety of competencies, academic and nonacademic. By engaging the resources of parents and community members, the report found, community schools reduce the burden on teachers and principals – crucial as our nation’s schools face an impending teacher shortage.

What’s more, said Blank, community schools build sought-after social capital in the communities they serve. “Schools need to return to being centers of our communities,” he said. “We have a case to make, and we shouldn’t be shy about it.”

No one can do it alone

At panels and roundtables throughout the day, the educators and community leaders took a 360-degree look at the promise and challenge of community schools. How do we build effective partnerships? How do we best engage parents and families? What role do school facilities play in creating community schools? How do we evaluate our success? Where does the money come from?

“All of us believe that our children … can achieve high standards,” said Patricia DiNatale, leader of Boston Public Schools’ Cluster 5, serving the Allston-Brighton and Mission Hill neighborhoods, and principal of the Horace Mann School for the Deaf. “Schools can’t do it alone, agencies can’t do it alone, and families can’t do it alone. There needs to be a structure in place that brings these folks together to wrap their services around children.”