Jerusalem during the reign of King Hezekiah

New exhibition at the Semitic Museum re-creates numerous aspects of ancient Israel

You’ve read The Book. Now see the exhibition.

The Semitic Museum has installed a new exhibition that brings the world of biblical Israel into vivid, three-dimensional reality. “The Houses of Ancient Israel: Domestic, Royal, Divine” immerses the viewer in Israelite daily life around the time of King Hezekiah (8th century B.C.), creating an experiential environment based on the latest archaeological, textual, and historical research.

The exhibition is an outgrowth of a recent book by Lawrence Stager, the Dorot Professor of the Archaeology of Israel, and Philip King, professor emeritus of biblical studies at Boston College. The book, “Life in Biblical Israel” (Westminster John Knox Press, 2001), brings together practically everything that is known about ancient Israel ranging from food, clothing, and family relationships to the esoteric concepts of religious life.

“It’s one thing to talk about these things but quite another to visualize what the artifacts looked like and how they worked,” said Stager. “The book was a great challenge to Phil King and me to re-create things from texts and archaeology, but it was a further challenge to put this information into three dimensions.”

In addition to Stager, the curators who took up this challenge were James Armstrong, Joseph Greene, and Helena Wilde Swiny, all of the Semitic Musuem.

The centerpiece of the exhibition is a full-scale Israelite house, open on one side, filled with authentic ancient artifacts that show how life was lived by common inhabitants of ancient Jerusalem. Agricultural tools, a cooking area, and a stall occupied by a single, scruffy ram fill the ground floor of the cube-shaped, mud-brick structure, which, thankfully, is not olfactorily authentic. The upper story, reached by a ladder, is devoted to eating and sleeping.

The house was created by Mystic Scenic Studios, a custom design and fabrication company in Dedham. Based on information derived from numerous archaeological excavations, it has a sense of reality that seems to become stronger the closer one examines it. The reality is enhanced by the absence of labels, which the curators decided would detract from the experience. All relevant information pertaining to the house is contained on panels on the other side of the room.

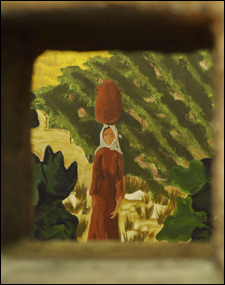

Another element that supports the feeling of authenticity is the lovely mural showing the cultivation of figs, grapes, and grain outside the city. The mural was painted by Diane Gilson.

But the humble details of everyday life constituted only one level of Israelite society. According to Stager, biblical Israel consisted of a series of households conceptually nested inside one another. At the lowest level was the family, presided over by the paterfamilias. Above him was the king, who was seen as the paterfamilias of the state or larger tribal group. Finally, God, or Yahweh, ruled over all, including the king, as the ultimate father figure.

In each of these relationships, the inferior is obligated to show loyalty to his superior, while the superior provides aid and succor to his subjects.

Stager sees ancient Israelite society as a series of multileveled relationships rather than a class system. It is an idea based on biblical evidence as well as analysis of inscriptions and archaeological sites. Linguistic evidence corroborates the concept. The same Hebrew word ebed can refer to a slave as well as to a high government official in his relation to the king.

“This is not a Weberian or Marxist theory that we are imposing on the society. We’re trying to see what best fits their own understanding of themselves,” Stager said.

While the ordinary household occupies the central place in the exhibition, the royal and divine realms are brought to vivid life as well. One corner of the exhibition space evokes a royal palace in ancient Israel.

We know from the Bible that Israelite kings employed Phoenician artisans, considered the finest craftsmen in the ancient Near East, to construct their palaces, and so a study of Phoenician archaeological sites provides additional hints of what these great structures looked like. The exhibition includes some palatial architectural details based on this evidence, plus an assortment of royal artifacts-some cosmetic containers that might have been used by the original painted lady, Queen Jezebel, and some limestone weights representing King Hezekiah’s standardization of weights and measures.

The Temple of Solomon is a structure that has been lost to history but re-imagined many times with wildly varying degrees of plausibility. The exhibition brings the temple to life through a magnificent multileveled painting by National Geographic artist Christopher Evans, based on the most up-to-date research.

The stone structure is shown surrounded by palm trees, olive trees, plane trees, and cedars of Lebanon – a carefully cultivated garden symbolizing paradise on earth. White-robed priests officiate at the great altar where animals are sacrificed, and tend the mekônôt, or wheeled stands containing sacred water.

Between the great bronze pillars, Jachin and Boaz, the doors of the Temple stand open, affording a view of the interior, forbidden to ordinary Israelites. At the back of the interior space, in which every surface is covered with gold leaf, stands the Holy of Holies, the symbolic throne of God between two gold cherubim. These are not the hovering toddlers of Renaissance paintings, but fierce, composite creatures resembling winged sphinxes.

The painting is replete with other fascinating details – symbolic motifs, ritual objects, authentic construction details – all of them based on exhaustive research and interpretation. As in the rest of the exhibition, the details draw the viewer in, evoking a world that is familiar in certain respects, yet intriguingly strange and alien.

“I think this is the best reconstruction of Solomon’s temple ever done because we have more clues now,” said Stager.