Australian butterflies ‘invade’ Harvard:

It’s a dazzling, iridescent, spotted, striped, and speckled sight

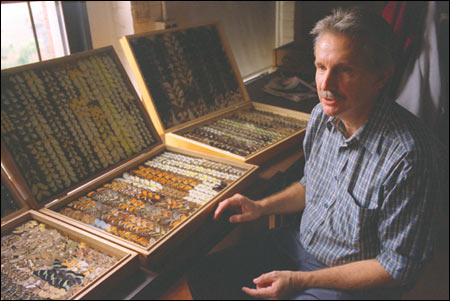

More than 15,000 butterflies from Australia have moved into Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology. They wear iridescent blue, green, and silver; boast black, red, and white spots; and flaunt color combinations beyond the imagination of hip fashion plates.

It’s the largest collection of Australian butterflies in the United States, representing 76 years of dedicated collecting by two friends. Some of the showy insects have gone extinct since these specimens were captured.

If you imagine geeky guys tripping though spring-gladdened glades with long-handled nets, forget it. One of the dedicated collectors, Rod Eastwood, labored for 30 years chasing butterflies up steep hills in eastern Australia, across the western deserts, and from Tasmania in the south, to the tropical heat of the Northern Territory. On the way, he was bitten by a red-bellied black snake, attacked by bulldog ants, chased by crocodiles, and stranded by swift-flowing rivers.

“The butterflies will be integrated with a smaller collection already here, and the combined holdings will represent the most comprehensive collection of Australian butterflies outside of Australia and the British Museum in London,” explains Eastwood, a genial, fit-looking fellow in his mid-50s. “The specimens I brought to Harvard include those collected by my good friend Ray Manskie, who worked at the task for 46 years.”

The butterflies will be used for public displays, education, and studies of everything from their genes to genitalia. Eastwood is working as a Fulbright Scholar in the laboratory of Naomi Pierce, Hessel Professor of Biology and Curator of Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths).

Life changes

For Eastwood, scholarly work on butterflies is a second career. He was a production engineer in plastics and rubber manufacturing for 27 years. Then he decided to learn about butterfly evolution and their genetic relationships. Eastwood earned his undergraduate degree at Griffith University in Brisbane. After unpacking butterflies and doing research at Harvard during the next 12 months, he will return to Australia to complete his Ph.D.

“It’s been a bit of a life change,” he says with a smile.

Interested in nature since his teen years, Eastwood liked to wander through the bush, collecting not only butterflies, but snakes, opossums, and other creatures. His wanderings involved climbing lots of steep rocky hills.

“If you want to collect butterflies, you’ve got to climb hills,” Eastwood notes. “Many species fly up steep cone-shaped hills to locate mates. Sometimes you’ll crest a hill and see hundreds of them flying around. There’s a definite hierarchy of flight zones; some prefer treetops, some mid-heights and others stay near the ground.

“You might see a particular stone on a bare patch with a butterfly resting on it. If you collect it, another one of the same species takes its place. Come back year after year, you always find that species on that stone.”

Experienced collectors don’t always go into net-waving frenzies on hilltops. They often shake the branches or peel the bark to find pupae, the cocoons where the insects make changes from a caterpillar to a winged adult. “You then can breed the insect at home, obtaining a perfect specimen rather than one whose wings may become tattered by a net catch,” Eastwood explains.

As larvae, a significant number of butterflies associate with ants. Some species disguise themselves as ant larvae to feast on the ants. Others develop a mutual relationship, a kind of juice scheme. Ants protect the budding butterflies in return for feeding on sweet secretions from butterfly larval glands.

“An unpleasant experience awaits those who collect Liphyra Brassolis, a butterfly that lives in the nests of green tree ants,” Eastwood warns. “It’s a ferocious ant that swarms and bites anything that comes into contact with its nest. They swarm over every inch of exposed skin, biting and squirting acid into the wounds.”

Half male-half female

As he carefully unpacks the iridescent, spotted, speckled, gaudy, and grand fliers from wooden boxes, Eastwood provides a running commentary on their habits and habitats. “This one,” he says, holding up a white specimen with red spots, “eats mistletoe.”

Pointing to a butterfly with one white and one black wing, Eastwood notes, “This one is half male, half female. It has no problem finding a mate. It’s also quite rare; you might see one in 200,000-300,000 specimens. I caught this one myself.”

The boxes hold skippers, darters, fritillaries, monarchs, and more. One has wings that look like leaves. Another has orange and black on its upper wings, black and silver on its lower wings. Some dazzle, some are plain, but Eastwood can tell you a story about each one. “These monarchs island-hopped across the entire Pacific Ocean,” he says with admiration.

Back in his office, Eastwood tells stories about the potential perils of pursuit. Snakes with one of the most potent venoms in the world, called tiapans, share the bush with butterflies. “I’ve been chased by them, but never bitten,” he says. “But I did get bitten by a poisonous red-bellied black snake.”

Collecting in the arid Northern Territory, Eastwood sometimes rested in patches of spring forest watered by subterranean streams. “But you must be careful,” he comments, “crocodiles frequently lie in the undergrowth during the dry season. They’re hard to spot, and you can sit on one without realizing it.”

Several times, he was surrounded and attacked by bulldog ants. “Huge ants with large jaws and a nasty sting,” he says. “In the far north of Queensland, I think I must have been stung by half the wasp species that live there. Beating them off or running away from a nest doesn’t deter them; they tend to attack even more. The options are to stand still and put up with a few additional stings until they lose interest, or leap into the nearest creek or billabong which is often crocodile infested.”

Eastwood tells funny stories, too. One time, he was collecting larvae with a Japanese entomologist on the outskirts of a town. The usual way to do that is to spread a sheet on the ground then beat or shake the tree to bring the larvae down. The Japanese collector didn’t have a sheet so he used a large umbrella held upside down. He also tied a large handkerchief around his head because it was a hot day.

As he worked at the end of a shady lane, a young couple who was lost drove up to ask Eastwood for directions. The man with the upside-down umbrella and handkerchief around his head came out from under the tree to see what was going on. The couple took one look at him and quickly drove off without waiting for directions.