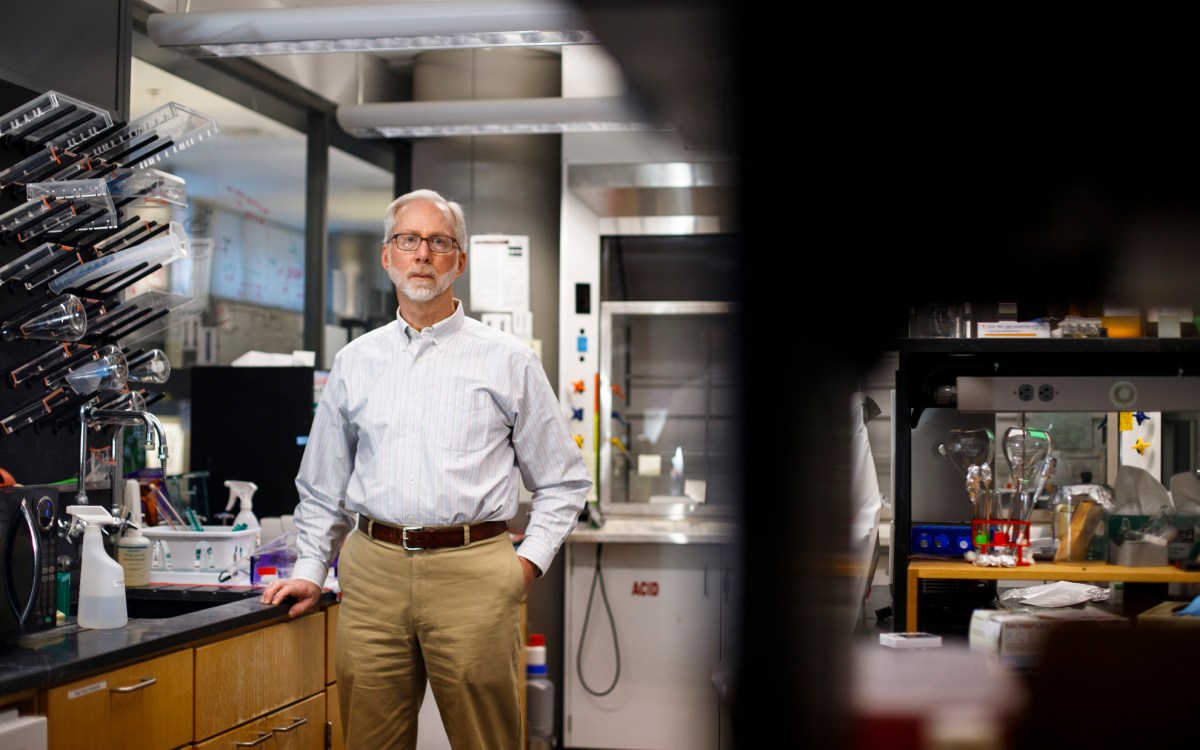

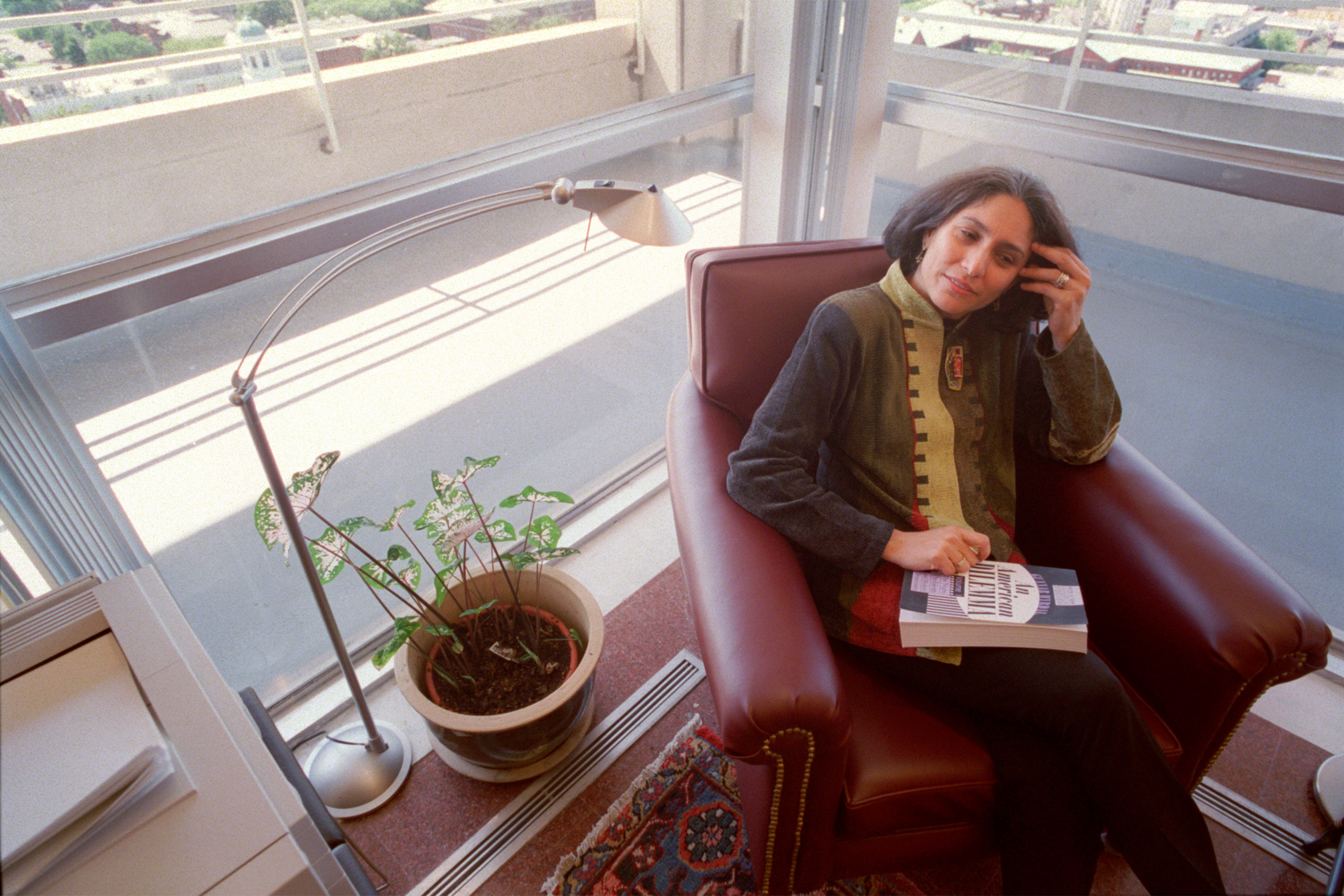

Mahzarin Banaji discovered that people, including herself, are more prejudiced than many of them think they are. The bias goes right to their brains.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Brain shows unconscious prejudices

Can’t wipe out years of evolution that made us fearful of the unfamiliar, but brains are flexible enough to be altered, notes researcherby experience

You may not think you are prejudiced against other races, gays, or overweight people, but your brain activity could tell a different story.

A brain area involved with fear flashes more actively when white college students are exposed to subliminal views of black versus white faces. The students didn’t actually “see” the faces, which were sandwiched between two patterns they viewed while undergoing brain scans. But they had a clear, deep-brain reaction to them.

The same type of bias shows up in website tests taken by hundreds of thousands of other people. They reveal unconscious prejudice against the elderly, gays, women, the obese, and a wide range of other groups.

Such brain and behavior tests might lead you to view the world as a grim place suffused with hidden hate and fear. But evidently things are not that bad. When white subjects undergoing brain scans see the black face long enough for it to register consciously, brain areas involved with controlled thinking become active. The differences in reactions to black and white faces then decrease.

“The imprint of culture is what we see in the subliminal exposure,” explains Mahzarin Banaji, Richard Clarke Cabot Professor of Social Ethics at Harvard University. “Seeing the face consciously allows thoughts and feelings to generate a more reasoned response to the face in view.” The research, done in collaboration with William Cunningham and Marcia Johnson at Yale University, suggests our conscious brain can lead us away from the prejudices of our unconscious mind.

“To the extent that we can influence what we learn and believe, we can influence less conscious states of mind,” Banaji notes. We can determine who we are and who we wish to be.

Shocked by bias

A liberal scholar of Indian background, Banaji was shocked when a computer test she uses to uncover prejudice in others revealed her own unconscious bias toward black Americans and elderly people. The test demands that a person quickly associate black faces, or those representing other groups, with “good” and “bad” labels. Test takers are given only a fraction of a second to respond, too little time for anything but a gut reaction.

“It was disconcerting and humbling to discover that my fingers didn’t move as fast when I paired black with good as they did when I paired white with good,” she admits. “I am neither black nor white, and I profess to hold egalitarian race beliefs. The results suggested that I should be skeptical about my own ability to be unbiased.

“At first, I didn’t believe such biases could be changed by anything short of a revolution that rearranges the social world as we know it,” she continues. “But my own students proved me wrong.”

One of her graduate students set up a good/bad, white versus black test that was supervised by a black researcher. White students in that situation showed less anti-black bias. “Just one black person exhibiting competence, being in charge, even for a short time, was able to change associations stamped into people’s minds over a lifetime,” Banaji concludes.

There’s no way to wipe out all the years of evolution during which humans and their ancestors learned to fear the unfamiliar, to be ready to run or fight at any threat. But brains are flexible enough to be altered by experience. “If this were not so, we would not have seen the reduction of bias in students who worked with a black researcher,” Banaji points out. We shouldn’t expect such changes to last long, but it does cause Banaji to feel optimistic about making behavioral changes that, though small and temporary, are real.

Harvard is a place where many portraits of distinguished white men stare from the walls of meeting and dining rooms. An effort to diversify the portraits to show more women and nonwhites is under way. Combined with other modifications in our surroundings, which include everything from television shows to background music, this sort of effort could subtly reduce bias, Banaji believes.

Against the elderly

Anyone can determine her or his own prejudices by taking the online tests. Those that measure race, ethnic, sex, and age bias are available at tolerance.org. You can view a test demonstration or, by giving some information about yourself, actually take a test. More than 60 different tests are also available at implicit.harvard.edu. Topics range from animals to politics.

Banaji and her collaborators put the tests online in September 1998. In the first month, after television and newspapers reported their availability, 40,000 tests were taken. Since then, information from 2.5 million of them has gone into research findings published by Banaji and colleagues.

The most troublesome result is a strong bias against elderly people. “It’s the largest bias we see,” Banaji says. “I was very surprised. People don’t openly discuss ageism much, like they do racism or sexism, yet its strong presence makes it much more insidious.”

You would expect such a prejudice to decrease with age, but it doesn’t. Responses show the bias remains large and robust from ages 8 to 68. “As people get older, they don’t necessarily think of themselves as “elderly,” Banaji comments. Fifty-year-olds think of 60- and 70-year-olds as elderly; 60-year-olds think of 70- and 80-year-olds that way. “Elderly” comes to mean “older than me.”

Information from the online tests doesn’t reveal why this is, but Banaji has some thoughts about it. “Age has come to be associated with negative qualities, such as decreases in stature, power, physical agility, and cognitive ability,” she says. “Of course that’s not true for everyone. I know a 78-year-old colleague who runs up stairs faster than his students.” Whether it’s myth or reality, however, generalization lumps everyone together.

Gays and women

More expected was prejudice against gays and lesbians. “We thought we would receive lots of angry mail when we added this test, because many Americans believe this is not a bias but an appropriate value to uphold,” Banaji recalls. “It turns out to be a prejudice that people are least concerned or ashamed about. People are not happy to see their prejudices against other races and older people revealed. But they don’t necessarily view an anti-gay bias with the same shame.”

There’s also relatively less shame in prejudice against the overweight. People show an implicit bias against the overweight and obese, but they are not too distressed about it.

Another unexpected finding reveals an unconscious feeling about women pursuing careers rather than staying at home. You’d think that would be strictly a male bias, but men and women show it equally. And to a startling degree. Eighty percent of test takers associate men with a “work” category and women with a “family” category.

Such prejudices are unconscious, of course, but they could influence things such as hiring and firing employees. “These tests are a research and educational tool to raise awareness,” Banaji points out. “They should not be used otherwise. We hope that the test results will leave each person to decide for him- or herself what they wish to do with this new knowledge that reveals they are sometimes less than they aspire to be.”