STAGE debuts with talk, pizzazz:

New group designed so Harvard students can form singing and dancing alliances with local public schoolers

It’s common knowledge that the United States is in the thick of a funding crisis for the arts. Less well understood is how the lack of funds affects arts education and still lesser known is how these consequences differ from urban to suburban school districts. These issues were tackled by a panel last Monday (May 5) at “An Evening for Art,” the debut event of Harvard STAGE, a student organization that aims to tap performance talents of university students to forge alliances with Boston Public School students.

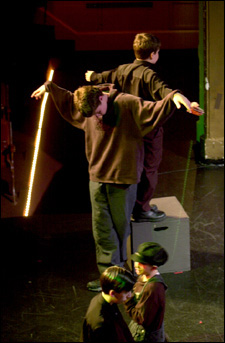

When the curtain rose on STAGE, or Student Theater Advancing Growth and Empowerment, at the Agassiz Theater, Boston Arts Academy students showed off stirring modern dance choreography to gospel spirituals, teens from Jonas Clarke Middle School in Lexington performed a quick-paced sequence by an abusurdist dramatist, and undergraduates were in razzle-dazzle form with jazzy song-and-dance numbers from “Chicago.”

“When Rebecca asked me to participate, I said, ‘of course’ because that’s what my job has been about for the past nine years,” said Alyson Brown, drama teacher at Jonas Clarke. “[Theater] supports history, it supports English. It helps [students’] presentation skills and confidence, which branches out into so many aspects of their lives.”

Before the students testified to the power of performance, the critical nature of STAGE’s mission was revealed through the insights of a panel of experts on the politics and theories of arts education. Moderated by Robert Orchard, executive director of the American Repertory Theatre, the impressive assembly was brought together because of a shared set of core values. Each expressing a distinct personal and professional perspective, the panelists addressed the notion that children exposed to the arts excel in other areas of their education and personal development.

“The arts are not a means for raising grades, but for developing a workforce our economy needs for the twenty-first century, people who can work collaboratively. … I’m mystified how many people don’t understand how critical arts are for development,” said David Marshall, program manager for the Education Department at the Massachusetts Cultural Council (MCC), the state agency whose budget to fund arts organizations was slashed by 62 percent last fall, a condition that has many anxious.

But according to Esther Kaplan, cultural affairs commissioner for Boston, there is less reason to be concerned about the repercussions of the MCC’s fiscal constraints than with the general cuts to public education. “Art is a public policy issue. Money needs to be spent on arts the same way it’s spent on science in schools,” she said.

STAGE came into being because of the pluck and planning of Rebecca Rubins ’05, whose interests in the performance and production aspects of theater have carried over from when she was in high school in Minneapolis. At Harvard, she has acted, stage managed, and done publicity for plays and musicals.

“Harvard students do a lot of great shows, but it often feels insular. The same people come to the shows, they’re in the same spaces, and the money all goes back into the organization. There’s so much talent here, it would be great to channel that into the [broader] theater scene,” Rubins said.

To launch STAGE into the spotlight, Rubins and Robbie Pennoyer ’05 corralled a student board and an advisory board, which includes Judith Kidd, director of Phillips Brooks House (PBH), and David Illingworth, dean of undergraduate activities. The group, which is a member of the PBH Public Service Network, plans to hold auditions in the fall for a theater troupe that will head up an after-school program in a Boston public school without an arts component. Members will lead children through the process of production, from self-expression exercises to playwriting to staging a work. At the end of the year, students will perform their play on a double bill with a STAGE production at a Boston venue, with all proceeds going to a city arts organization that has applied for the funds.

While the panel was unanimous on how arts should be a right, not a privilege, for all public school children, a cautious declaration of the importance of advocating was voiced by Howard Gardner, professor of cognition and education at the Graduate School of Education (GSE) who has pioneered the theory of multiple intelligences. “Arts involve the mind in multifarious ways, but you need to be aware of specious arguments because they’ll haunt you. You must be aware of the better arguments if you want to be an advocate,” he said, noting that too many make the case that arts education boosts standardized test scores without concrete evidence.

“From my perspective, it’s not a crisis in funding for the arts, but how the country feels about urban poor children of color. It’s a crisis that speaks to our disdain – our dislike – of otherness. Urban children are the ones constantly clawing at the resources,” said Linda Nathan, headmaster of Boston Arts Academy, a charter school and the city’s first public performing arts high school.

“When young people are given opportunity, they shine in ways they never found before. Art reinforces a certain work ethic that succeeds where other academic fields may fail,” said Jarrett Barrios, the state senator who represents Middlesex, Suffolk, and Essex counties.

With so many city agencies strapped for cash and staff, STAGE emerges primed to supply public school students with college students’ talent and enthusiasm – at no cost to the system – and offers a model for other universities.