Recovering looted and lost Iraqi treasures

A barrage of editorials and letters to the editor have appeared in the press in recent weeks charging that the U.S. military ignored the advice of experts on Middle Eastern art and archaeology about what needed to be done to protect Iraq’s cultural heritage after the fall of Saddam Hussein’s government.

Now many of those same experts are putting their anger and disappointment aside and cooperating in an international effort to recover as many of the lost treasures as possible.

A number of Harvard faculty members and librarians are contributing their time and knowledge to these salvage operations.

“It’s more constructive to do whatever we can do now to recoup these losses,” said Irene Winter, the William Dorr Boardman Professor of Fine Arts. “The more you get stuck in finger-pointing, the more people are going to get defensive and so resist what can be done at this point.”

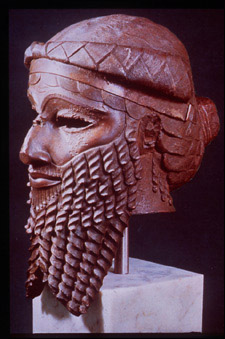

Winter, an authority on the art and architecture of ancient Mesopotamia, has been working with archaeological organizations, museum officials, UNESCO, Interpol, the FBI, and various government agencies in an effort to compile an accurate inventory of the objects that have been stolen or destroyed and to institute policies that will facilitate the return of looted artifacts and the protection of vulnerable archaeological sites.

“It’s been exhausting, but I’ve learned a great deal about finding the right vocabulary and the right pressure points to use in Washington,” she said.

Since April 10, when looters first began ransacking the Baghdad Museum, estimates of the extent of the damage have varied wildly. So far, because of the uncertainty of the situation and the danger involved, the U.S. government has not allowed teams of qualified experts into Iraq to conduct a thorough inventory of the country’s museums, libraries, and archaeological sites. But according to Winter, such an assessment is a necessary first step in any recovery process.

“Until an inventory is done, we will not know the extent of the damage or losses. It would be counterproductive to minimize those numbers or to inflate them.”

In the meantime, however, there have been news reports, eyewitness accounts, and estimates of various sorts. Based on this information, Winter and others have arrived at guesstimates of the damage.

Of the 170,000 objects the Baghdad Museum possessed, Winter believes that several thousand are still unaccounted for. About 400-odd objects have already been returned under an amnesty program, mostly by people who said they took the pieces to protect them.

But these numbers fail to do justice to the extent of the devastation that has been wreaked on an institution that has been described as one of the three or four most important archaeological museums in the world. Recent photos taken by John Curtis, Keeper of the Department of the Ancient Near East at the British Museum, tell a disheartening story.

“The place is a disaster area,” Winter said. “The galleries and storerooms have been trashed. There are broken potsherds and fragments of statuary everywhere.”

The damages to the Baghdad Museum may pale in comparison to those sustained by the Iraqi National Library, which was devastated by fire.

Lesley Wilkins, the bibliographer for law of the Islamic world at Harvard Law School, agrees with Winter that until an accurate survey of Iraq’s cultural losses is conducted, the extent of the damage will remain undetermined.

Wilkins, who is vice president of the Middle Eastern Librarians Association, will be attending a meeting on May 26 in Beirut of the Middle Eastern Librarians Committee International where the main topic of business will be what to do about the destruction of Iraqi libraries.

“What I hope to hear in Beirut is that someone is planning such a survey, perhaps under the auspices of UNESCO,” Wilkins said.

In addition to obtaining an accurate inventory, another essential step is getting the museums and libraries repaired and operating again.

“No one is getting paid, so there’s no incentive to return to work, and with continued looting and civil unrest, many employees, particularly women, are afraid to return,” said Andras Riedlmayer, the bibliographer in Islamic art and architecture in the Fine Arts Library. “We must make it a priority to pay and ensure the safety of trained staff, or they won’t show up,”

According to Winter, while the National Endowment for the Humanities and the State Department may help set up study and conservation groups in this country, USAID and other federal agencies could help pay for repair, needed technology, and staffing of museums and libraries in Iraq.

Riedlmayer and his colleague Jeff Spurr, the Islamic art cataloger in the Fine Arts Library’s Aga Khan Program, have been active in an international effort to rebuild Bosnia’s libraries and museums, many of which were destroyed during fighting in the early 1990s. Now they plan to include Iraq’s institutions in their rescue efforts.

According to Spurr and Riedlmayer, what librarians and scholars can do now is to gather and coordinate information on manuscripts, books, and art objects known to be in Iraqi collections and to disseminate this information to dealers and auction houses where such material is likely to turn up.

Some of this work is already under way. The University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute has set up a Web site showing objects known to have been stolen, and the International Council of Museums has compiled a “red list” of objects most likely to turn up on the illegal market.

“The United States has a relatively good track record compared with other collecting countries of addressing the illicit market in art, but still, more needs to be done,” said Winter. “We’ve been working to get both national and international legislation in place to ban the sale of these objects in Europe, the United States, and Japan. That way, we can inhibit the market at the demand end.”