Health care: Success or demographic nightmare?:

Aging global population presents challenges

An aging global population presents a demographic nightmare that will have fewer working young people supporting larger numbers of retirees, raising the specter of fiscal deficits, economic stagnation, and a decline in the global position of today’s Western powers.

Or not.

Instead it might be the culmination of decades of improvement in health care, creating a future where an aging but healthier population blends its needs and capabilities with younger generations and where population declines ease the pressure on environmental resources.

It depends on who’s doing the talking.

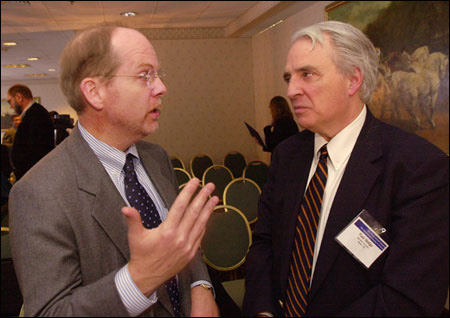

Last week, Paul Hewitt of the Global Aging Institute at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C., and Victor Marshall, director of the University of North Carolina Institute on Aging, presented their contrasting views of the future. Hewitt, who adopted a decidedly catastrophic tone, contrasted to Marshall’s less strident view, which was pointedly critical of Hewitt’s presentation.

Neither debated the basic figures, however, which were presented by Victoria Velkoff, chief of the Aging Studies Branch of the U.S. Census Bureau.

Velkoff, Hewitt, and Marshall were part of the Global Aging Symposium, co-sponsored by the John F. Kennedy School of Government’s Generations Policy Project. The project, founded by Paul Hodge, a fellow at the Center for Business and Government, aims to spur the debate on policy changes needed to meet the challenge of an aging population. The symposium was part of the Gerontological Society of America’s annual meeting at the Boston Marriott Copley Place.

Velkoff said that aging of the global population – driven by rising life expectancy and falling birth rates – will occur in developing countries as well as in developed countries, though the elderly will make up a larger portion of the developed countries’ population.

She said countries such as Italy, Germany, and Japan will have nearly 30 percent of their population age 65 or older by 2030, and sub-Saharan African countries like Zimbabwe and Botswana, which are experiencing large numbers of deaths from AIDS, will have many youth and many elderly, but few in between.

“Population aging will become the most important demographic factor affecting families around the world,” Velkoff said.

Another wrinkle to the future mosaic is population decline, she said. Driven by declining birth rates, 30 countries are expected to have declining populations by 2030, with 11 countries having declines of more than 1 million people. One factor that may be surprising, she said, is that six of those 30 countries are developing nations.

The result of these figures is potentially serious, Hewitt said. With economic activity concentrated in a person’s younger and middle years, having a large elderly population will potentially slow economic growth and require a surge in government services at the same time.

“The world stands on the threshold of a great demographic revolution. And when it’s done, nothing will be the same,” Hewitt said.

Hewitt said the fiscal demands of providing services for the large numbers of elderly residents at a time when working-age residents are becoming fewer and fewer has potentially severe consequences. The economic impacts can extend beyond government budgets, as the elderly stop saving for retirement and begin withdrawing money from financial markets. Saving and investing rates will fall, he said, as will demand for consumer goods and services.

“Global aging is pushing developed countries to fiscal meltdown,” Hewitt said.

The consequences can be so severe that it shifts the balance of economic and global power toward nations with younger, more vital populations.

“If demography is destiny, global leadership may pass from the first to the third world,” Hewitt said.

Though Marshall decried Hewitt’s doomsday language, both agreed that the world is indeed aging and solutions need to be found for the potential financial squeeze. They said governments could consider increasing the retirement age, though Marshall said simply mandating that people work longer isn’t the answer. He disagreed that elderly workers are less productive than younger workers and said working conditions can be changed to encourage the elderly to work longer. He gave as an example brighter lighting to aid fading eyesight and seating that keeps workers from repeatedly standing and sitting.

“If opportunity, rather than compulsion, is the issue – job sharing, shorter workweeks, longer vacations – some will prefer to enter retirement through a gradual transition,” Marshall said.

Marshall said the answer might be found in boosting workforce participation. Some nations facing aging populations don’t have women participating in the workforce as much as men while other nations have high unemployment rates.

Whatever the solution, Marshall said, nations are not prisoners to demographic trends. Societal structures, he said, are due to government and societal priorities, which can be changed.

“That people are living longer and fertility rates are falling is usually cause for joy,” Marshall said.

Hodge, one of two who led discussion on the debate, said the answer might lie in the present, not the future. By focusing attention on the issue today and encouraging collaboration, Hodge said, policy-makers will have the chance to make whatever adjustments are needed.