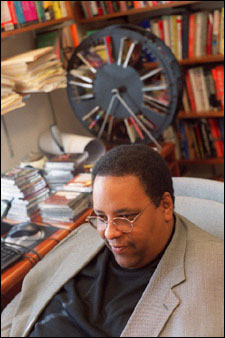

Michael Dawson explores black political thought, now and then:

Professor of Government seeks to understand political visions and behavior of African Americans

To explore the political visions and behavior of African Americans, Professor of Government Michael Dawson looks to history and asks questions about the present. He goes to church and the voting booth, workplaces and the unemployment line.

“Looking at black civil society, it’s very difficult analytically to separate cleanly political from social, economic from religious,” says Dawson, who came to Harvard in July from the University of Chicago, where he chaired the political science department. “When we look at black civil society we have to take a fairly broad analytical brush.”

Dawson has applied his brush to the study of race and politics in the United States. His 1994 award-winning book “Behind the Mule: Race, Class and African American Politics” (Princeton University Press) probed African-American political beliefs and voting behavior. He was principal investigator of the 1993-94 National Black Politics Study, which surveyed 1,200 randomly chosen African Americans to explore – for the first time – the relationship between the political ideologies and political beliefs of African Americans.

Black visions, throughout time

Dawson’s most recent book, “Black Visions: The Roots of Contemporary African American Mass Political Ideologies” (University of Chicago Press, 2001), brings a historical perspective to black political ideologies.

“The work tries to assess, using public opinion materials as well as other types of archival materials, to what degree do some of the historically important political ideologies within the black community still have influence on contemporary black public opinion,” he says.

The answer, he says, is uneven, fluctuating from era to era.

“We don’t want to look at public opinion as being static, because these traditions change over time,” he says. During his college days in the 1970s, for instance, many ideologies competed to capture the black political agenda. Joining black liberalism were black Marxism, the very powerful force of black nationalism, the early rumblings of black feminism, and even a small but growing black conservative movement.

“You had extremely active, on-the-ground organizations of almost all ideological stripes competing 30 years ago,” he says.

Today, he says, the ideological picture is more monochromatic and less grassroots. Black liberalism remains dominant but less attached to community organizing.

“There’s an organizational vacuum now that did not exist 30 years ago,” says Dawson.

Not surprisingly, Dawson’s own history informs his work. A Chicago native, he comes from a family that has been involved in that city’s politics for 40 years. The other side of his family, from Cleveland, was active in the civil rights movement.

“I had a front-row seat as a youth to both the informal and formal relationship between race and politics in the middle part of the 20th century,” he says.

Coming into young adulthood and going to college in the late 1960s, when campus activism focused not just on the Vietnam War but on issues of black studies, minority recruitment, and diversity as well, cemented race as a central theme of his academic life.

The changing roles of black institutions

Dawson’s current work builds on his previous studies while taking him into new directions. He’s expanding his political perspective to embrace social and economic institutions’ roles in race and civil society.

Historically, he says, black civil society has rolled economic, social, political, and religious functions together, largely because of the prominence of the black church in African-American society since the 19th century.

Looking nationally and drilling down to the local level in select cities, Dawson is exploring the changing roles of historically important black institutions and the shifting boundaries between the public and the private in black communities.

A complex picture is emerging, he says, pointing to the eroding of those boundaries in Chicago. There, as social institutions weaken, government organizations are taking over welfare functions.

“If you want to look for a job you go to the police station because that’s where the job information is,” he says.

This new role of police may not extend beyond the Windy City, he says, but the weakening of historically important black institutions is not unique to Chicago.

“One of the questions we’re asking is what institutions are taking their places,” he says. As black churches and civil rights organizations see their membership aging and shrinking, other community-based groups, state or local government forces like the police, or new Christian denominations may be filling the void.

“There’s a variety of candidates, including none of the above, that may be taking the place of institutions that traditionally played such a strong role in the black communities,” he says.

New tools for traditional techniques

With Lawrence Bobo, the Norman Tishman and Charles M. Diker Professor of Sociology and of Afro-American Studies at Harvard, Dawson is also turning his attention to the more tangible manifestation of black political ideology: elections. The two are engaged in a project that explores the racial divide at the time of the 2000 presidential elections in the United States, looking at racial difference in support for policy issues, presidential candidates and other political leaders, and reparations for slavery.

Dawson and Bobo are also at work rebuilding one of the social sciences’ most elemental tools: data collection.

Dawson credits his “traditional” training – at the University of California, Berkeley, as an undergraduate, his doctoral studies at Harvard, and an assistant professorship at the University of Michigan – with grounding his data collection and analysis methodologies. Yet he and Bobo are pushing the boundaries of the social science survey by developing new online data collection techniques.

“It’s becoming increasingly difficult to carry out a high-quality telephone survey,” he says, with voice mail and screening technologies thwarting this traditional data-collection tool. “We absolutely have to have new methodologies to be able to do scientific surveys of public opinion.”

They’re exploring the use of online data collection, selecting households randomly, as with a telephone survey, then outfitting them with a Web TV through which they conduct the survey and deliver supporting materials. While analyzing the data, they will also be scrutinizing the effectiveness of the survey method.

‘Where people talk about race and politics all the time’

Dawson and Bobo have collaborated several times throughout their careers, and Bobo is predictably pleased to have Dawson on campus.

“Michael Dawson is the leading analyst of contemporary African-American political thought and behavior. He … brings together the richness of the black experience and influence in and on American politics, with rigorous empirical analysis, and broad theoretical ambit,” says Bobo. “We are exceedingly lucky to have persuaded Michael Dawson to come to Harvard. He is a scholar of the first order of intellect and a teacher of inspiring gravitas and vision.”

For Dawson, the intellectual opportunities afforded by being in the same physical community as Bobo and some of his other respected colleagues – in addition to the excellent career prospects for his wife, an epidemiologist, in the Boston area – drew him back to Harvard from Chicago.

Although he has high praise for the University of Chicago’s political science department and was founding director of the University’s Center for the Study of Race, Politics and Culture, “we had nothing like Harvard’s Afro-American Studies Department or the Du Bois Institute,” he says.

“Being in an environment where you can talk with Bobo or [Henry Louis] Gates or [William Julius] Wilson or Evelyn Higginbotham or Jennifer Hochschild – having an environment where people are talking about race and politics all the time – is very exciting and certainly helps create an atmosphere where it is much easier to do one’s work,” he says.