Chilling story of a reluctant soldier:

Ugandan woman was forced to serve in army at 8 years old

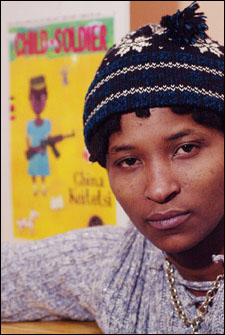

China Keitetsi’s autobiography is currently number two on Germany’s best-seller list. Its title is “They Took Away My Mother and Gave Me a Gun,” and that is literally what happened to her.

At the age of 8, Keitetsi wandered away from her village in rural Uganda and became lost in the bush. She was found by two men who were soldiers in the rebel army of General Yoweri Museveni, then fighting against the government forces of President Milton Obote. The men recruited her as one of Museveni’s child soldiers.

Since that time, Keitetsi’s life has been a harrowing odyssey, which, miraculously, she has managed to survive. Now 26, she lives in Denmark and has devoted her life to ending the use of children as soldiers, a practice that is alarmingly common worldwide. According to U.N. estimates, there are at least 300,000 combatants younger than 18 fighting in conflicts around the world. Keitetsi spoke last Thursday evening (Nov. 7) at Emerson Hall in an event co-sponsored by the Harvard African Students Association, the Center for International Development, and the Committee on African Studies.

Keitetsi was given the name China by a superior officer who thought her eyes looked Asian. Small, dressed in jeans and a sweater, she does not seem like a hardened soldier, but by the age of 17 she was already a veteran of many deadly battles. Today, when she remembers the people she has shot, she tells herself it was the gun that killed them, not her.

“You will never know how I feel inside,” she told her mostly undergraduate audience. “It’s like I have lived 100 years, because I have seen so much. It’s hard to talk about this, and if I cry, don’t feel sorry for me, because I am free. I am no longer told who to hate and who to kill.”

Conditions were even harder for girl soldiers than for their male counterparts, Keitetsi said. In addition to the general brutality of army life, girls were subject to systematic sexual abuse. She described the shame of being told by an officer to report to his barracks – knowing what was in store for her and knowing there was no one to whom she could turn for help.

When she did reject the sexual advances of an officer, he accused her of selling guns to the enemy, and she knew that she would have to leave the country or be killed. She and a friend managed to escape and ended up in South Africa.

She survived for four years on the streets, then was recaptured by representatives of the Museveni government. They were about to bring her back to Uganda when she escaped and went to an Afrikaner immigration officer for help. He put her in touch with U.N. authorities, who found a home for her in Denmark.

While living in Copenhagen, Keitetsi began seeing a therapist who tried to get her to tell her story as a way of dealing with the crippling residue of trauma that she still carried with her. Unable to describe what she had gone through to another human being, she found that she could describe her experiences into a tape recorder. It was these narratives that became the basis of her book.

Keitetsi has spoken to groups throughout Europe about the plight of her fellow child soldiers. Protected by the Danish police, she feels safe, but, for her, going back to Uganda would be out of the question.

“If I go back, it’s like, OK, the lion is hungry – ‘Can I hide in your mouth?’ Museveni and his generals are very angry with me. It shows our president doesn’t care about freedom. He still uses children. In northern Uganda, kids are being taken every day to fight in the Congo war.”

Keitetsi was scheduled to tell her story at the United Nations in New York the following morning. From there, she will go on to other speaking engagements in the Northeast. While she believes that UNICEF and other organizations are working to end the use of children as soldiers, she feels that more is needed.

“We shouldn’t just trust to organizations. If everyone would look in their hearts, they would find an answer. The world is so big – we can do it!”

The solution to the problem, she said, lies in holding leaders like Museveni responsible for their actions. If that were done, it would discourage others from recruiting children.

“They have committed a crime against us, but we have not committed any crime. When all of the kids are safe, that’s when I will smile.”

But Keitetsi did have another reason to smile, and she shared the news of that good fortune with her audience. Two months ago, she reconnected with an old friend, a fellow child soldier from Uganda whom she had assumed was dead. Now in his 20s, he lives in Miami, where he is pursuing a boxing career. After her talk, Keitetsi planned to drive to New York, where the two would meet.

“Believe me, if this wasn’t Harvard, I would have canceled. We are going to talk all night, probably not get any sleep, even though I have to be at the U.N. at 9. I don’t know how I can explain this to you. We were best friends. I am so happy.”