Ah, Paris! The world capital of nostalgia:

New book looks at the ‘city of light’ as a maker of myths

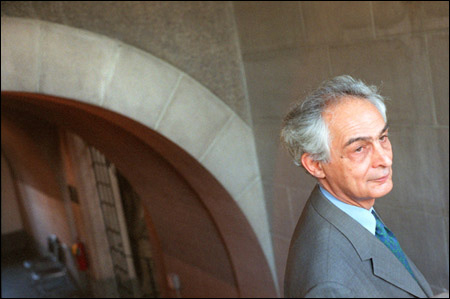

When Patrice Higonnet was invited to teach at the College de France, a venerable Parisian institution whose free lectures are attended by everyone from street people to the haut monde, he decided to do something daring – instruct Parisians about their own city.

“It was a death-defying act,” he says, “to teach the history of Paris in Paris.”

Higonnet, the Robert Walton Goelet Professor of French History, knew that a straightforward, sequential history of the city would not have interested his diverse but sophisticated audience. Such an approach would have been old hat. Instead, Higonnet decided to lecture on the myth of Paris.

Higonnet’s thesis is that between the mid-18th century to the mid-20th, Paris gave birth to a series of myths – fabulous and exalted ideas about itself that were embraced by people all over the world.

These myths changed almost decade by decade: Paris as capital of the modern self gave way to Paris, capital of revolution. Later, as the misery of the lower classes came into public consciousness, Paris emerged as the capital of crime. In rapid succession, it also became the capital of science and the capital of alienation. Finally, there was the myth of Paris as capital of pleasure, the “Gay Paree” of the fin-de-siècle period.

So successful were Higonnet’s lectures that he decided to turn them into a book. It was a formidable undertaking. He estimates that he read about 500 volumes on his subject, a mere sampling of the 10,000 or so that have been written about Paris since 1323 when the first book about the French capital appeared.

“This book wore me out. I’ve never worked so hard, even as an assistant professor at Harvard.”

Besides working in the library, he conducted a considerable amount of research on the broad avenues and narrow alleyways of the city itself. Often in the company of his daughter, he would travel to the end of one of the Metro lines and then walk back, exploring out-of-the-way neighborhoods rarely discussed in the tourist guides.

At nearly 500 pages, with 50 pages of illustrations, the book, “Paris, Capital of the World” (Harvard University Press, 2002), does ample justice to Higonnet’s extensive research. Though filled with obscure facts and quotations from a wide selection of writers including Diderot, Rousseau, Voltaire, Balzac, Baudelaire, Hugo, Zola, Henry James, Walter Benjamin, André Breton, and James Baldwin, the book is highly readable and entertaining, the translation by Arthur Goldhammer preserving much of the wit and playfulness of the French text.

“I wrote it to please,” Higonnet says.

Born in France, Higonnet moved here in the late 1940s when his father, the co-inventor of the photo-typesetting process, was invited to work in the United States. Higonnet attended Harvard, earning a bachelor’s degree in 1958 and a doctorate in 1964. He has been a member of the History Department since 1964.

Examining how the image and reputation of Paris evolved, Higonnet constructs “a history not of factual events but of the way the city has been perceived, conceived, and dreamed.”

He makes a distinction between myths and what he calls phantasmagoria. A true myth, he believes, is inclusive. For example, in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, when Paris was seen as the capital of revolution, radicals around the world looked toward the city as an inspiring example of freedom from aristocratic control.

“Revolution was seen as a path to salvation, and Paris showed you how to do it,” Higonnet says. “Radicalism didn’t die, but it ceased to have this demonstrative quality.”

Phantasmagoria, which has more in common with modern advertising, is a kind of illusion or self-delusion. For Higonnet, 1900 was the moment when Paris began to lose its true mythic character and instead began to self-consciously market its own image.

Today, Paris is still the capital of world nostalgia, its one remaining myth. It is also a kind of touchstone of style and sophistication.

“If you are a cultivated person, you’ve been to Paris,” Higonnet says.

While Paris can no longer claim mythic status, it is still a beautiful and vibrant urban center, Higonnet believes, and may still contain important clues to what it means – in its broadest sense – to be a European.

“A European,” he writes in the book’s last chapter, “is anyone for whom Paris might now or in the future hold a key to some form of self-understanding.”