Oldest Mayan mural found by Peabody researcher

Jungle ordeal leads to surprise treasure

William Saturno was hot, frustrated, low on food, low on water, and low on patience when he sought shade in a trench dug by looters at the San Bartolo archaeological site deep inside the Guatemalan jungle.

The arduous two-day trip there to document carved Mayan hieroglyphics had been in vain. The palace complex held 80-foot-tall pyramids, ball courts, and other structures, but no hieroglyphics. The exhausting trip back through the jungle awaited.

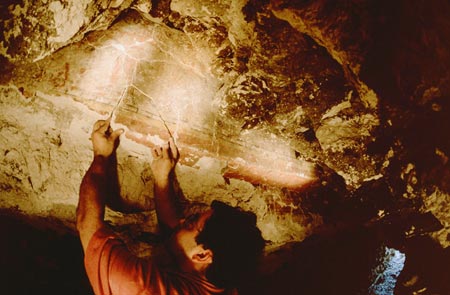

Saturno, a researcher for the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology and lecturer at the University of New Hampshire, explored the trench as his guides searched for water. A few moments later, his flashlight beam revealed what may be one of the greatest finds in Mayan archaeology, a 1,900-year-old depiction of a religious ceremony involving the maize god.

“I shined my light on the wall and I was suddenly less irritated.” Saturno said. “As soon as I saw the mural, I thought ‘This is extremely rare.’”

Though rubble filling the building still hides perhaps 90 percent of the painting, enough is exposed to see it is quite large, it’s in excellent shape, and it probably dates to 100 A.D. That would mean it was painted during a period of rapid change, during the transition from the Preclassic to the Classic Period, when Mayan civilization reached its peak. That also means it is 700 years older than the only other Mayan wall painting known, a large depiction of Mayan battle scenes discovered in 1946 at Bonampak in Mexico.

“If what we see there is any indication, this’ll be one of the great finds in Mayan archaeology,” said David Stuart, Bartlett Curator of Mayan Hieroglyphic Inscriptions at the Peabody Museum.

Maya mythology

Saturno, who received a doctorate from Harvard in 2000, was in Guatemala on the Peabody’s long-running project to catalog Mayan hieroglyphics, the Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions, directed by Ian Graham. Stuart is assistant director of the project.

When he returned to Cambridge, Saturno showed Graham and Stuart photographs of the find. When they saw the photos, Stuart and Graham realized how important the find potentially was. They scrambled to get emergency research funding, landing a grant from National Geographic, which is publishing an account of the mural’s discovery in the April issue of its magazine.

Saturno made his discovery in March 2001 but it was kept secret so researchers could further evaluate the site and protect it from looters. In May and June 2001, Saturno, Graham, Stuart, and several others, working with Guatemalan authorities, returned to evaluate the site and begin preservation. Before leaving, they sealed the tunnel and hired guards to keep away looters.

The site is a large complex that was probably occupied from 400 B.C. to 400 A.D. Saturno said, from the mid-Preclassic Period to the mid-Classic Period. The Classic Period began in 250 A.D. and ended with the Maya’s abrupt decline around 900 A.D.

The spot where the mural was found appears to have been occupied during five different building phases, Saturno said. The most obvious structure, the pyramid, dates from the early classic period, several hundred years later than the building in which the mural was found. Following traditional Maya building practices, the pyramid was built right on top of the older structures.

Little is known about the building in which the mural was found, Saturno said, including its overall dimensions. He only knows its width – about 12 feet – because the looters tunneled through both walls. The uncovered section of the mural is about four feet, but researchers believe it wraps around the whole room.

Unlike the 1946 Bonampak mural, whose subject is historical battles, this mural appears to depict Maya mythology, as the little that is exposed shows gods and goddesses in some kind of ceremony.

Though researchers are eager to see the entire mural and find out what it tells of Mayan culture during the time it was painted, unearthing it will be a painstaking process lasting as long as five years, Stuart said. Great care must be taken so the pigment painted onto the smooth plaster walls doesn’t come off as the dirt is removed.

“The thing about this that is so exciting is the potential,” Stuart said. “We don’t know what’s there.”

Wrong place, right time

Ironically, Saturno wasn’t supposed to be near San Bartolo at all. When he arrived in Guatemala, his guides had overbooked and couldn’t take the longer trip to two known sites where he planned to catalog carved hieroglyphics. In consolation, the company offered to provide guides to San Bartolo, a closer site in an uninhabited part of northeastern Guatemala that was unknown to archaeologists. The guides thought they’d be able to visit San Bartolo and return in a day.

San Bartolo is in northeastern Guatemala, in an area called Peten, which was fairly thickly settled during the Maya’s Preclassic Period but which is largely uninhabited jungle today. The site itself lies roughly 50 miles from the nearest settlement, amidst jungle dotted with many unexplored ruins.

The Maya lived in a series of city-states centered on the Yucatan Peninsula and ranging from southern Mexico to northern Honduras. They had an advanced civilization, developed a writing system, crafted many works of art, and practiced elaborate religious beliefs.

Trouble plagued Saturno’s trip from the start. What was supposed to be a three-hour Land Rover ride turned into a daylong excursion, as recent logging had left numerous trees across the road. At each fallen tree, Saturno and his guides had to get out and chop a path around before they could continue. It was getting late by the time they reached the footpath to the site and they decided to stay the night on the road.

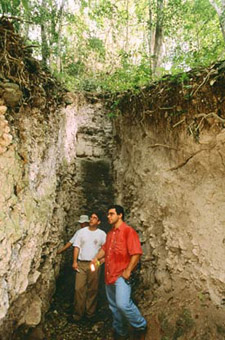

They set off the next morning, expecting at two-and-a-half-hour, six-kilometer hike. Instead, they trekked eight-and-a-half hours in temperatures between 90 and 100 degrees, covering 20 kilometers before reaching the ruins. They were out of water and Saturno’s patience was wearing thin when they finally saw San Bartolo, marred by trenches dug by looters in search of artifacts to sell.

Saturno said he found the mural in a deep trench that looters had dug into the base of an 80-foot-tall pyramid. The trench got deeper as it neared the pyramid, eventually becoming a tunnel. Following typical Mayan building practices, the Maya had constructed the pyramid directly on top of earlier buildings. They probably removed the roof of the building holding the mural and filled it with debris before beginning the new construction, according to Stuart.

It was in one of these earlier buildings, buried beneath the pyramid, that the mural was found.

When the looters’ tunnel reached the buried building, they dug right through one wall and out the other side, continuing beneath the pyramid, seeking a burial chamber or caches of other treasures, particularly Classic era pottery.

“They were just digging away,” Saturno said. “They didn’t find what they wanted.”

Hiking home

Saturno’s discovery turned what would have been a minor failure into a major success. But first he and his guides had to get out of the jungle.

They spent the night at San Bartolo and left the next morning – the excursion’s third day. Having packed for a day trip, they marched on emergency rations of water drained from jungle vines and packets of powdered soup. Saturno and three of his five guides each passed out from exhaustion at some point during the 20-kilometer trek back to the dirt road where their Land Rover was parked.

When he got out, sick from dehydration, Saturno admits his first thoughts weren’t of science, they were of food and water.

“It was not a pleasant walk. I knew this [discovery] had made the trip worthwhile, but when I did get out my only concern was food and water,” Saturno said.

Saturno was sick enough to head for home, leaving a note for Stuart, who was visiting another site in Guatemala, at the house the project used for headquarters. Stuart missed Saturno by three hours.

The note, Stuart said, described the trip and ended with an enigmatic understatement: “By the way, Dave, I found some cool murals.”