Exploring a various, vibrant ‘Harlemworld’

In Harlem, Jackson finds poverty, yuppies, and identity crises

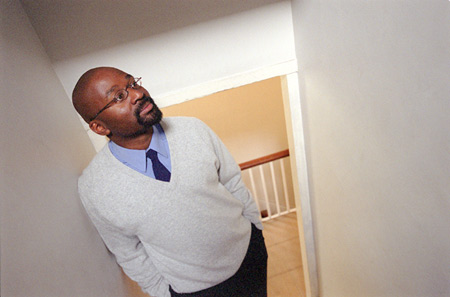

Some anthropologists travel thousands of miles to reach their fieldwork sites. John L. Jackson Jr. traveled a few blocks to reach his, but its proximity didn’t make gathering or interpreting the data any less challenging. As a Ph.D. candidate at Columbia University, Jackson conducted his fieldwork in Harlem, just uptown from Columbia’s main campus.

Harlem, which has been called “the capital of Black America,” is a diverse and complex place, he discovered, a place with such intense awareness of its own historical and cultural significance that when Jackson rewrote his dissertation and published it as a book, he gave it a title that would reflect the neighborhood’s far-reaching reputation: “Harlemworld: Doing Race and Class in Contemporary Black America” (University of Chicago Press, 2001).

Jackson, now a junior fellow in Harvard’s Society of Fellows, and a filmmaker as well as an urban ethnographer, grew up in the Brooklyn neighborhood of Canarsie and saw Harlem only during visits to relatives across the river. Canarsie and Harlem, he said, “are different planets.” He chose the Manhattan neighborhood as the subject of his research because it was “an opportunity to get to know a place that I felt I should know.”

Discovering the truth about Harlem was a long, slow process. Despite moving to an apartment on 125th Street, Harlem’s main drag, Jackson reveals in the book’s preface that he was too shy at first to talk to any of his neighbors. His break came when the city forced a group of open-air vendors off the streets and the protest meetings and demonstrations that ensued gave Jackson a chance to talk to residents about their personal and political views.

What Jackson found was that while Harlem’s racial composition is predominantly African American, its class affiliations span the gamut from the desperately poor to upwardly mobile professionals.

While many social scientists assume that the gap between the black middle class and underclass is marked by alienation and hostility, Jackson found that, in Harlem at least, many people have affiliations that stretch across classes. Class and even race, he discovered, are not so much assigned categories as performances, based on variations in speech, dress, and physical gestures.

Jackson’s many interviews with Harlem residents bring out the subtle distinctions within these codes of behavior. For example, some social scientists have explained academic underachievement by black youth as the result of intelligence being stigmatized as “acting white.”

Many of Jackson’s informants, however, clearly see the value of education. What they object to are “microbehaviors” that signify an individual’s racial disloyalty. A high school student named Timothy, for example, expresses an enthusiastic love of learning originally inculcated by his mother. When Jackson asks if anyone ever accused him of acting white, he replies: “Not to my face. They’d have had a problem. I can show somebody black if they want to see it, but they better want to see it.”

Other middle-class blacks solve the problem of multiple class allegiances by keeping their friends separate. Paul, an architect earning a six-figure income, has two separate birthday parties, one with his old neighborhood buddies in Bedford-Stuyvesant, the other with his professional friends in Harlem.

Others maintain ties across class lines even though relationships may be strained. Cynthia, a college-educated office manager, stays in touch with her old high school friend Karen, a single mother with a history of drug abuse and prostitution, even though Karen’s present condition is extremely disturbing to her.

The expanding economy of the 1990s, the establishment of empowerment zones, and the arrival of businesses like Blockbuster Video, Old Navy, and the Disney Store were in large part responsible for the signs of economic renewal that Jackson observed during his years of participant-observation in Harlem. But the sense of hope that informs his analysis of this complex community is based on more than material prosperity.

For Jackson, the chorus of voices he has recorded, voices from all points on the socioeconomic spectrum, commenting in their own way about race and class, about black-white relations, the problems of the workplace, the behavior of politicians, the ravages of drugs, and a host of other topics, “constitute the ground floor of antiracist folk analyses of identity.”

By seeing race and class as something people “do” rather than as fixed identities, Jackson’s informants contribute to the undoing of stereotypes by challenging the constructions that others impose on them. Jackson’s research convinces him that this ultimately salutary process of grassroots deconstruction goes on continually in Harlem and in communities around the world.

While writing “Harlemworld,” Jackson has been busy with other projects that employ the medium of film as a way of exploring and interpreting human behavior. His interest in filmmaking actually predates his study of anthropology. He decided to become an anthropologist, in fact, because he thought it would provide him with subject matter for making films, and the two pursuits have continued to cross-fertilize one another.

“As an anthropologist, filmmaking has been an anchor for me. It’s only because I do both that I’m able to do anything at all. I was really lucky to choose a discipline where film is important.”

One of Jackson’s film projects explores the effect of gentrification on the lives of Harlem residents. Another, which he is doing in collaboration with Vincent Winbush, a theologian at Union Theological Seminary, examines the role of the Bible in the lives of African Americans around the country. A third project looks at charismatic leaders of black religious cults.

“I want to push the limits of filmmaking, and also of anthropology, maybe use one to ask questions of the other,” Jackson said. “I think that cameras are good tools to think with.”