Girls can look up to ‘A Hero for Daisy’

When Mary Mazzio decided to make a career shift from corporate lawyer to independent filmmaker, her goal was to produce movies about remarkable women.

When Mary Mazzio decided to make a career shift from corporate lawyer to independent filmmaker, her goal was to produce movies about remarkable women.

Certainly, her first film, “A Hero for Daisy,” shown May 7 at the Graduate School of Education (GSE), amply meets that objective.

The film profiles Chris Ernst, a two-time Olympic rower who left in her wake not only rival boats but inequalities and gender stereotypes as well.

Set to a rousing musical score that runs the gamut from Aaron Copland to Annie Lennox, the film tells Ernst’s story through interviews and action footage, painting a portrait of a woman who, rather than conform to the world’s expectations, has forced it to conform to hers.

Ernst enrolled at Yale in the early 1970s, shortly after the school went co-ed, and promptly joined the newly formed women’s rowing team. The women did well in competition, winning more races than the men’s team, but the respect and consideration with which they were treated were not commensurate with their performance

The worst indignity was that the school refused to give the women their own locker room at the boathouse, a 30-minute drive from the main campus. While the men showered and changed into dry clothes, the women waited on the bus, shivering in their sweat-soaked workout gear, their hair freezing to their heads.

There was an up-side to this humiliation, however, as one of Ernst’s team members points out in the film. While they waited on the bus the women had time – and motivation – to plan and strategize.

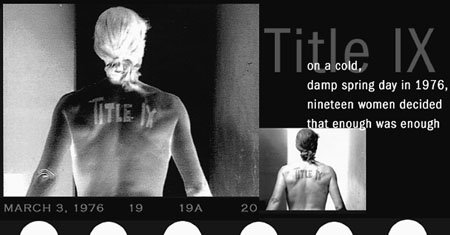

After the Yale athletics department consistently turned a deaf ear to their requests for better facilities, the women, led by Ernst, hatched a daring plan. Accompanied by a New York Times reporter, they marched into the office of the director of athletic facilities and, at a given signal, removed their sweatshirts. Across the chest and back of each of the 19 women was written the phrase “Title IX,” the federal legislation mandating that schools spend the same amount on women’s athletics as for men’s. The story was carried by newspapers all over the world, and within weeks the women had their own locker room.

“We learned that embarrassment is a wonderful thing,” says Ernst, who now owns her own plumbing company in Brookline. “They were pretending we weren’t there, and our protest was saying, ‘Here we are!’”

Ernst has continued to announce her presence in this same forthright and emphatic fashion, an attribute that the film both portrays and celebrates. Sen. John Kerry, a fellow Yale graduate and one of the film’s interviewees, compares Ernst with Rosa Parks in terms of the catalytic effect she has had on women’s athletics.

Mazio, who was herself a member of the 1992 Olympic women’s rowing team, participated in a panel discussion after the film. Also on the panel were Carol Gilligan, the Patricia Albjerg Graham Professor of Gender Studies, and Mary Jo Kane, director of the Tucker Center for Research on Girls and Women in Sports at the University of Minnesota.

Mazzio explained that she chose Ernst as the subject of her first film because of the impact Ernst had on her own life. Impressed by the strength and determination Ernst displayed in the gym, Mazzio asked if she could work out with her.

Ernst agreed, but made Mazzio promise to “never cheat in practice, and when you race, take every advantage.”

Mazzio said that her meeting with Ernst was a turning point in her life. “She taught me how to commit and to have the courage to fail.”

The idea for the film came to Mazzio when she was pregnant with her now 3-year-old daughter, the “Daisy” of the film’s title. She was watching television when a Victoria’s Secret commercial came on, peopled by supermodels with perfect, long-legged bodies.

“I thought, all these women are fabulous and gorgeous, but, my God! Eat something! It made me feel there was nothing out there for my unborn daughter, nothing that told her she could be strong, be ugly, be dirty, and say what she needs to say.”

Kane added that Title IX has had an enormous and salutary effect on women’s athletics.

“In one generation, we have gone from a situation where young girls hoped there was a team to a situation where young girls hope they make the team. That wouldn’t have happened if not for Title IX.”