Ancient script rewrites history

‘This is like the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls’

Near a river in Guodian, China, not far from a farmhouse made of earth and thatched with straw, Chinese archaeologists in 1993 discovered a tomb dating back to the fourth century B.C.

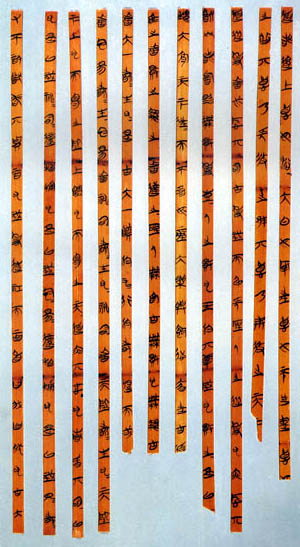

The tomb was just slightly larger than the coffin and stone sarcophagus within. Scattered on the floor were bamboo strips, wide as a pencil, and up to twice as long. On closer scrutiny, scholars realized they had found something remarkable.

“This is like the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls,” says Tu Weiming, director of the Harvard Yenching Institute (HYI), who has played a key role in the preservation of, accessibility to, and research on the Guodian materials since 1996.

The 800 bamboo strips bear roughly 10,000 Chinese characters; approximately one-tenth of those characters comprise part of the oldest extant version of the Tao Te Ching (also known as Daodejing), a foundational text by the Taoist philosopher Laozi, who lived in the sixth century B.C. and is generally considered the teacher of Confucius. The remaining nine-tenths of the writings appear to be written by Confucian disciples, including Confucius’ grandson Zisi, in the first generation after Confucius’ death. (Confucius lived from 551 to 479 B.C.) These texts amplify scholars’ understanding of how the Confucian philosophical tradition evolved between Confucius’ time and that of Mencius, a key Confucian thinker who lived in the third century B.C.

“With the discovery of these texts, I think you can say that the history of Confucianism itself will have to be rewritten,” says Tu. “And by implication, the history of ancient Chinese philosophy in general will have to be reconfigured.”

Shortly after their rediscovery, the 2,000-year-old strips were immersed in solvents to restore the faded writing. “They became so brilliant, as if the characters were written yesterday,” said Tu. The length of the strips, their content, and special markings, like bands on a bird leg, helped scholars sequence the strips.

With scholars such as Sarah Allen, a sinologist at Dartmouth College; Harvard scholars Michael Puett, Susan Weld, and Feng Yu; and others at Wuhan University and Beijing University, HYI began working in 1994 to ensure the texts’ accessibility to scholars and the widest possible international exchange of ideas. The Institute helped sponsor an international conference at Wuhan University in 1999, and has overseen three Chinese publications devoted to the Guodian manuscripts. It has also participated in the development of a Chinese language Web site, http://www.bamboosilk.org, devoted to the Guodian texts. Professors Wang Bo and Guo Yi, from Beijing University and the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, specialize in the Guodian manuscripts and are visiting scholars at HYI this year.

Image of the human heart

What do the bamboo strips tell us?

These texts radically alter scholars’ understanding of not just the principles of, and relationship between, Taoism and Confucianism, two major streams of Chinese thought; they affect our understanding of Chinese philology, and reopen debate on the historical identities of Confucius and Laozi.

Taoism was previously considered a critique of Confucianism, says Tu. With the discovery of the Guodian texts, the two schools can now be seen as more complementary than formerly imagined.

“From the Confucian point of view, human beings are sociological animals,” says Tu. “They are psychological, political, poetic – meaning aesthetic – but also metaphysical.” Confucians advocate “engagement in the world, social service, critique of the political order, and the idea of personal self-cultivation as the basis for social transformation.” Taoists, in contrast, “would like to reject the sociological, political aspects of the human, focusing on the ‘natural way,’ following nature, against any kind of human, artificial intervention in the natural process.” Taoists refer to the “way of heaven” as a guide for human behavior.

The Guodian version of the Tao Te Ching reveals far more tolerant views toward Confucian ideology than previously seen. Moreover, the Confucian texts in the Guodian cache reveal a more complex worldview than traditionally understood.

For years scholars believed that Confucians were little concerned with human emotions. But in the Guodian texts, the element “xin,” – a pictographic image of the human heart – appears over and over again as part of several Chinese characters. It’s a startling display, both philologically, in terms of understanding the evolution of Chinese characters, and philosophically. “These texts conclusively show that emotions or feelings as we understand them today were major philosophical concerns,” Tu says. The Guodian texts offer detailed descriptions of a range of human emotions. They also extensively explore the relation between heart, mind, and human nature; between the inner self and the outer world; and whether human nature is good or evil – a cumulative emphasis on the inner dimensions of man that most scholars formerly believed came much later in Chinese intellectual history.

A cosmic shift

Simultaneously, Confucian views on man’s relation to the polity require reinterpretation in the wake of the Guodian discovery. These early writings reveal a “spirit of protest,” in Tu’s words, a definition of a loyal minister, for instance, as he who consistently criticizes his emperor. This priority on the people’s agenda, with the ruler’s views secondary to their concerns, has long been ascribed to the thinker Mencius; now scholars see much earlier roots, in Zisi, for this notion of government.

Indeed, a powerful school of thought in modern China, the “Doubting Antiquity” school, has been seriously discredited in the wake of these discoveries. “This is the most important school of interpreting Chinese classics,” Tu says. Its advocates have not only attempted to date as much later, or even doubt the existence of, ideas we now know took root in earlier times; they have called into question the role of Confucius and his disciples in forming what we consider Confucian philosophy. The Guodian texts, by providing evidence of regional Confucian thinkers close to the time of the philosopher’s presumed existence, help restore this intellectual lineage.

The genealogy of Chinese intellectual thought is now undergoing revision and Taoist and Confucian texts are being reinterpreted. And because Taoism and Confucianism are very much “living traditions” in China, these slender bamboo strips have the potential to transform daily living. “These are not simply philosophical ideas; they have broad implications for practical living, for the development of polity and society,” says Tu.

Some of the Taoist Guodian texts offer a whole new cosmology – a view of the creation of the universe with elements not even mentioned in later versions of the Tao Te Ching: the creation of water, the existence of four seasons, the birth of heaven and earth after other events have taken place. The bamboo slips themselves are having a similar effect on the Chinese intellectual universe.

Brave new world.

Contact Andrea Shen at andrea_shen@harvard.edu