Requiem for sax and canvas — Carpenter Center project commemorates a friend

Think of one of the great churches of Europe St. Peters in Rome or Englands Canterbury Cathedral a place of great beauty and solemnity filled with monuments to the illustrious dead, its lofty nave reverberating with sweet voices or the thunderous tones of an organ.

Jazz musician Marty Ehrlich and visual artist Oliver Jackson are working to create a similar sense of sacred space, dedicated not to the memory of a great prince or churchman, but to their friend, jazz musician and composer Julius Hemphill, who died five years ago of complications resulting from diabetes. The space they plan to honor with music and imagery is not a church or chapel but a gallery in the Carpenter Center.

“The great cathedrals, the Medicis tomb, the Jewish temple on the High Holy days, theyve all carried out the idea of a memorial space very well,” Jackson says. Voluble and enthusiastic, Jackson speaks about his current project while using a long-handled paint roller to apply white acrylic undercoat to a huge canvas taped to the floor of his Somerville studio.

“It appears that people are more profoundly moved by aesthetic experience when its part of the making of place than when its in isolation. Thats not a new idea, but its fallen out of currency.”

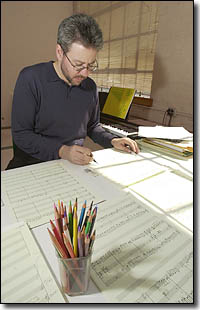

Jacksons residency at Harvard is supported by the Fogg Art Museum, while Ehrlich, working at his electronic keyboard in an adjoining space, is supported by a fellowship from the Office of the Arts.

“Its been challenging to look at things from the angle of whats unique and whats shared between the two arts,” says Ehrlich, a saxophone player and composer who played with Hemphill on many recordings and now leads several of his own groups, including the Dark Woods Ensemble.

“This project is also a continuation of a long-term dialogue Ive had with Oliver about music, art, life. Weve been friends since the early 80s. Ive got the phone bills to prove it.”

In the late 1960s, Hemphill was a founding member of the Black Artists Group in St. Louis, a group comprising musicians, dancers, actors, painters, and writers. An eighth-grader at the time, Ehrlich took a theatre class from one of the groups members, met Hemphill, and got hooked on jazz. He went on to study at the New England Conservatory, then embarked on a career as a jazz musician.

Hemphill, meanwhile, had achieved prominence as a member of the strikingly original World Saxophone Quartet. Ehrlich first played with him as a member of the Julius Hemphill Big Band in 1982 and later participated in several Hemphill-led small groups. Ehrlich has since dedicated himself to keeping Hemphills music alive.

Oliver Jackson met Hemphill in the 1960s when he attended one of the latters St. Louis concerts and then stuck around to tell the musician how moved he had been by his performance. A relationship began that combined friendship with artistic collaboration.

“We did projects together, and we talked about the arts. He was an extraordinary musician and composer, but really the relationship was based on the fact that we liked each other.”

The relationship was based on mutual admiration, as well. Hemphill used Jacksons artwork on his album covers. It was a Jackson drawing selected by Hemphill for his 1977 album Blue Boyé that first brought the artist to the attention of an undergraduate named Harry Cooper 82, currently the Fogg Art Museums Associate Curator of Modern Art and a self-described “huge jazz fan.”

Cooper, who worked as a disk jockey on WHRBs Jazz Spectrum during his undergraduate years, kept his eye on Jacksons career and noted his association with Ehrlich as well as with Hemphill. Finally, at a 1998 concert Ehrlich played in New York, Cooper got the chance to talk to him about Jackson. He learned that the two were not only friends but had been wanting to work together on a multimedia project.

Cooper began to explore ways in which he could make that happen. At the same time, he tried to find ways to support both artists during their collaboration, a search that brought him to Cathy McCormick, director of programs at the Office for the Arts. The ensuing discussions eventually led to the Harvard Jazz Bands April 8 concert at Sanders Theatre, “A Tribute to St. Louis Composers,” with Ehrlich as guest artist, as well as to the saxophonists Office of the Arts-sponsored residency as the 1999-2000 Peter Ivers Visiting Artist.

Coopers efforts to find support for Jackson not only made the collaboration with Ehrlich possible, but also, with the support of James Cuno, the Art Museums’ director, resulted in a loan to the Fogg of three canvases the artist did in the mid-1980s. These will remain on display until June 18th.

Cooper has long been an ardent and knowledgeable admirer of Jacksons work.

“I think he is one of the major painters working today, although there are many who havent heard of him,” Cooper said.

He describes Jackson as something of an outsider who stubbornly adheres to Modernist rather than contemporary theories of art-making, typically filling his canvases with overlapping human figures that seem to float in indeterminate space. Jackson, who has taught at California State University since 1971, currently has a major exhibition of his work at the Fresno Art Museum.

For the collaboration with Ehrlich, Jackson has created six huge canvases (about 9 by 10 feet) that he plans to combine with sculptures and other objects. These works will be placed in a specially designed space in the renovated Sert Gallery in the Carpenter Center.

For his part, Ehrlich has composed three hours of music which he will record both by himself and with seven other musicians. The individual segments vary from three seconds to five minutes in length, and there is a generous use of silences. There will be two distinct spaces in the exhibition, each with its own speaker system. Sometimes the same music will play in both spaces. At other times different music will play simultaneously.

“Im trying to use my whole palette of writing,” Ehrlich said. “The idea is to create a sort of garden where the different elements interact so the person will be drawn into a resonant relationship with both music and painting.”

“Were not trying to describe Julius [Hemphill],” added Jackson. “Some people know Julius music and some dont. Were trying to create an homage to him, something that has a particular ambience, a character, that enables people to step into a certain feeling zone.”

The exhibition is scheduled to open in the Sert Gallery in the fall of 2001.