Cataloging Terror — Makiya and team lead effort to index Iraqi atrocities

It was one of the most horrific episodes in recent world history. Almost 400 villages in Northern Iraq were eliminated in 1987 and 88 with thousands of inhabitants allegedly murdered ???? and much of it is documented in top-secret military and security papers pilfered from the Iraqi government in the closing days of the Gulf War.

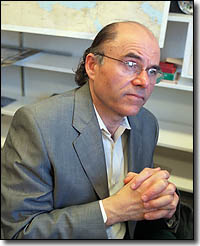

Copies of those papers, nabbed by Kurdish groups and given to the United States government almost 10 years ago, are now in the hands of a team of experts at the Center for Middle Eastern Studies at Harvard. The team is working to index the documents in order to give history a clearer picture of the inner workings of the Saddam Hussein regime. The Iraq Research and Documentation Project (IRDP) is led by Kanan Makiya, an Iraqi dissident who left his home in Baghdad in 1968 to study at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and never returned. His only visits back have been to the northern sectors of his troubled homeland, in order to facilitate efforts to bring the secret documents to the United States.

In the Belly of the Beast

“I returned to Northern Iraq in the fall of 1991 after I heard that the Kurds had captured large quantities of documents,” Makiya explains. “I was able to confirm [the documents] were very considerable and potentially very valuable.” Eventually the Kurds were convinced to assemble volumes of information from a number of different sources, then turn them over to American authorities, with Makiya obtaining a promise from the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, the body in charge of the documents, that he would eventually receive a copy. “For my purposes, the main interest lies in being able to look at this rather extraordinary regime in Iraq from the inside out from the belly of the beast, so to speak.”

For several years, state department officials and human rights organizations such as Human Rights Watch pored through the documents. Finally, last year, they turned over 17 6 CDs, filled with millions of digitally scanned images, to the Center for Middle Eastern Studies. Thats when Makiya went to work securing funding and forming a five-person team to help design and run the software necessary to sort through and index the information, and then develop a comprehensive, multimedia Website (www.fas.harvard.edu/~irdp) that will allow others to access the documents. Operators are now indexing the material page by page. “On average, we can do 30 to 40 pages an hour,” Makiya says. “The target is to have covered between 60,000 and 100,000 pages by the end of October. That would give us a sampling, a small feel for the potential utility of the material.”

The reams of material reviewed so far have not contained any major surprises, but Makiya is not disappointed. “My argument has been all along that you dont go around looking for a smoking guns in these documents so the hypothesis is you really need to make the archive accessible for searches in order to understand patterns, structures, and relationships.” The slow and laborious nature of the work can be rather tedious, Makiya admits, and “the story the documents have to tell by themselves is yet to be fully explored,” but he is confident that the result will be a “searchable database [that will] cast light on how this regime worked, especially in the 1980s, the period covered by the documents.”

According to Makiya, Saddam Husseins regime operated by perpetuating “a pervasive atmosphere of suspicion and distrust which eventually leads to a breakdown in the moral fiber of the country.” Even more significantly, Makiya says, is the overall feeling, through all social classes, that “hope itself has been killed.” Many of the documents that Makiyas team are now examining seem to affirm that belief in particular those focusing on the Iraqi governments crackdown against the Kurds in Northern Iraq in the late 1980s. During that time, Hussein launched what is known as the “Anfal Operation,” aimed at eliminating the Kurds from certain parts of Kurdistan. Makiya says the documents detail how the operation began with a relocation program, then evolved into the systematic removal and disappearance of thousands of men, women, and children, and the subsequent destruction of several hundred villages that they left behind.

Casting a “sharp, bright light”

The Anfal Operation, and others like it, were, according to Makiya, the most egregious examples of human rights abuses in Iraq, but the IRDP is focusing more on the deeper sociological factors at play in the country. “A lot has been written about how nasty this regime was, but one wants to go further into what made it work what kept it going for so long and why its still there . Casting that kind of a sharp, bright light on this kind of dark world that was never meant to be seen by anybody is potentially very exciting.” When the exhaustive cataloging is complete, Makiya believes, the database created at the Center will become “a permanent part of the [collective] memory of what happened. We want to make sure that people will never forget” what Hussein did to Iraq.

For now, Makiya is focusing on securing additional funding to complete the project at Harvard. He is also hoping to expand the scope of the IRDPs purview, so that it can begin collecting and analyzing other documents relating to Saddam Husseins power structure and his hold over the Iraqi people. “What we hope to do by proving ourselves is to become a collecting house for these other sources of documents If this method works, we will have created a system for categorizing and studying this.” For now, the method seems to be working as designed, and day by day, page by page, word by word, Makiyas team is building a vitally significant database that will serve historians and scholars for centu ries to come.