Love Is in the … Computer

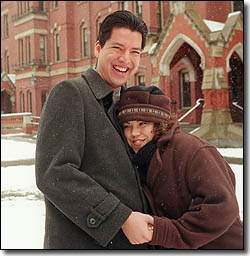

It was a crowded room, but the eyes of Ana Tavares and Fidencio Saldana did not meet across it. That is because Saldana is 6-foot-5 and Tavares is about a foot shorter.

“It was more eyes to chest,” Tavares said.

Fortunately, Saldana’s chest was adorned with a name tag, which not only allowed Tavares to learn who he was but also that they were destined to be together, at least according to the computer that had processed their personal facts and preferences. What neither of them suspected was that the computer was right.

The scene was Club Joy, a small night spot on Washington Street in Boston. The occasion: the 1999 Valentine’s Day dance for Harvard graduate students. Saldana, 26, a student at the Medical School, and Tavares, 28, a student at the School of Education, had both been dragged there by their friends.

They had also been persuaded to do something that each of them considered even sillier and more pointless than spending several hours at a dance where the floor was too packed for dancing — fill out a questionnaire for a computer match-making service.

For $5 each participant would receive a printout of his or her 10 most compatible matches. The service had been organized by Lorien Abroms, a student at the School of Public Health (SPH) and a member of the Harvard Graduate Council. Revenues from the project benefited the public service organization City Year.

The two quickly discovered that they were on each other’s lists. They also discovered that they shared a Latino heritage (Saldana is a Mexican American from California, Tavares a Dominican American from New Jersey) and soon they were conversing in Spanish. Then, after promising to get in touch by e-mail, they left with their respective groups of friends.

A lively e-mail correspondence developed shortly afterward.

“He was really funny,” Tavares said. “I think he was sleep-deprived.”

“That’s probably true,” said Saldana, who was in his third year of medical school at the time. “I was in the middle of a very difficult rotation. She caught me at my worst.”

The two also began meeting for coffee and other activities, but neither felt that they were dating. They were just friends who enjoyed each other’s company.

Things changed when Tavares invited Saldana to her graduation in June. At a special dinner that evening the couple danced for the first time, and there was magic.

“You know how sometimes when you dance with someone it just feels fantastic?” Saldana said.

Tavares’ father picked up on the feelings between them. After graduation, Tavares drove with her parents to their home in Florida. In response to his questions about Saldana, she gave her father her stock answer that he was just a good friend, that there was nothing serious between them.

Tavares’ father replied with a Spanish proverb: “El diablo sabe mas por viejo que por diablo,” which means, “The devil knows more because of his great age than because he is the devil.” Very loosely translated, it means, “I wasn’t born yesterday.”

Saldana came to the airport to meet Tavares when she returned to Boston. “That was the first time we kissed,” he said. “After that we started dating in earnest.”

Another milestone was passed that summer when Saldana invited Tavares to his best friend’s wedding. Saldana’s family liked her immediately.

“At one point his mom turned to me and said, “If nothing comes of this, I wish you the best. However, I think my son is the best.”

Saldana popped the question on Dec. 15, 1999. He had made elaborate preparations. With the cooperation of her roommates he filled Tavares’ room with dozens of sunflowers, her favorite. That evening they went to dinner at a romantic restaurant, followed by the ballet The Nutcracker at the Wang Center, followed by coffee and dessert at Cafe Paradisio in Cambridge.

There he presented her with a scrapbook of photos they had taken over the past few months and copies of their e-mails, and he recited a poem that he had written. Later, on a walk through Harvard Square to the spot where they first kissed, he got down on one knee and announced: “Me has hecho el hombre mas feliz del mundo [You have made me the happiest man in the world.] Will you marry me?”

Tavares said yes. Recalling the moment three months later, she commented, “but if someone had told me last year that this would be happening, I would have told them, you must be on drugs!”

Tavares and Saldana are the first couple to become engaged as a result of the Harvard Graduate Council’s computer matchmaking service, but they are one of many couples to find romance and companionship through their participation in the process.

Lorien Abroms, who created the service three years ago, has collected numerous testimonials from satisfied users. Typical is this one from a male student at the Kennedy School: “I met someone I really, really like, and it is going better than I ever dreamed (and I’m a bit of a dreamer!). I’ve decided to stay in Boston after I graduate to give our budding relationship a chance. She could be the one! Thanks for helping me meet her!”

Abroms, whose studies at SPH focus on how social ties affect health, came up with the idea for the service when she realized that there were scarce opportunities for forming relationships in graduate school and that she had the expertise to do something about it.

Having earned a master’s degree in sociology from Brown University, she was familiar with survey techniques. She composed a list of 23 questions that were lighthearted enough so that people would not be bored or intimidated, yet provided enough information about their preferences in such things as religion, politics, music, movies, reading, and food that reliable match-ups could be made.

The first year, she hired a professional programmer to create the software that comes up with the matches, but since then she has had her sister Jessica, a programmer in San Francisco, handle the technical side of things.

Abroms finds this success gratifying not simply because she enjoys playing cupid, but because the positive impact these relationships have on the lives of her customers confirms some of her most deeply held convictions.

“I did this because I feel that meeting people and being connected to people is so incredibly important,” she said.

“Most grad students at Harvard come from all over the world and leave their friends and family behind. Then they set up their lives around their school work, which often gives them a pretty narrow set of people to interact with and in some cases a situation which is not socially nourishing. They are interested in meeting a wider range of people, but it may not happen on its own. This is one more way for grad students — especially grad students at different schools — to meet each other.”

Abroms notes that about 1,000 graduate students use the service each year, one in 12 of all students in the University’s graduate schools.