The Ozark National Forest in Arkansas.

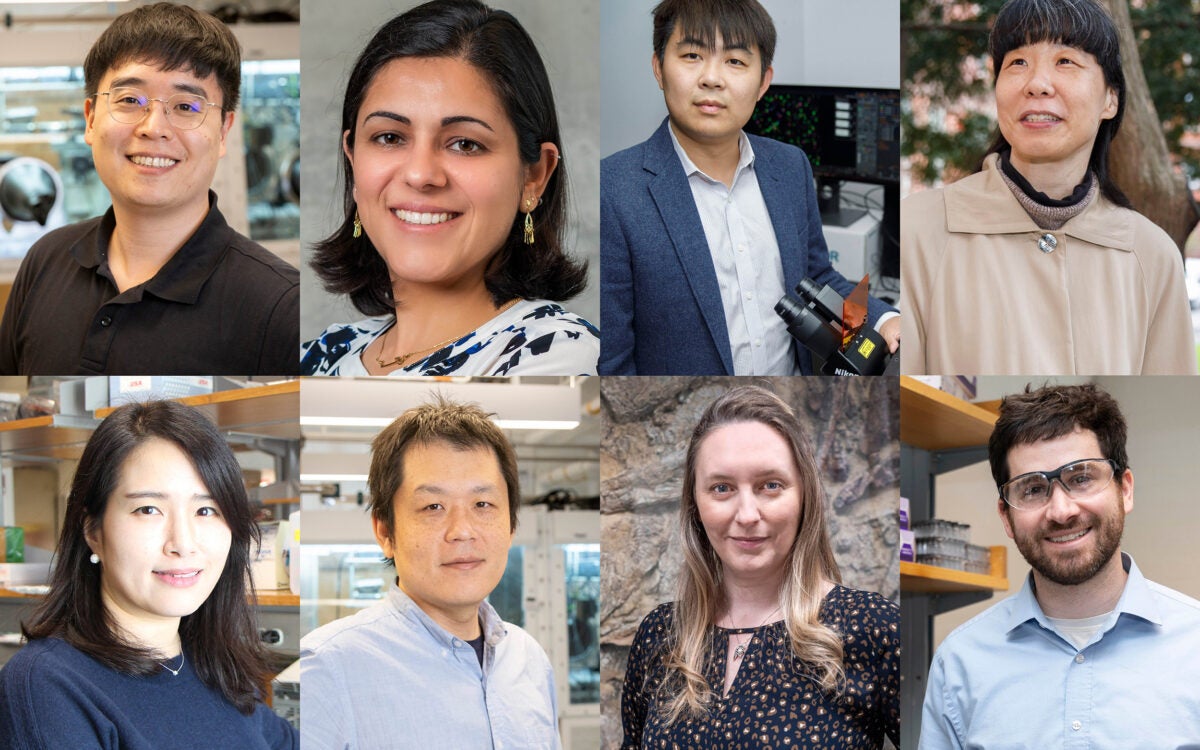

Photos by Tiffany Enzenbacher and Kea Woodruff

Cultivating a wider role for women scientists

An expedition by Arnold Arboretum botanists reaped more than seeds of endangered species

A tiny seed could change the way we experience the natural world. It’s already changed the careers of Tiffany Enzenbacher and Kea Woodruff, who work tending seed in their greenhouses. And it may one day bear fruit in an example of flora rescued from extinction — and a growing space for women in science.

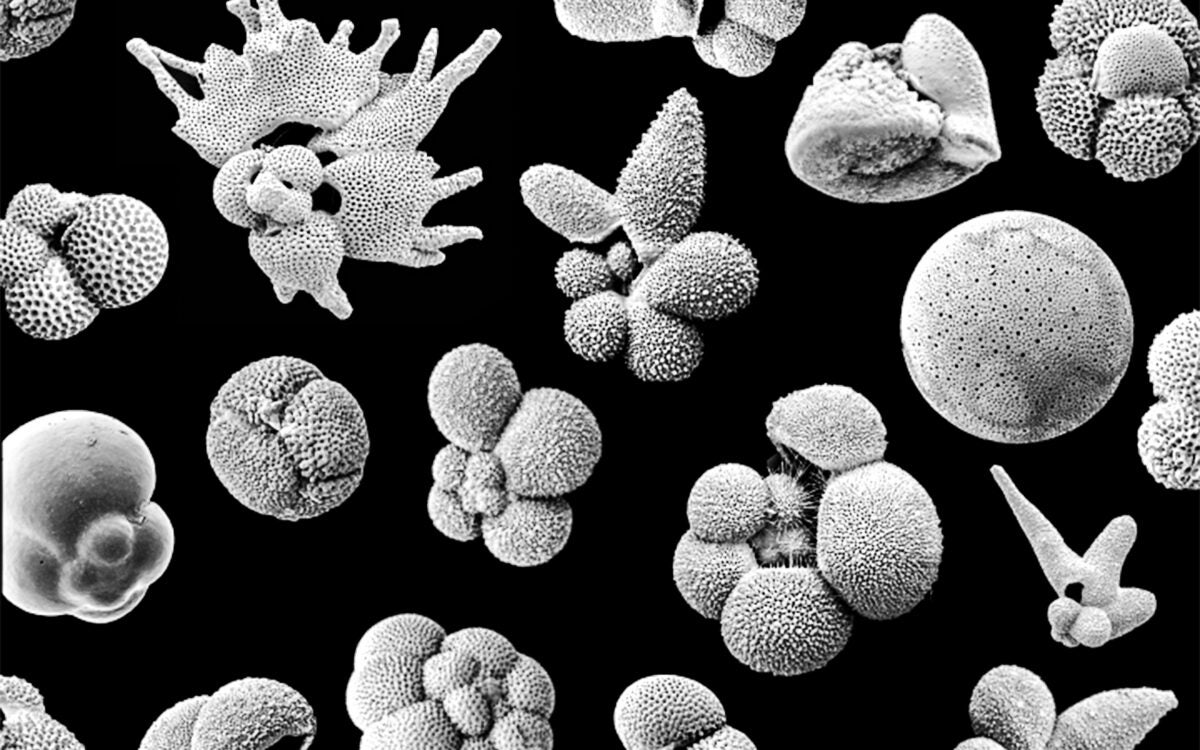

In October, Enzenbacher, manager of plant production, and Woodruff, plant growth facilities manager, left the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University on a road trip to collect seeds of important native species of the American Southwest. In just nine days, they covered more than 1,600 miles through the rugged Ozarks of Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Missouri. The expedition was part of the Campaign for Living Collections, a 10-year initiative to expand the Arboretum’s plant holdings as a hedge against climate change and habitat destruction, which already endanger nearly one in five plant species on Earth.

It was the Arboretum’s third trip to the area, following the 2014 Ozark Exploration and 2017 Arkansas-Missouri Expedition, which yielded 15 of the nearly 400 species on the campaign’s target list. Many of the plants carry conservation status to secure their germplasm for future generations and research. For the latest expedition, Woodruff began the extensive preparations this past spring, working with the Arkansas Natural Heritage Commission, Missouri Department of Conservation, Ozark National Forest, Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation, and local botanists to determine likely locations of specific species.

With their list and collection permits in hand, Woodruff and Enzenbacher mounted daily excursions toting backpacks, data sheets, plant keys, GPS devices, cameras, 10-foot pole pruners, a field press to collect herbarium specimens, and other tools.

More like this

“We are well-prepared for anything that we find, including snakes,” said Enzenbacher. “We both wore snake guards the entire time and also orange vests, as we collected in several natural areas that allow hunting.”

Using GPS coordinates, they hiked several hours each day, referencing their list of plant species and sometimes sampling them. When they found a Diospyros virginiana, or persimmon tree, Woodruff’s was ripe and sweet, Enzenbacher’s hard and bitter. Sometimes they located a target species right away, but other times they walked for hours keeping their eyes on the ground and the sky without result — at least, not the expected one.

“It was exciting to find species that were unexpected. That’s always one of the most fun parts about a trip,” Woodruff said. “You have a list of what you’re hoping to collect, but there is a great amount of visual scanning. Sometimes the plants that you’re not looking for can be more exciting than ones you are.”

Although both women have gone into the field on many occasions, this was their first exclusively female expedition, marking a turning point for both the Arboretum and women in science.

“A hundred years from now, people will see their names embossed as the plant collector on the metal tags at the base of every specimen of dozens and dozens of plants whose passage to the Arboretum began as a seed in their hands,” said William “Ned” Friedman, Arnold Professor of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology and director of the Arboretum. He said their push into the Ozarks “resulted in an extraordinary bounty of new germplasm, including important conservation value material that will eventually enter the living collections on the grounds of the Arboretum.”

Harvard University Library research guides show a sparse history of plant exploration by women. While botany was originally accessible without a formal education, female scientists today are still underrepresented in the field, as well other disciplines. According to a study by the National Science Foundation’s Science & Engineering Labor Force, women constitute just 28 percent of the science and engineering workforce overall. And although Susan Delano McKelvey explored for the Arnold Arboretum more than a century ago, nearly all its collecting teams have been all-male, said Michael Dosmann, the Arboretum’s keeper of living collections.

“How refreshing to see Kea and Tiffany conduct an exclusively female expedition,” he said. “While their wonderful collections will no doubt persist on the Arboretum grounds for decades if not centuries, I believe it is their inspiring example to future women explorer-horticulturists that is most notable.”

Tiffany Enzenbacher catalogs seeds collected during her 1,600-mile trek in the Ozarks with colleague Kea Woodruff.

Photos by Kathleen Dooher

Enzenbacher and Woodruff knew from a young age that working with plants was their calling. Enzenbacher’s great-grandparents started a greenhouse in Des Plaines, Ill., that her extended family still manages. The business ignited her desire to pursue a degree in plant sciences and graduate degree in plant pathology. She manages the Arboretum’s Dana Greenhouses, growing and cultivating 95 percent of the plants that become part of the permanent collections.

The mother of two young girls, Enzenbacher tries to lead by example. She is proud of her job, and said there are many ways to initiate interest in botany. Whether gardening with family or friends, visiting a botanic garden, or asking questions during plant science-focused lessons in school, hands-on work combined with coursework will help build the skills for a career in the field.

“Science can be achieved in so many ways, and when you’ve dedicated your life to this field of plant science, being able to say that anything’s possible is really important,” she said.

Woodruff said what she finds most inspiring about her work is its broad application to many disciplines, including agriculture, ecology, human health, and medicine.

Kea Woodruff collects divisions, or suckers, from this rare shrub in the dry stream bed of Hell Creek in Mountain View, Arkansas. This species of Viburnum was a priority target for the Ozark Expedition this year.

“At the Arboretum we have the opportunity to work with people from so many different disciplines — from biologists, ecologists, geneticists, landscape architects, and horticulturists to historians, artists, parks and recreation managers,” she said. “The most basic requirements to work in this field are only a curiosity about that natural world and a willingness to get your hands dirty.”

Similarly, Woodruff’s family’s work in the logging industry in Washington State led her to pursue a bachelor’s degree in geography and a master’s in forest resources.

“I spent a lot of time in the woods growing up. I loved trees, and I didn’t like seeing so many cut down,” she said. “I went to work in production forestry at the University of Idaho, where my role was to grow trees that were being planted after logging operations. It was very full-circle for me.”

Today she manages the Arboretum’s Weld Hill growth facilities, which utilize state-of-the-art technology to grow plants for research and education.

Both she and Enzenbacher are dedicated to their work in plant collection, curation, and conservation.

“I really enjoy being in this field. What I like most about what I do is collecting, and the whole exploration aspect of it,” Woodruff said. “I can go out there in nature and I have no idea what I’m going to find.”

For a Q&A with Tiffany Enzenbacher and Kea Woodruff, visit the website of the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University.