Ayr Muir, founder and CEO of Clover Food Lab on Massachusetts Avenue in Harvard Square, uncovered old tiles depicting collegiate iconography when renovating the space that his store now occupies.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

Uncovering Harvard Square’s past

Clover store restoration saved glass-covered, tiled school pennants from a century ago

It normally takes one or two days for a demolition team to gut out an old store to prepare it for a new owner, but something stopped one rugged crew in its tracks in Harvard Square earlier this year: tiled walls sporting a Harvard-related motif that dated back a century.

When the team called the new tenant, Ayr Muir, the founder and CEO of the Clover Food Lab, to check out the tiles and see what he wanted to do next, the ready-to-ravage crew was surprised when he said, “We’re going to save them.”

Today the popular vegetarian restaurant at 1326 Massachusetts Ave. offers its customers a rare peek at what a popular downtown Cambridge eatery looked like in 1913. The thoughtful rehab, which features a white tiled floor and walls with decorative crimson H’s and glass-painted school pennants adorning the inside perimeter, also demonstrates how a Harvard grad took on the challenge to restore a small part of the square’s hidden past.

Seated in Harvard Yard, the animated Muir, M.B.A. ’04, said that when the tiles were discovered, the restaurant was about two months away from opening. “How could we open the store in time and still save the tiles, I thought?” Muir said he also considered who would absorb the cost of restoring the tiles, which would require many man-hours to scrape off the layers of accumulated gook. Muir said that he thought about raising the funds from Harvard alumni, but realized that with only weeks to go before the restaurant opened there was not enough time.

Meeting with his general contractor, Muir said a decision was reached to do the tile cleanup work at night with a special restoration team, while the day crew prepared for the store’s opening. He Muir said the expense of the restoration work — about $300,000 — came out of his own pocket. “But it would have been unconscionable to just have let that history disappear. This store has an important story to tell,” Muir said.

Image gallery

MASS AVE 1326 CA 1880

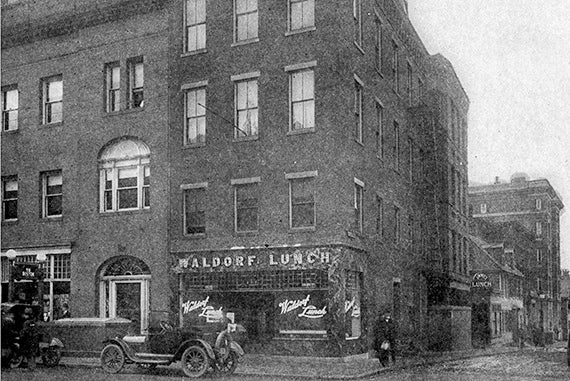

Waldorf Lunch with car in front Credit: 1918 Harvard Class Album, Cambridge Historical Commission

Hayes-Bickfords. Photo ca. 1967 Photo Courtesy of Radcliffe

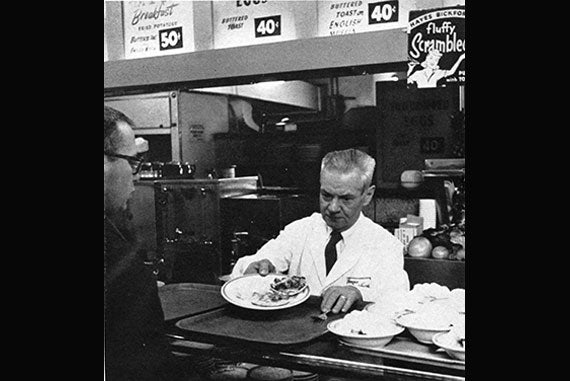

Mass Ave 1326 Hayes-Bick city counterman 1959 Credit: Cambridge Historical Commission

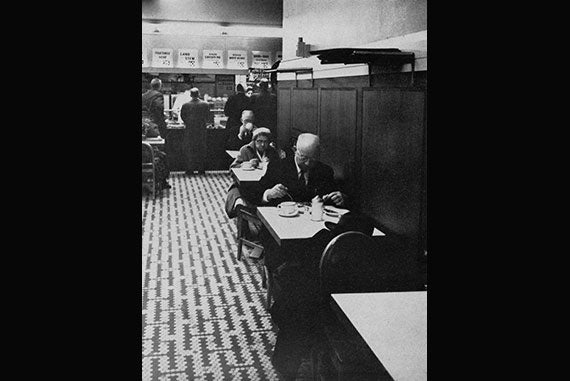

Interiors of Hayes-Bickfords Credit: Cambridge 38, vol. 3, no. 2 (Spring 1959). Cambridge Historical Commission

Clover construction. Photos Spring 2016. Credit: C.M. Sullivan photos. Cambridge Historical Commission

Clover construction. Photos Spring 2016. Credit: C.M. Sullivan photos. Cambridge Historical Commission

Clover construction. Photos Spring 2016. Credit: C.M. Sullivan photos. Cambridge Historical Commission

Ayr Muir, on left, founder, and CEO of Clover Food Lab with employee, Erica Furgiuele, on Massachusetts Avenue in Harvard Square uncovered old tiles when renovating the space that his store now occupies. Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

Part of that story dates back to when Waldorf Lunch, a forerunner of the fast-food restaurant chain, opened its doors at the location in 1913. At its height, Waldorf Lunch had around 200 stores in seven adjacent states. After it closed in the mid-1930s, the Hayes-Bickford, another variant of the quick-service restaurant chain, took over the location until the early 1970s. In 1975, the site became the home of the Chinese restaurant Yenching. Clover took over the lease in 2016.

“The Harvard tiles aren’t new to me,” said Charles Sullivan, M.C.P. ’70, executive director of the Cambridge Historical Commission. Sullivan said that he frequented the Hayes-Bickford in the late 1950s and remembers seeing the Harvard tiled floor. “But nobody at the time had any idea that there was a lot more of those tiles hiding behind those walls,” Sullivan said.

When the tiled walls and school pennants were discovered earlier this year, Sullivan said that his office could only request that Muir preserve the tiles, because the Historical Commission has no jurisdiction over a storefront’s interior. From reviewing old building permits, Sullivan said that his office believes that the tiles were covered up in the 1930s when Hayes-Bickford took over the location. Regardless of when that happened, Sullivan is pleased that they are now uncovered. “The tiles are a treasure for all to enjoy,” he said.

Donna Choih, assistant manager of the Harvard Square Clover store, agrees. “Sometimes we have customers come in just to check out the tiles,” she said. “I’ll ask them if they want to order, and they will say, ‘No, we were just attracted to the interior of the store.’” Choih said that a common question that customers have is whether the tiles are really old or just made to look old. Choih said she assures them that the aged tiles are indeed real.

Fighting to be heard above the lunchtime din, Choih said that many customers are especially drawn to the glass-painted school pennants, which parade such names as Harvard, Yale, Bowdoin, Exeter, and Holy Cross. Choih said that patrons enjoy trying to find their alma maters among the diverse and often unfamiliar mix of names, including the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, a late 19th- and early 20th-century Native American boarding school that often competed successfully against Harvard’s football team.

Considering the larger context of Harvard’s history, Sullivan said the Waldorf Lunch served an important function for Harvard, providing a regular place for students to eat before the House system was constructed. Sullivan said that whereas today Harvard undergraduates eat most of their meals in their House dining halls, in the beginning of the 20th century Harvard undergraduates ate mostly in dining establishments in and around Cambridge, like the Waldorf Lunch. Sullivan and others pointed out that this might help explain why the Waldorf opted for a Harvard-tiled motif, because it would have been welcoming to students. Additionally, the white tiles might have connoted good hygiene, a growing concern.

Finishing up a comprehensive tour of the store, filled with plenty of illuminating historical references and tidbits, Muir finally stopped at a wall facing a bank of pennants. “All these restored pennants are as they looked over 100 years ago,” he said. “Except for one, Boston College, which was pried loose a long time ago.”

Pointing to a pennant on the wall that reads Full Circle, Muir said this was the spot once filled by the Boston College banner. Muir said Full Circle is the name of the small independent school that his parents ran in upstate Massachusetts. Muir said putting the name of his parents’ school up on the wall had nothing to do with restoring a forgotten facet of Harvard or Cambridge’s history, but it was just about “paying respect to the folks.”

Anthony Chiorazzi has an M.Phil. in social anthropology from Oxford University and a master’s degree in theological studies, with a focus on religion and the social sciences, from the Harvard Divinity School.