Strengthening ties among women in physics

Conference connects undergrads in a still-lopsided field

When Margaret Morris looks around her physics class, sometimes she is the only woman there.

Morris, a senior at Brandeis University, is living the reality for physics in the United States. At a time when women make up the majority of the country’s college students, their numbers still trail male peers in certain fields. And in some disciplines, like physics, women remain a small minority.

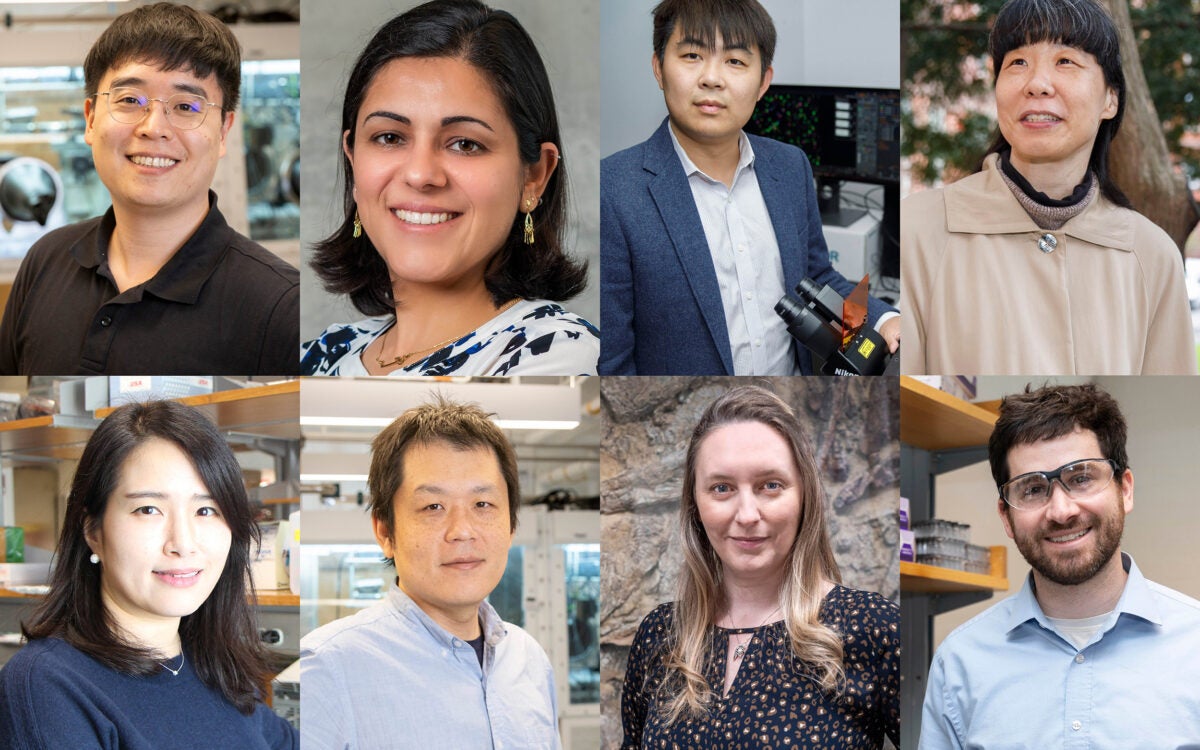

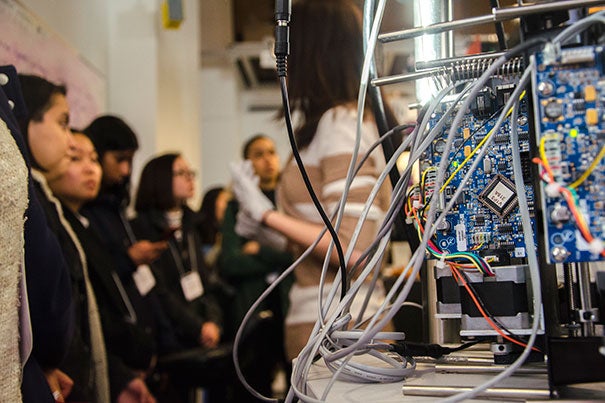

Last weekend, 250 physics majors gathered at Harvard to take a collective step toward a new reality.

The Conference for Undergraduate Women in Physics included lab tours, lectures, personal stories, and practical discussions about research, graduate school applications, how to deal with discrimination and implicit bias, and finding mentors.

Organizer Anne Hebert, a Harvard grad student, said the conference was designed to connect participants with a support network that will help them move ahead in the field.

“As an undergraduate, obviously I noticed there weren’t many girls around,” Hebert said. “Every girl in physics has a moment when they turn their head and realize they’re the only girl in the room.”

One of her fellow organizers, Ellen Klein, a Harvard doctoral student, said that as an undergrad at Yale University, she felt supported by faculty members and never experienced blatant gender discrimination. But she has noticed that there have been fewer women as she’s advanced through different academic levels.

Delilah Gates, also an organizing committee member and Harvard doctoral student, agreed with Klein and Hebert that bias, though often subtle, is still a problem. All three have heard male classmates joke about women and understood in a visceral way that, though real progress has been made, plenty of work remains.

More like this

Gates added that as a black woman, she felt a lot of pressure in college to show that her opportunities weren’t handed to her because of race, leaving her temporarily conflicted about applying to graduate school.

“In college, I kind of didn’t anticipate it. I was struck by the pressure I felt because of being an African-American woman and [proving] that no one was handing it to me because I check off a diversity box,” Gates said.

The campus conference, organized through the American Physical Society, was one of 10 that took place across the United States and Canada and the first to be hosted by Harvard.

Some 1,500 women attended a session somewhere, Hebert said. A workshop titled SPIN UP, for Supporting Inclusion for Underrepresented Peoples, preceded the Harvard conference. The event was aimed at other underrepresented groups in the field, including minorities, students with disabilities, and students from low-income families.

Physics helps solve problems facing humanity, said Masahiro Morii, chair of Harvard’s Physics Department, which provided logistical support for the student-run conference. And, though women make up half the population, they still make up less than 25 percent of physics graduate students.

“Until it’s 50 percent, we’re still wasting a lot of talent that’s out there,” Morii said.