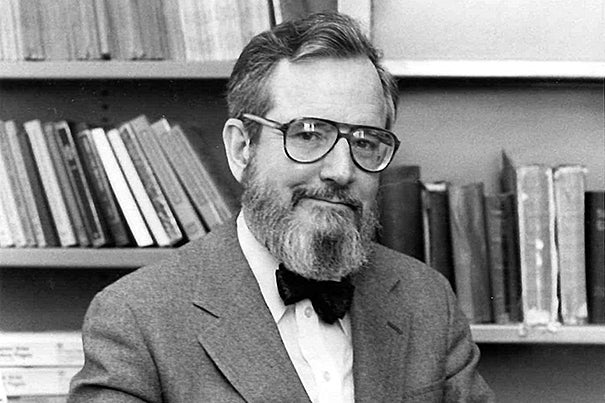

“My students have given me the greatest pleasure,” said Bible scholar Frank Moore Cross, who retired from Harvard in 1992. “I have always had the view that the first task of a scholar is to pass knowledge and understanding of method and the tools of his field from one generation to the next.”

File photo/Harvard Staff Photographer

Frank Moore Cross, 91

A first-rate biblical scholar, but a dedicated teacher first

He traveled the world unearthing and interpreting religious texts from a forgotten time. His nearly 300 academic papers deepened humanity’s understanding of the time and place in which three of the world’s major religions would take root. And yet, over the course of a career that spanned five decades, Frank Moore Cross always returned to the classroom, teaching until his retirement in 1992, and advising more than 100 doctoral dissertations in the process.

“My students have given me the greatest pleasure,” he once told the editor of the Bible Review. “I have always had the view that the first task of a scholar is to pass knowledge and understanding of method and the tools of his field from one generation to the next.”

A world-renowned biblical scholar best known for his work interpreting the Dead Sea Scrolls, Cross died on Oct. 17 in Rochester, N.Y. He was 91. A memorial service will take place Nov. 10 at the Memorial Church.

“He was different from most of the teachers I’d had,” said Jo Ann Hackett, one of his many students turned Harvard colleagues, who now teaches at the University of Texas, Austin. “He would rather teach you how to do something than go in-depth on what it was all about. It meant that when you left, you hadn’t read everything or done everything, but you had the tools to know how to do it.”

Friends and colleagues remembered Cross as a consummate gentleman, with a dry wit and varied interests. He studied ancient texts, yet had a penchant for fast sports coupes. He read and wrote in several “dead” languages, even as he kept his Southern accent. He wore a bow tie to the classroom, and took up backpacking in his 40s, embarking on several long trips through the wilderness with his wife, Betty Anne. A lifelong swimmer, he learned to scuba dive in his 60s so that he could conduct underwater archaeology in the Middle East.

“His interests were incredible,” said Harvard Divinity School Professor Paul D. Hanson. “He was always cultivating some hobby.”

The son and grandson of Presbyterian ministers, Cross’ religious upbringing would guide his career.

“Presbyterians are typically interested in biblical studies and originalism, the idea of what does the Bible say about this or that,” said Lawrence Stager, a Harvard archaeology professor emeritus, and a close friend of Cross. “I’m sure that helped him develop in that direction.”

Raised in Alabama, Cross earned a bachelor’s degree in chemistry and philosophy at Maryville College in Tennessee in 1942. He attended McCormick Theological Seminary in Chicago before going to Johns Hopkins University, where he earned a doctorate in Semitic languages in 1950. His foundation in hard sciences instilled in him a meticulousness that drove his research for the rest of his career.

“He approached much of his scholarship as a scientist,” said List Professor of Jewish Studies Jon D. Levenson, another student of Cross who eventually became a colleague. “He was always interested in the tools used to make an evaluation.”

Arriving at Hopkins shortly after the discovery of a set of ancient scrolls west of the Dead Sea, Cross studied under the legendary Near Eastern scholar William F. Albright, and quickly became one of Albright’s most important pupils. When Albright and his students were given exclusive access to some of the scrolls, Cross was allocated the often fragmented texts of Cave No. 4. In 1958, he published “The Ancient Library of Qumran and Modern Biblical Studies,” a 196-page book that became one of the leading texts about the scrolls and established him at the forefront of his field.

“He had a marvelous way of writing,” said Peter Machinist, a pupil of Cross who is now the Hancock Professor of Hebrew and Other Oriental Languages, which is Harvard’s third-oldest endowed chair, and which Cross occupied until his retirement. “Chiseled prose, I’d call it. He could get into a small number of pages what others would need many more pages to say.”

Cross came to Harvard’s Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations in 1957, having completed stints at Wellesley College and McCormick Seminary. By then, he was making regular trips to the Middle East to see and authenticate scrolls, journeys that often involved arduous plane rides, shoddy communications, and unsavory characters. Work sometimes entailed crawling through caves in 120-degree heat, negotiating with corrupt antiquities dealers, or excavating an archaeological site while bombs went off in the distance.

“It was very cloak-and-dagger,” Machinist said. “Israel was a newly created state, and the whole region precipitated on war.”

In a newspaper article about a trip to Lebanon in 1967, Cross recalled landing in Beirut to procure a collection of newly found scrolls. After proving his identity to an intermediary, he was directed to stand alone on a particular street corner one night, was picked up in a nondescript car, and was driven through the back roads of the city to a mansion where negotiations began. Unfortunately, the transaction fell through when the Arab-Israeli War broke out.

Although the Dead Sea Scrolls remained an integral part of his work, Cross’ publications spanned the field of biblical studies. He was deeply interested in the ancient poetry and history of the Hebrew Bible, and was one of the world’s leading epigraphers.

“I don’t think anyone can command as much as Frank did,” said John “Jay” Ellison, a Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations lecturer who was mentored by Cross when he pursued his doctorate at Harvard. “As the body of knowledge in the field increased, and new texts were discovered, so did his knowledge. He grew with the field.”

Unusually talented when it came to determining the age of a text through the shape of its letters, Cross’ expertise was sought by academics and antiquities dealers around the world. When carbon dating proved the age of a fragment he’d analyzed, he joked that he was happy to have validated the practice of carbon dating.

Despite his prominence, Cross remained accessible to his students. His courses introducing the Hebrew Bible and on the history of the ancient Israelite region became staples for a broad range of undergraduate and graduate students. A demanding instructor, Cross was renowned for demonstrating kindness and treating his students as colleagues.

“He’d often start his lectures saying, ‘As you well know,’ and, of course, you didn’t know,” recalled John Huehnergard, a former student and Harvard colleague, who now teaches at the University of Texas, Austin.

“He had great expectations of his students,” Stager said. “These high expectations drove us to achieve at a higher level than we thought we could.”

That congenial relationship extended to academic work. While studying in Israel in 1966, Stager found a pot shard with writing on it. He took a photograph of it, and eagerly sent it to his professor back at Harvard. Shortly after, a letter arrived from Cross, congratulating Stager on finding his first ostracon.

“I assumed he’d publish a paper on it,” Stager recalled. “Instead, he simply encouraged me to do research and publish on it.”

The pot shard became the subject of Stager’s first published academic article.

“The field is developing, and we still don’t know the full impact of his career,” Stager said. “But he was a great friend, and once he considered you a friend, he was on your side for life.”