A general overview of the 2011 Sendai 8.9 earthquake on Wikipedia. The Japan Sendai Earthquake Data Portal site was built on the model for the China Earthquake Geospatial Research Portal, which is funded by the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies at Harvard University.

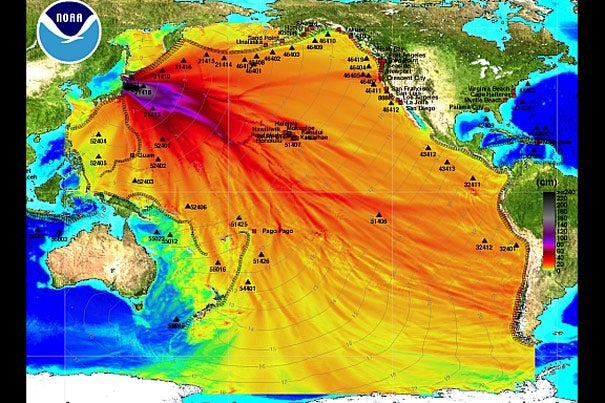

Source: NOAA

A quake data clearinghouse

Harvard center launches web portal to aid response efforts

Within hours of Japan’s disastrous earthquake and tsunami, Harvard’s Center for Geographic Analysis was working to help, creating a web-based portal for information that acts as a clearinghouse for disaster responders and academics alike.

The Japan Sendai Earthquake Data Portal was created by research manager Merrick Lex Berman at the center, based on templates developed in prior earthquakes, the 2008 one in China and last year’s in Haiti and Chile. While it took weeks to create the first site, each subsequent one went live more quickly. For the Japan quake, it took just about an hour to create the site and another hour to begin populating it with data.

The site features a bright orange and blue “energy propagation map” of the Pacific Ocean basin, a map created by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The site includes news feeds from various sources, a link to the main Japanese government disaster web page, and GIS information data sets that connect to geographic information points.

Berman and Wendy Guan, the center’s director of GIS Research Services, said the site is not intended to host all the available information on the quake and tsunami. Instead, it provides some GIS data and links to other useful sites across the web. The site is continuing to add data. Guan sent out an e-mail Friday afternoon seeking geospatial material such as satellite images, aerial photos, GIS data sets, and other files that contain location references. The effort is being sponsored by the Reischauer Institute of Japanese Studies, Guan said.

Guan said she hopes the site will prove useful both for relief workers and for academics seeking to understand the disaster’s impact on their areas of expertise through geographic information. Furthermore, she hopes that those who use the data to conduct analyses will return to the site and post their findings, or links to sites containing them.

“The purpose is to give people a staging platform to share,” Guan said. “They come here to find something useful, and, hopefully, come back when they produce something useful.”

Guan and Berman said each disaster has its own context. In Haiti, volunteer efforts to create, provide, and coordinate data proved critical because little of it existed to begin with, and what did was inaccessible because government offices in Port-au-Prince were devastated by the quake. In Chile and China, the governments remained in control and helped to coordinate relief and the information that guided assistance.

Berman said it is interesting how volunteer efforts over the Internet have altered data flows and responses to such events. Even now, individuals in an array of academic, government, and nonprofit settings around the world are looking at data and producing information and analyses that may prove useful in the emergency response.

For example, Berman said, satellite imagery companies typically produce detailed portraits of disaster zones within a day and provide those images for free to responders. When that data becomes available, Berman said, he will make sure to provide links to it on the portal.