The many aspects of Islamic design

Islamic architecture contains multitudes

Mention the words “European architecture,” and what comes to mind is likely to be a broad survey of periods and styles ranging from the temples of ancient Greece to the latest buildings of Rem Koolhaas or Frank Gehry.

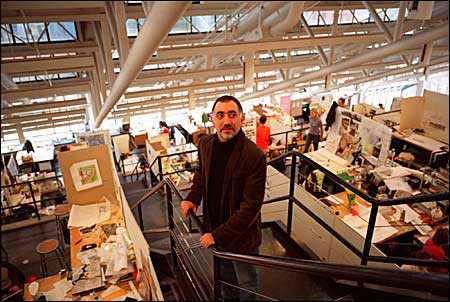

But “Islamic architecture” is apt to evoke a narrower, more stereotypical image, one concocted of pointed arches, shimmering mosaics, and minarets. A. Hashim Sarkis, the Aga Khan Professor of Landscape Architecture and Urbanism in Muslim Societies, wants to change the way we think not only about Islamic architecture, but about design issues in the Muslim world generally.

“I believe we essentialize Islamic architecture too much,” Sarkis said. “There’s always been a perception that the more arches you have, the more authentic the architecture is, but in reality only about 5 percent of the cities in the Muslim world have historic centers dating back to the 12th century, and those centers comprise only about 5 percent of the city. Most Muslims live in contemporary urban environments.”

Since he was appointed to his present position in 2002, Sarkis has been shaping a new program, based at the Graduate School of Design (GSD), that aims to understand the impact of development policies on public space, environmental concerns, land use, and territorial settlement patterns.

The new program complements and expands the Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture, founded in 1979 and based at Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. While the older program focuses chiefly on promoting teaching and scholarship in Islamic architecture, visual culture, and cultural heritage, the new program deals with pressing contemporary issues from a worldwide and comparative perspective.

The topics of recent conferences give some idea of the scope of the program. Last year the program co-sponsored a conference on the reconstruction of cities devastated by disasters such as the civil war that destroyed downtown Beirut. A conference this coming spring will examine the city of Izmir on Turkey’s Mediterranean coast, a pluralistic, cosmopolitan city straddling East and West. Next year, the focus will shift to Africa, and scholars will meet to discuss such issues as relations between northern and sub-Saharan Africa, the concerns of desert environments, and the impact of oil pipelines.

“Each year we will move to a new area and a different set of issues, framed by themes that are of urgent concern around the world,” said Sarkis.

Sarkis has no qualms about expanding the program’s focus to include non-Muslim areas, particularly if those areas share key development concerns or offer instructive regional comparisons. His own GSD course, “Developing Worlds,” looks at planning and design issues in the Middle East and Latin America after World War II, and one of his efforts has been to add case studies from the Muslim world to the core courses that all GSD students take.

“I would like there to be no separation between the study of Muslim architecture and design and the rest of the world,” Sarkis said. “I want to create a program that is so well integrated that it seems invisible.”

In addition to academic activities such as conferences, publications, and new course offerings, the program also works with public authorities and nongovernmental organizations on planning projects and provides opportunities for the staff of these organizations to spend time at GSD. The program also works with the media to promote awareness of the urban and landscape heritage of the Muslim world

In all these activities, Sarkis is guided by a philosophy of development that stresses the interrelationship between economic issues and democratic institutions. It is a philosophy he encountered as a Ph.D. student at the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences studying with Nobel Prize-winning economist Amartya Sen, now Lamont University Professor.

“Amartya Sen had a great impact on my ideas,” Sarkis said. “For him development is always connected with the pursuit of freedom. It’s a symbiotic relationship. I have always asked how this notion affects the idea of design. In the developing world design is often considered a luxury. I want to prove that design is a necessity.”

As a practicing architect, Sarkis has given form to this idea. His design firm, which maintains offices in Cambridge and in Lebanon, where he was born, has undertaken such projects as a housing complex for the fishermen of Tyre, a park in downtown Beirut, two schools in the north Lebanon region, and several urban and landscape projects.

His refusal to dismiss aesthetic concerns, either in his academic activities or in his design practice, continues to be an important principle guiding his development philosophy.

“Many areas in the developing world are rural, and often one of their only strengths is the beauty of the landscape and the purity of the environment. Unless development takes these qualities into account, then even these few assets will be annihilated.”