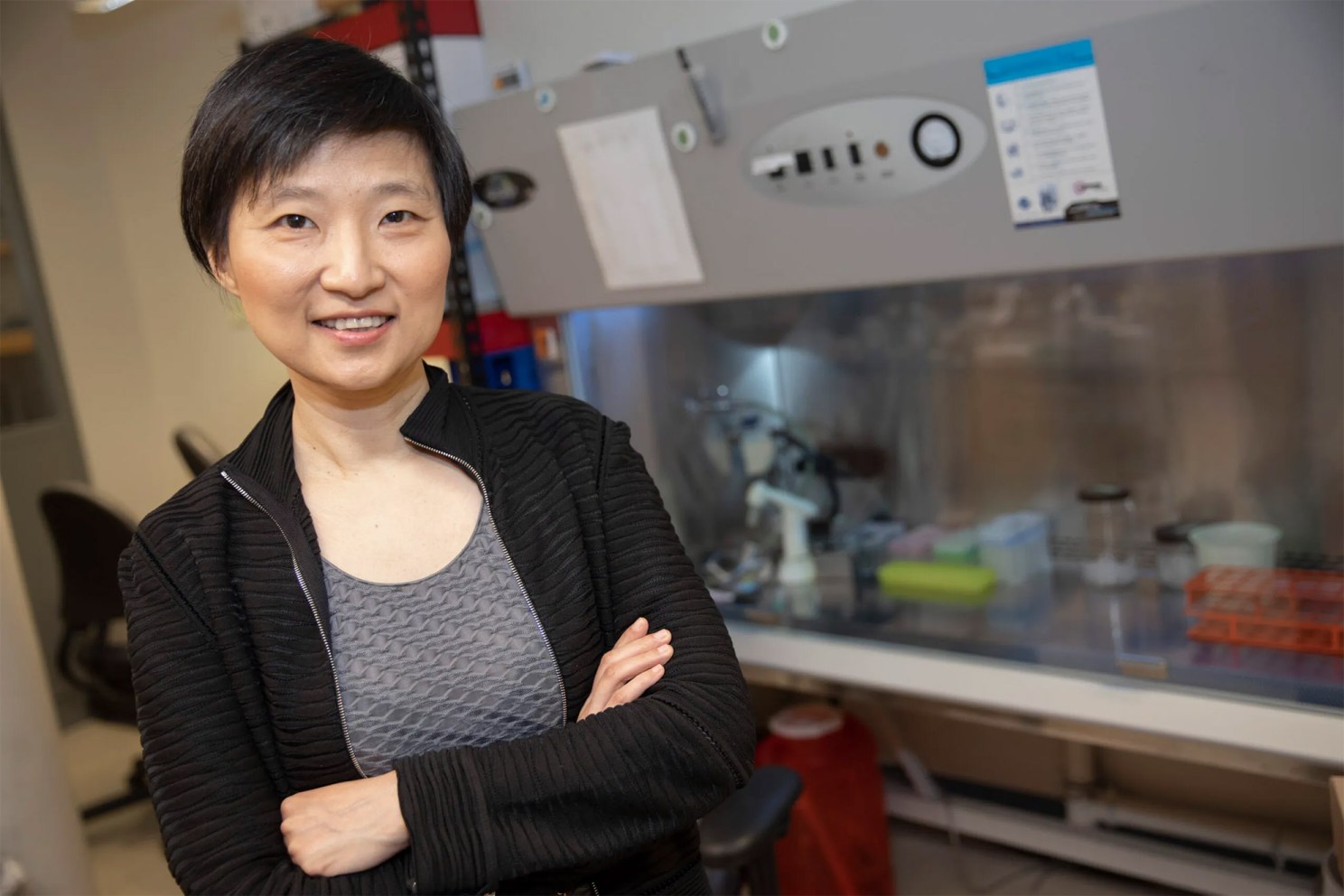

Xiaowei Zhuang awarded the 2026 Ernest Solvay Prize

Xiaowei Zhuang, David B. Arnold Jr. Professor of Science at Harvard University and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator.

Xiaowei Zhuang, David B. Arnold Jr. Professor of Science at Harvard University and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator, has been awarded the 2026 Ernest Solvay Prize by Syensqo “for pioneering the development of genome-scale imaging, which has transformed biochemical research, enabled spatial genomics, and created a new paradigm for understanding the molecular and cellular architecture of complex tissues.” The €300,000 prize will be awarded on March 10 at the Palais des Académies in Brussels.

“I am deeply honored to receive the Ernest Solvay Prize,” Zhuang said. “This recognition highlights the importance of curiosity-driven research and reflects the collective efforts of many talented students, postdocs and collaborators who worked together to make the inner workings of cells and organisms visible and understandable.”

Zhuang is being honored for developing powerful imaging techniques that allow scientists to map and visualize the inner organization of cells and tissues at an unprecedented scale. These methods reveal not only how living organisms function and respond to changes at the molecular and cellular levels, but precisely where that function and response occur.

“It is an honor to award Prof. Xiaowei Zhuang the 2026 Ernest Solvay Prize for her groundbreaking work in advanced molecular and cellular imaging,” said Mike Radossich, CEO of Syensqo.

Zhuang’s career has been driven by the belief that many important questions in biology are inaccessible without new tools. “In general, a lot of problems are still beyond our reach because of major gaps in technology,” she said. “We love developing technologies to allow us to see things that were just plainly not possible before.”

Zhuang’s lab is well known for developing groundbreaking imaging technologies. For example, her lab developed STORM (stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy), which breaks the classical diffraction limit and allows light microscopy with nanometer-scale resolution, and MERFISH (multiplexed error-robust fluorescence in situ hybridization), which enables molecular imaging at the genome scale. The latter won her the Solvay Prize.

In living organisms, thousands of genes together determine a cell’s identity and function, and thus, methods investigating these systems at the genome scale are required for a comprehensive understanding. Yet many genomics methods lose information about where cells sit in a tissue. “Single-cell RNA sequencing is a transformative technology,” Zhuang said, “but it requires dissociation of cells from the functional tissue. As a result, the spatial context of the cells is lost, which is actually very important for tissue function.”

Her response was MERFISH, a genome-scale imaging method that profiles RNA molecules directly inside intact tissues. “Our idea of combinatorial labeling and sequential imaging allows us to scale up to the genome scale,” she said, “and our idea of using barcodes capable of error correction ensures high measurement accuracy. By imprinting error-robust barcodes on RNAs and reading them out bit-by-bit, MERFISH can image thousands to tens of thousands of genes in individual cells.

The power of MERFISH lies its ability to unite molecular identity of cells with their spatial organization. Zhuang and collaborators have used it to build cell atlases of tissues such as the mouse and human brain — revealing how many cell types are present, how they are organized, and how they communicate. In addition, her lab has combined MERFISH with pooled genetic perturbations, assigning each perturbation a barcode that can be read out by imaging, to create high-throughput genotype–phenotype maps. Using this approach, she and collaborators uncovered molecular mechanisms underlying processes such as liver metabolism and stress responses.

For Zhuang, this genome-scale view is essential. “Inside our cells, numerous genes collectively give the cell its function and behavior,” she said. “If we study one gene at a time, we don’t really get the full picture. To have a holistic understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying cellular functions, it requires genome-scale imaging.”

Using MERFISH, her lab and collaborators have mapped how distinct types of cells are spatially organized, interact and connect those patterns to behavior and disease.

Looking ahead, Zhuang offers a vivid metaphor for what this could become. “This approach can eventually give us a Google map of cells in living organisms,” she said. “You can zooming in to see details, or zoom out to see the whole picture, and to interrogate it in an interactive way.”

Throughout, she emphasizes the interplay between new tools and new biology — and the people who make both possible. “I always felt very fortunate to have all these talented and dedicated lab members and love doing creative work together with them day in and day out.”