New tools for preventing the next pandemic

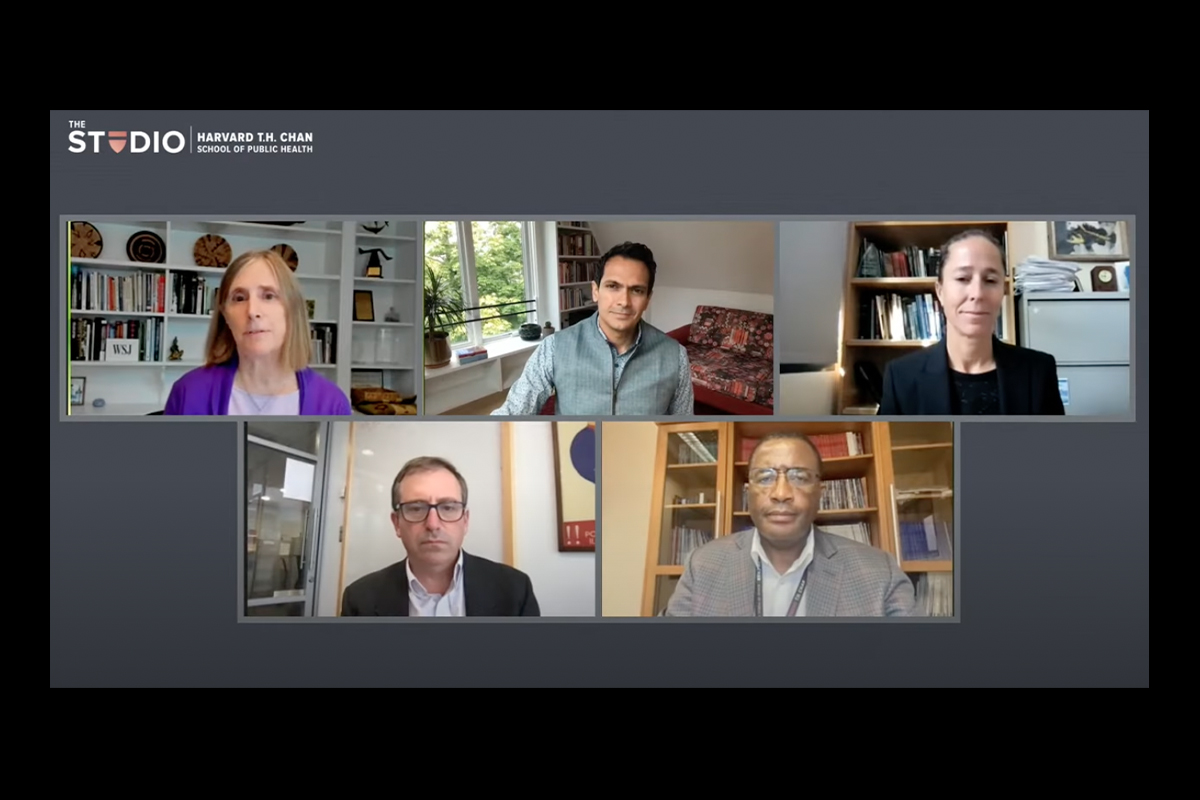

Moderator Betsy McKay (clockwise from top left), Satchit Balsari, Alexandria Boehm, Sikhulile Moyo, and Marc Lipsitch.

In November 2021, researchers in the Botswana lab of Sikhulile Moyo discovered a coronavirus genome that contained dozens of new potentially dangerous mutations. The researchers rapidly alerted the rest of the world about the mutated virus — which eventually became known as the highly transmissible Omicron variant.

With the quick warning, public health officials ramped up vaccination programs and reimplemented social distancing measures. “Governments were able to respond in a matter of days and not months, and that was very important to try and slow the transmission,” said Moyo at an Oct. 17 event at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. He is the laboratory director of the Botswana Harvard AIDS Institute Partnership and a research associate in the Harvard Chan School Department of Immunology and Infectious Diseases.

Technologies such as genomic sequencing have proved to be invaluable in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic and will be important in preventing future infectious disease outbreaks, according to experts who spoke at the event.

Alexandria Boehm, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Stanford University, spoke about her efforts to detect viral genetic material in California wastewater. Because her measurements helped to predict the number of COVID-19 cases, the method has become widely used across the U.S. as an early warning system for potential surges.

“Wastewater represents this amazing resource that seems to work well for surveying all sorts of infectious diseases,” said Boehm. Her team is now applying wastewater detection to emerging outbreaks, including flu and monkeypox.

Satchit Balsari, assistant professor of global health and population at Harvard Chan School, spoke about his work helping to develop a COVID-response tool based on cell phone location data. Researchers gathered anonymized, aggregated location information from cell phone towers and social media apps, using it to analyze how people’s movement affected COVID-19 case numbers. The results successfully helped local, state, and national agencies to adjust policies for specific locations around the country.

In order to make the best use of multiple promising tools that could help prevent future infectious disease outbreaks, it will be crucial to combine different data sources, according to Marc Lipsitch, professor of epidemiology, director of the Center for Communicable Disease Dynamics at Harvard Chan School, and director of science at the recently formed Center for Forecasting and Outbreak Analytics at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“Our new center is designed … to pull in data from multiple sources and produce short-term forecasts, long-term scenario projections, and answers to analytical questions, such as: How should we formulate testing policy? How should we formulate isolation policy? Is there any benefit to closing to closing borders?” Lipsitch said.

In addition to COVID-19, his team is monitoring trends in other outbreaks, including monkeypox. The work depends on early detection systems being in place before a public health threat emerges. “Maintaining the momentum and the interest and not falling into the classic panic-and-then-neglect cycle of public health funding is something we have to be conscious of,” Lipsitch said.