Nearly half of childhood cancers worldwide undiagnosed

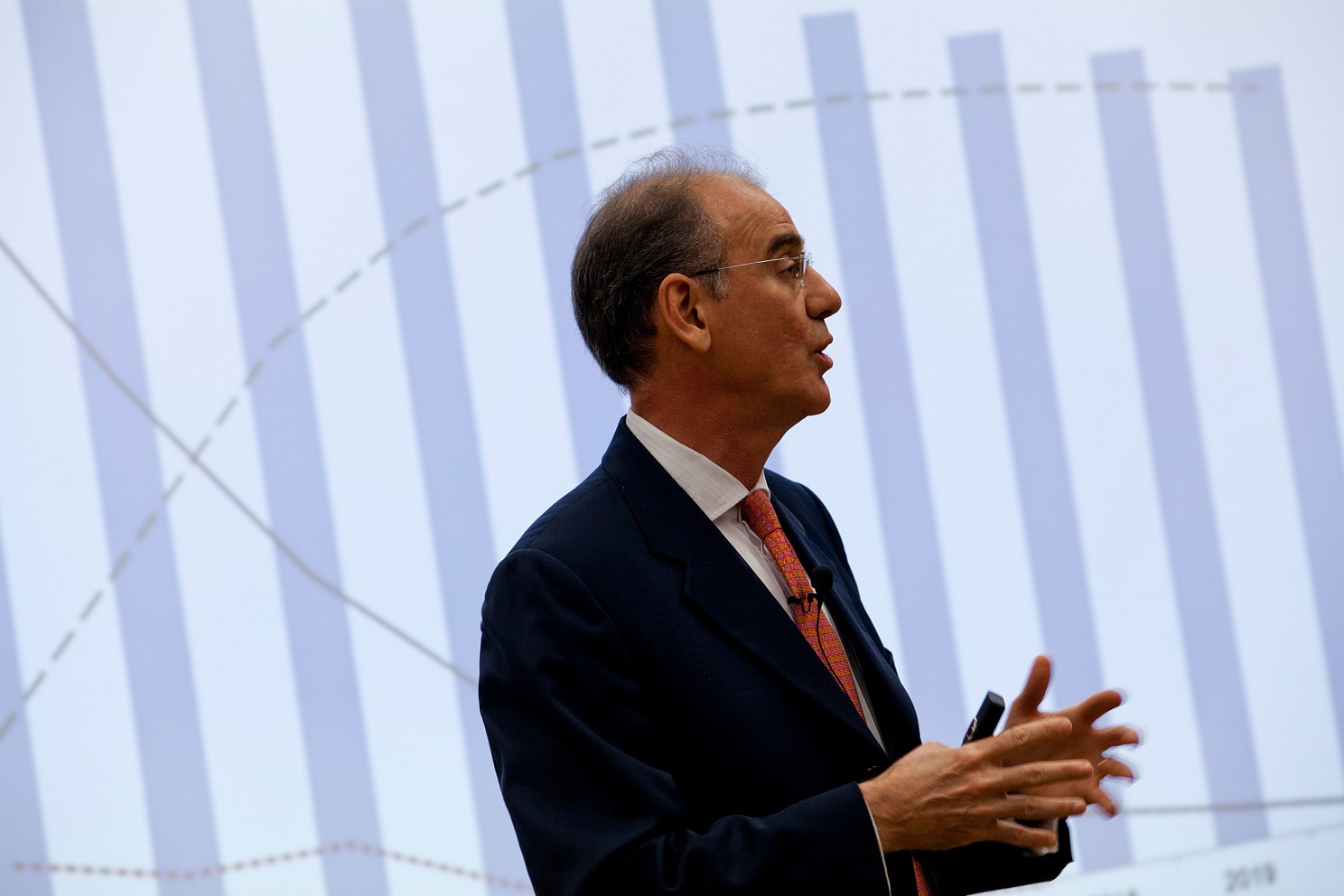

Rifat Atun is the senior author of the study. Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard File Photo

Nearly half of all childhood cancers are not being diagnosed globally, according to a new modeling study led by Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

The study found that, in 2015, there were 397,000 cases of childhood cancer worldwide, but only 224,000 were diagnosed. And if health systems around the world don’t improve, the researchers estimate that 2.9 million out of 6.7 million projected childhood cancer cases — 43 percent — will be missed between 2015 and 2030.

The study was published Feb. 26, 2019 in Lancet Oncology.

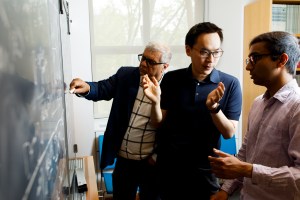

“Our model suggests that nearly one in two children with cancer are never diagnosed and may die untreated,” said lead author Zachary Ward, a doctoral student in health policy at Harvard Chan School. “This new model provides specific estimates of childhood cancer that have been lacking.”

Accurate estimates of childhood cancer incidence are needed to inform health policies, but many countries don’t have cancer registries that quantify this incidence. In addition, existing registries may underestimate the true incidence of childhood cancer, according to the authors.

In the new study, researchers developed a model to simulate childhood cancer incidence for 200 countries and territories worldwide. The model included data from cancer registries in countries where they exist. It also took into account trends in population growth and urbanization, geographical variation in cancer incidence, and health system barriers to access and referral that contribute to underdiagnosis.

The prevalence of undiagnosed cancer cases varied widely across regions, from just 3 percent in western Europe and North America to 57 percent in western Africa, the study estimated. In south Asia, 49 percent of cases were undiagnosed. The researchers said that 92 percent of new cases of cancer are occurring in low- and middle-income countries, a higher proportion than previously thought.

The authors hope that their findings will help guide health systems in setting new policies to improve diagnosis and management of childhood cancers.

“Health systems in low-income and middle-income countries are clearly failing to meet the needs of children with cancer,” said Rifat Atun, professor of global health systems and senior author of the study. “Universal health coverage, a target of United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, must include cancer in children as a priority to prevent needless deaths.”

Funding for the study came from Boston Children’s Hospital, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Chan School, Harvard Medical School, the National Cancer Institute, SickKids, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, and the Union for International Cancer Control.

[gz_explore id=”265502,229321″ alignment=”center” /]