Maine policy restricts tribal sovereignty finds new research

In case after case, self-determined, self-governed tribal economic development spills over positively into neighboring non-tribal communities and improves governance generally.

A team of Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development researchers at Harvard Kennedy School today released a research report documenting the costs to the Wabanaki Nations in Maine—Maliseet, Mi’kmaq, Passamaquoddy, and Penobscot—and to Maine’s non-tribal citizens of the state’s being screened off from federal policies of Indian self-determination and self-governance.

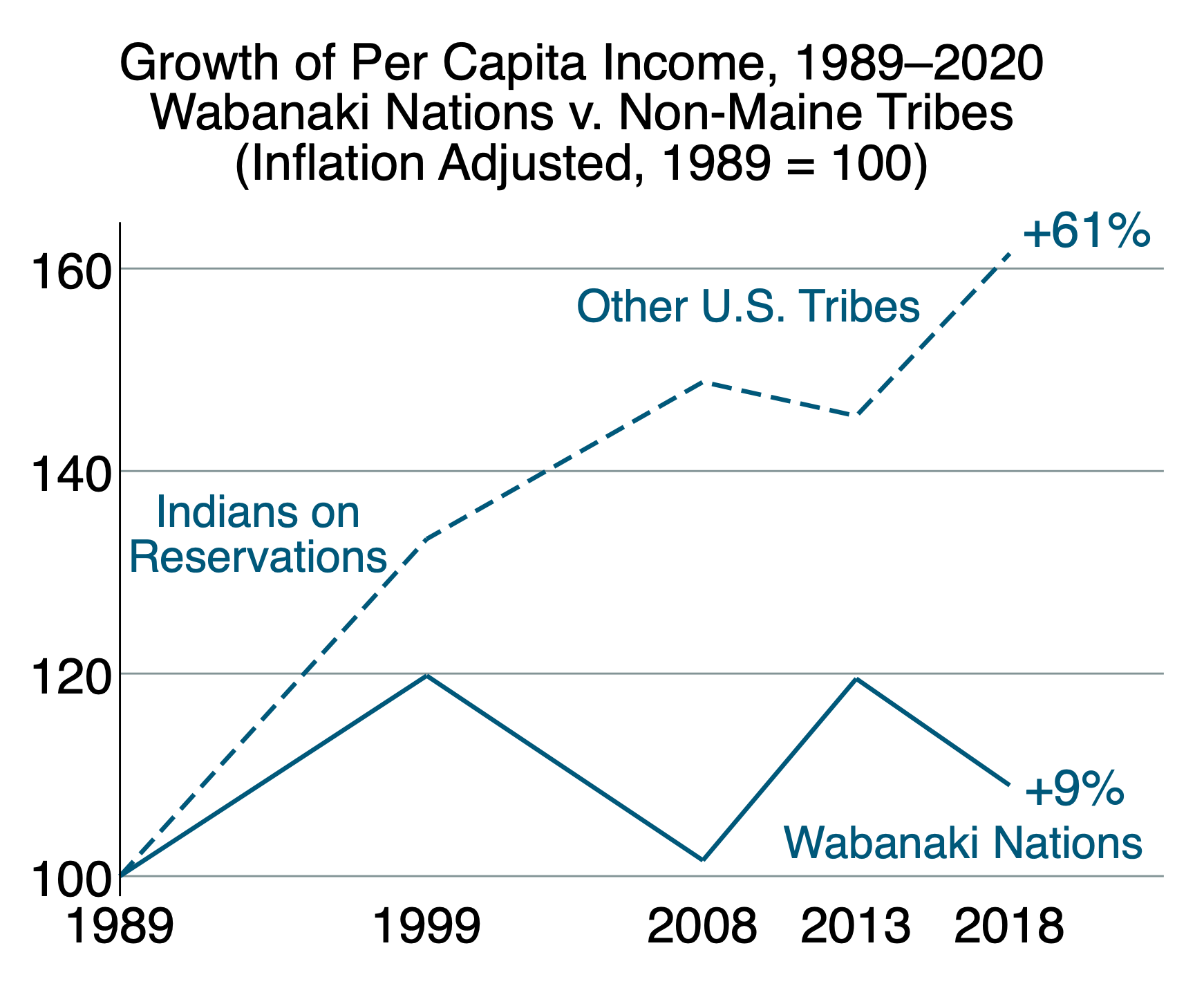

For the last several decades, self-governance policies have produced remarkable economic growth across most of Indian Country and expanded the responsibilities and capacities of tribal governments. Hundreds of tribes across the other Lower 48 states now routinely provide their citizens with the broad array of services normally expected from state and local governments, and an increasing number of tribes are becoming the economic engines of their regions.

For the last several decades, self-governance policies have produced remarkable economic growth across most of Indian Country and expanded the responsibilities and capacities of tribal governments. Hundreds of tribes across the other Lower 48 states now routinely provide their citizens with the broad array of services normally expected from state and local governments, and an increasing number of tribes are becoming the economic engines of their regions.

The federal Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act of 1980 (MICSA) empowers the state government to block the applicability of federal Indian policy in Maine. As a result, all four Wabanaki Nations are stark economic underperformers relative to the other tribes in the Lower 48 states.

For the tribal citizens of Maine held down by MICSA’s restrictions, loosening or removing those restrictions offers them little in the way of downside risks but much in the way of upside payoffs. Notably, “nowhere to go but up” also applies to the Maine state government and Maine’s non-tribal citizens. Under federal policies of tribal self-determination, tribal economic development spills over positively into neighboring non-tribal communities and improves the abilities of tribes and state and local governments to serve their citizens.

As with any neighboring governments, conflicts can arise between tribal and non-tribal governments. The overall experience outside of Maine has been that increasingly capable tribal governments improve state-tribal relations by enabling both parties to cooperate productively. Against these positive potentials for Maine is a status quo in which all sides leave economic opportunities on the table, and old cycles of conflict, litigation, recrimination, and mistrust continue.