It’s harder for students to think straight during a heat wave, study finds

During a heat wave, students performed worse on smartphone tests if they did not have access to air conditioning. Credit: Brandon Morgan/StockSnap

Students who lived in dormitories without air conditioning during a heat wave performed worse on a series of cognitive tests compared with students who lived in air-conditioned dorms, according to new research led by Harvard T.H Chan School of Public Health. The field study, the first to demonstrate the detrimental cognitive effects of indoor temperatures during a heat wave in a group of young healthy individuals, highlights the need for sustainable design solutions in mitigating the health impacts of extreme heat.

“Most of the research on the health effects of heat has been done in vulnerable populations, such as the elderly, creating the perception that the general population is not at risk from heat waves,” said Jose Guillermo Cedeño-Laurent, research fellow at Harvard Chan School and lead author of the study. “To address this blind spot, we studied healthy students living in dorms as a natural intervention during a heat wave in Boston. Knowing what the risks are across different populations is critical considering that in many cities, such as Boston, the number of heat waves is projected to increase due to climate change.”

The study was published online July 10, 2018 in PLOS Medicine as part of a special issue dedicated to climate change and health.

Extreme heat can have severe consequences for public health and is the leading cause of death of all meteorological phenomena in the U.S. Temperatures around the world are rising, with 2016 marking the warmest year on record for the past two centuries. Understanding the effects of indoor temperatures is important given that adults in the U.S. spend 90 percent of their time indoors.

For this new study, researchers tracked 44 students in their late teens and early 20s living in dorm rooms. Twenty-four of the students lived in adjacent six-story buildings that were built in the early 1990s and had central air conditioning. The remaining 20 students lived in low-rise buildings constructed between 1930 and 1950 that did not have air conditioning.

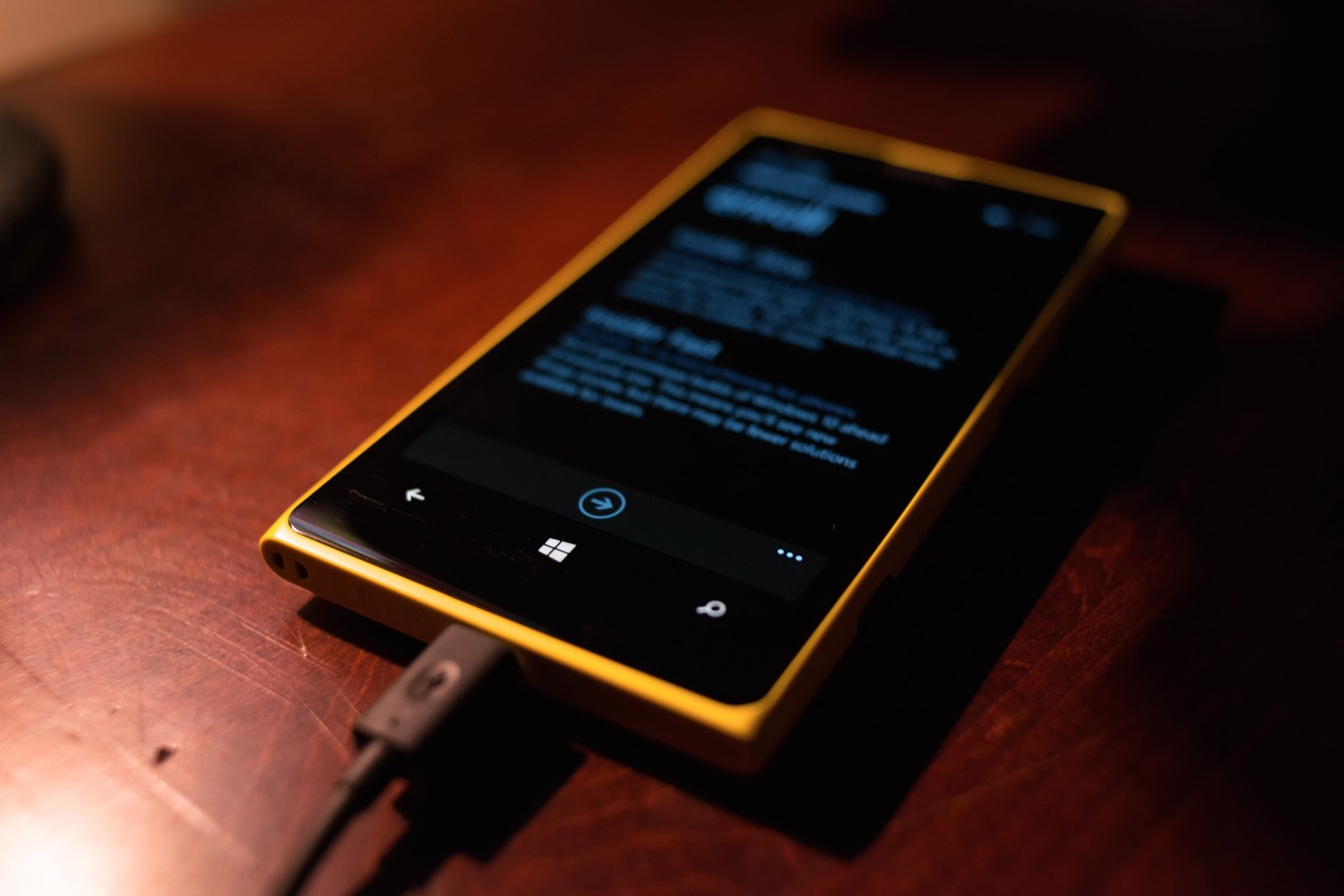

The study was conducted over 12 consecutive days in the summer of 2016. The first five days consisted of seasonable temperatures, followed by a five-day-long heat wave, and then a two-day cooldown. Each day the students took two cognition tests on their smartphones right after waking up. The first test required students to correctly identify the color of displayed words and was used to evaluate cognitive speed and inhibitory control — or the ability to focus on relevant stimuli when irrelevant stimuli are also present. The second test consisted of basic arithmetic questions and was used to assess cognitive speed and working memory.

The c than students in the air-conditioned dormitories and experienced decreases across five measures of cognitive function, including reaction times and working memory. During the heat wave, students in buildings without air conditioning experienced 13.4 percent longer reaction times on color-word tests, and 13.3 percent lower addition/subtraction test scores compared with students with air-conditioned rooms.