In a city defined by water, architects aim to turn threat to opportunity

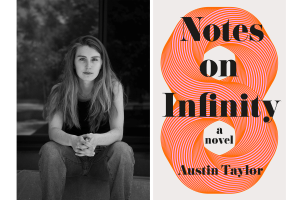

Miami-based architect and urban designer Juan Mullerat interrogates a Harvard GSD proposal for the Miami waterfront. Photo courtesy of GSD

Among American cities, Miami emerges as a particular case study in how and where we will house people as climate pressures mount. Its famous beaches and waterfront condominiums will struggle with sea level rise in the next 50 years — and inland regions will feel pressure, too, as coastal residents search for dry ground. Already, salt water routinely floods Miami’s streets and bubbles up in family yards, permeating the porous limestone bedrock deep underground. While basements and garages flood, developers proceed headfirst into seaside condo projects.

As temperatures, oceans, and anxieties rise, might designers help anticipate — and adapt to — what is now considered the inevitable? In Miami and Miami Beach, what will happen to neighborhoods, like Cortada’s, expected to be underwater within their residents’ lifetimes? Can new buildings, and new strategies, emerge from competing dialogues?

Stoked by this dilemma, Harvard Graduate School of Design professors Eric Höweler, an architect, and Corey Zehngebot, an urban designer and architect, organized a GSD investigation into issues of housing, resilience, and adaptability, using Miami as an urban laboratory. Their investigation, the Fall 2019 option studio “Adapting Miami: Housing on the Transect,” engaged a cohort of 12 GSD students in months of research, site visits, and critical review.

Students generated housing-focused proposals that offer a portrait of Miami’s risks and opportunities. They collaborated with and drew research insights from a concurrent seminar led by Jesse M. Keenan, recognized as a leading researcher on questions of climate and real estate; he has worked to shape a global discourse on the relationship between climate change, social equity, and applied economics.

The geographical and conceptual heart of their study is a periscopic transect of the city created by two of Miami’s most iconic streets — Flagler Street to the north, and 8th Street, also known as Calle Ocho and the Tamiami Trail, to the south — which bracket a swath of Miami’s fabric, cutting westward from the City of Miami’s high-density eastern coastline, through Little Havana, West Miami, and Tamiami, and into the Florida Everglades. This transect captures a range of natural ecosystems and urban conditions while representing the constraints of Miami’s built and natural environments: hard boundaries of high-density urban development at some edges (east, north, and south) and water everywhere else — the Everglades to the west, the Atlantic to the east.

It is along and between these corridors where interesting opportunities for different housing typologies emerge, opportunities that are intertwined with mobility, streetscape design, density, infrastructure, ecology, resiliency, and adaptation, Zehngebot observes.

Read more about Harvard GSD’s investigation, and the building proposals that resulted, at GSD News.