The year was 1988. People were afraid. A total a 106,994 people had been diagnosed with HIV/AIDS in the U.S. and 62,101 were dead. Scientists were making progress, but there was no effective treatment. One night the evening news would feature protests by AIDS activists demanding faster drug approval. The next night the news featured parents demanding kids with HIV be barred from public schools.

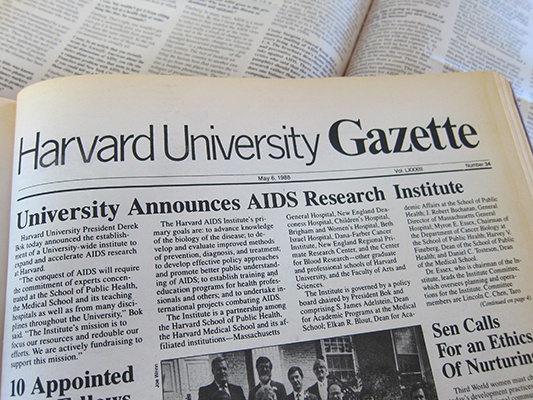

On May 6, 1988, Harvard President Derek Bok announced the establishment of the Harvard AIDS Institute (HAI) to expand and accelerate AIDS research at Harvard. “The conquest of AIDS will require the commitment of experts concentrated at the School of Public Health, the Medical School and its teaching hospitals as well as from many disciplines throughout the University,” said Bok. “The Institute’s mission is to focus our resources and redouble our efforts.”

Bok named Myron “Max” Essex, a virologist at the Harvard School of Public Health (HSPH), to lead the Institute. According to Essex, “HAI was the brainchild of Harvey Fineberg,” who was HSPH Dean at the time.

“I wanted Harvard to declare a clear and compelling commitment to cope with the AIDS epidemic,” remembered Fineberg. “To deal with it not just as an intellectual problem, but as a practical and social problem. Max Essex was the obvious choice to lead the enterprise. He had been at the center of research on retroviruses and what later became HIV/AIDS research.”

After arriving at Harvard in 1972, Essex quickly made his mark. He showed that feline leukemia was caused by a type of infectious disease — a retrovirus — which could also suppress the animal’s immune system. In the early 1980s, when the Centers for Disease Control in Atlanta began investigating deaths in gay men with immunosuppression, Jim Curran, who led the investigation, called Essex for help and sent samples to his lab. Scientists were searching for the cause of what would later be named AIDS.

Essex was one of the first researchers to hypothesize that a retrovirus was the cause of AIDS. Later, he and a graduate student, Tun-Hou Lee, identified gp120, the envelope protein of the virus which became the basis for HIV tests. Essex, graduate student Phyllis Kanki, and their colleagues discovered SIV, an AIDS-like virus in monkeys. They also identified HIV-2 in West Africa, a virus similar to but less lethal than the more common HIV-1.

“It was a time when discoveries were happening almost monthly — major discoveries,” remember Richard Marlink, a young doctor who joined the Essex team. “Tun-Hou Lee and Phyllis Kanki and others were figuring out where the virus came from and how it worked.”

As AIDS took hold in the 1980s, Essex and his team collaborated with other scientists and clinicians in the Boston area, including Martin Hirsch, head of infectious diseases at Massachusetts General Hospital; William Haseltine, a molecular biologist at the Dana Farber Cancer Institute; and Jerome Groopman, an oncologist studying AIDS-associated cancers at the Deaconess Hospital.