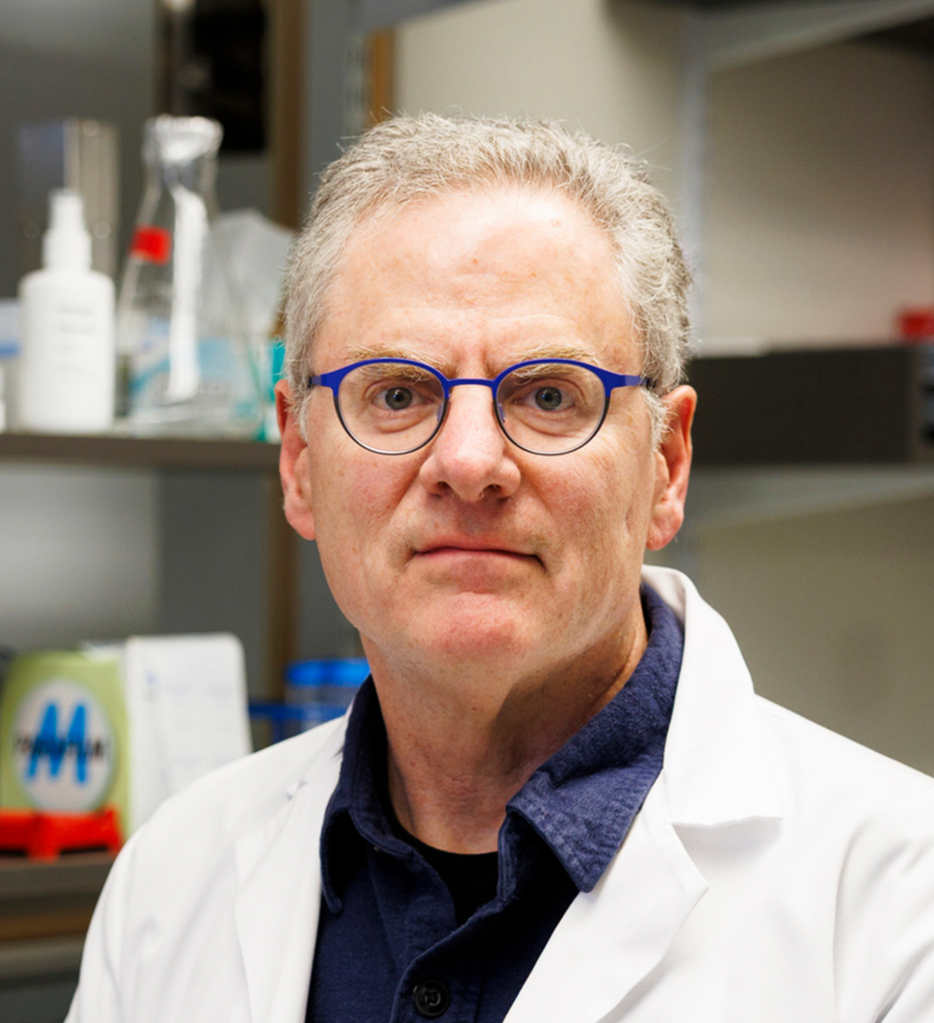

Eric Pierce using a NovaSeq 6000 machine in the lab.

Niles Singer/Harvard Staff Photographer

Turns out inherited eye diseases aren’t a sure thing

Study finds only fraction of those with mutated gene develop malady — a finding that could lead to better treatments (and could apply to other such illnesses)

Inherited eye diseases long believed to be inevitable for those with a certain mutated gene actually occur in just a minority of those cases, according to a recent study. Researchers made the discovery after turning their focus from individual patients to the whole population.

“What I’m excited about here is this creates an amazing opportunity to understand disease causality but also identify novel targets for treatment.”

Eric Pierce

“What I’m excited about here is this creates an amazing opportunity to understand disease causality but also identify novel targets for treatment,” said Eric Pierce, the William F. Chatlos Professor of Ophthalmology at Harvard Medical School and the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, one of the study’s senior authors. “If we can figure out why people don’t get disease when they’ve got these variants, that would be incredibly powerful for therapies to prevent vision loss from these disorders.”

The findings by Pierce, co-senior author Elizabeth Rossin, and colleagues from the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary’s Ocular Genomics Institute and Harvard Medical School, astonished researchers, who said the results indicate much larger influence than expected of “ascertainment bias” — caused by physicians normally seeing only those with the highest chances of developing disease.

They also say it is possible that these findings could have implications for other inherited diseases such as Huntington’s disease, muscular dystrophy, and others.

The discovery was made possible by the development in recent years of “biobanks” that pair the biological samples of massive numbers of individuals with their electronic medical records. That pairing allows investigators to examine an array of conditions from the standpoint of the broader population rather than depending on individual cases.

Eric Pierce.

Niles Singer/Harvard Staff Photographer

Elizabeth J. Rossin.

Photo courtesy of Elizabeth J. Rossin

The physicians were studying a family of inherited retinal diseases, which include some of the most common causes of blindness, such as inherited retinitis pigmentosa, inherited macular degeneration, and Leber congenital amaurosis.

The diseases are “monogenic,” which means they are believed to be caused by mutations in a single gene. Further, some are dominant, which means the mutation has to be present in only one of the two copies of each gene that humans naturally carry in order to cause disease.

For decades, physicians believed that those with the mutation universally developed problems with their retinas — the light-sensitive layer at the back of the eye — leading to visual impairment and blindness.

But Pierce said clinicians who saw patients with these diseases also occasionally saw cases where patients’ parents or grandparents reported no vision problems.

“I think all of us who study the genetics of rare disease have known for a while that the single pathogenic variants we identify as causing disease aren’t the whole story.”

Eric Pierce

That was a hint that the understanding of those conditions was incomplete, because, in dominant disorders, at least one parent had to have a copy of the mutated gene to pass it along. And if that were the case, they would also have the disorder.

“I think all of us who study the genetics of rare disease have known for a while that the single pathogenic variants we identify as causing disease aren’t the whole story,” Pierce said. “With a dominant disease, you should see a person affected in every generation, but we see generations that are skipped.”

That contradiction led Pierce, Rossin — who is an HMS assistant professor of ophthalmology — and their team to suspect “ascertainment bias” at work in our understanding of these conditions: Physicians would routinely care for patients with these diseases, and whenever genetic testing was done, analysis would reveal a mutated gene.

Missing from physicians’ experience, however, were those in the population who had the mutation but didn’t develop the condition, and so never sought medical care.

Pierce and colleagues decided to take advantage of the development of large, population-wide databases containing genetic information, biological samples, and participants’ medical records. What the broader view from those biobanks showed, Pierce said, was “striking.”

Using the U.S.-based “All of Us” biobank, researchers examined the genetic background and medical history of more than 300,000 Americans.

They studied 167 genetic variants that were implicated in some 33 different genetic forms of inherited retinal diseases. Then, by cross-checking medical records, they found that those with a mutated gene developed retinal disease far more infrequently than expected.

Instead of a figure close to 100 percent, only between 10 percent and 30 percent of participants developed retinal disease. That flips the medical dogma on its head, showing that the vast majority — between 70 percent and 90 percent — of those with the mutation don’t develop disease.

They then checked those findings in the UK Biobank, which includes about 100,000 people with retinal imaging, and the results were similar.

“What we found was striking,” Pierce said. “Seventy to 90 percent of people with variants that have been reported to cause disease — in fairly robust genetic studies of affected individuals — are not diagnosed as having disease in their electronic health records. It’s a much larger effect than I expected.”

“I think what’s happening biologically is you have to have these variants to get disease, but in order for the disease to actually develop, the rest of your genetic makeup needs to be taken into account.”

Eric Pierce

The implication, Pierce said, is that there are other factors — likely genetic but potentially also environmental — that play important roles in determining whether someone with a genetic mutation develops the condition.

“We have historically focused on people who have not just the variants which are needed to cause disease, but who also have a genetic background that allows that disease to be expressed,” Pierce said. “I think what’s happening biologically is you have to have these variants to get disease, but in order for the disease to actually develop, the rest of your genetic makeup needs to be taken into account.”

The findings, published in December in the American Journal of Human Genetics and funded by the National Eye Institute and several private foundations, has implications beyond the genetic eye diseases in this study, Pierce said.

A host of other diseases can also be traced back to mutations in single genes. Among them are Huntington’s disease, polycystic kidney disease, muscular dystrophy, and inherited heart disease. For all of those conditions, a better understanding of what might inhibit a genetic disease might lead to new interventions, Pierce said.

“For all of these rare, inherited disorders with unmet medical needs for which there aren’t effective therapies or not as many effective therapies as we’d like, my prediction is that the same kind of phenomenon will be identified,” Pierce said.