‘Harvard Thinking’: Preserving learning in the age of AI shortcuts

Illustrations by Liz Zonarich/Harvard Staff

In podcast, teachers talk about how they’re using technology to supercharge critical thinking rather than replace it

Concerns of artificial intelligence supplanting human thinking are rising amid the exponential growth in recent years of generative AI’s capabilities. One thing is clear: The technology is not going away.

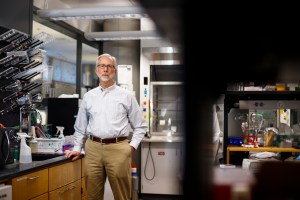

“I feel it would be irresponsible for me not to embrace it entirely, both in the classroom and in research,” said Michael Brenner, the Catalyst professor of Applied Mathematics in the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences. In his view, anyone who doesn’t is going to lag in their careers and their ability to advance science. “It’s just changed everything.”

Reports of AI harming the social, emotional, and cognitive development of students need to be taken seriously, said Tina Grotzer, a cognitive scientist at the Graduate School of Education. The challenge for educators is determining how to incorporate the technology in the classroom so that it enhances learning rather than replaces it.

Ying Xu, an assistant professor at the Graduate School of Education, meanwhile, encourages parents who are worried about how to introduce AI to their kids to consider it in relationship to “the larger ecosystem of a child’s life,” including building healthy relationships, spending time outdoors, and pursuing hobbies.

In this episode of “Harvard Thinking,” host Samantha Laine Perfas talks with Brenner, Grotzer, and Xu about how educators and parents can harness AI’s educational benefits while mitigating potential risks.

Listen on: Spotify Apple YouTube

The transcript

Tina Grotzer: Once you start to know what your mind can do that’s so much better than AI, it kind of makes sense that some tasks are well-relegated to AI and other tasks are not. That is going to be a constant challenge to figure out those relationships and lines over time.

Samantha Laine Perfas: As generative AI tools become more ubiquitous, there’s a debate around whether or not they should be embraced in spaces of learning. Recent reports suggest that the risks of using these tools might outweigh the benefits, threatening cognitive development by doing the thinking for their users. Homework that used to take hours of practice and comprehension is now completed in minutes, potentially undercutting students’ development of basic skills. This is forcing educators into a dilemma: How do they make the most of AI’s potential, while also protecting students’ ability to think for themselves?

Welcome to “Harvard Thinking,” a podcast where the life of the mind meets everyday life. Today we’re joined by:

Michael Brenner: I’m Michael Brenner. I’m the Catalyst Professor of Applied Mathematics in the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences at Harvard.

Laine Perfas: He is also a research scientist at Google, where he runs a team that studies how large language models can accelerate science. Then:

Grotzer: Tina Grotzer. I am on the faculty at the Graduate School of Education.

Laine Perfas: She’s a cognitive scientist and studies how people learn. And our final guest:

Ying Xu: Ying Xu. I’m an assistant professor of education at Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Laine Perfas: She researches how to best design and evaluate AI technologies so they enhance children’s development rather than harm it.

And I’m Samantha Laine Perfas, your host and a writer for The Harvard Gazette. Today we’ll talk about the role of AI in our educational settings and how we might best use it to enhance our learning rather than replace it.

There are concerns that generative AI tools will increasingly affect our ability to learn. So I want to talk about the act of learning itself and critical thinking. What is it that we’re afraid will be affected?

Grotzer: We’ve been a knowledge economy, so a lot of what we do in schools is about learning facts, memorizing things, getting a lot of information that we can then hopefully transfer forward and use in the real world. But learning also involves thinking about your mind, how we use our minds well, understanding our minds, understanding what critical thinking is, whatcreative thinking is. And so much of it we do so naturally that I think kids don’t even realize that they need to learn to do it. They don’t reflect on the amazing learning that their minds are doing day after day. That’s really important for this conversation.

Xu: We are thinking about learning along two dimensions. One is what they learn, like the facts and the information. And the other one is their ability to learn. And those are really the foundational capacities that allow students to acquire new knowledge and skills in the future, and critical thinking is one of these very important foundational capacities.

Brenner: I’m very interested in what Ying and Tina just said. I see the problem from maybe the other side, which is that my teaching focuses on advanced undergraduates and graduate students who are basically trying to learn to make models to understand or improve the world. For example, making large language models, the foundation of generative AI. And my career has really been driven by making scientific advances and trying to make discoveries using all of the tools in actual practice. And I should say upfront before I say the next thing that I am quite concerned about generative AI and its use and what it’s going to do to the people learning basic skills. Having said that, I feel it would be irresponsible for me not to embrace it entirely, both in the classroom and in research. And the reason is that anyone who doesn’t embrace it is going to lose. They’re going to get behind in terms of their careers, they’re going to get behind in terms of not making the greatest advances; it’s just changed everything. I’m excited that Tina and Ying are here because I’ve always worried that I don’t know how to teach people how to do the chain rule, which is the first thing you have to learn when you do calculus. But once you know that, then you need to proceed as I’m describing. But I have no idea what we’re supposed to do about actual learning.

Laine Perfas: I think that brings up an important point. Learning is obviously a lifelong endeavor, so when we talk about AI tools, I imagine there is a huge difference between incorporating it into an elementary or middle school or high school classroom. Does it matter the age at which these tools are being introduced and incorporated into learning?

Grotzer: I work with a lot of teachers who are thinking about instructional design, and what I often see in their work is that for the youngest children, they think that the kids need to learn a lot of information, and then once they have a lot of information they can learn how to think with it. And I think that’s unfortunate because you see the very youngest kids experimenting, exploring, demonstrating curiosity. This is all to Michael’s point, really, that AI is in the world, and why would we stop them from learning about the things that are out there? I do think that the very youngest children don’t have a reflective sense of what it is. But they’re going to interact with it, so I think figuring out how it can be a part of their world and a part of their exploration and their play without creating assumptions around — you know, it’s not really your friend, the anthropomorphizing of AI, things like that — are important. When we start to look at placing developmental limits, that becomes problematic when we’re talking about learning in the real world every day.

Xu: When I talk to parents, the question that gets asked the most is at what age should we introduce AI toys at my home and at what age it starts to be safe for my kids to interact with AI tools. And what I would say is, “What kinds of tools are we thinking of introducing?” There are some tools that are more specialized, like the ones designed specifically to teach phonics and to support math and science. And there are also some tools that are designed with kids in mind that support this safe exploration, like Tina just mentioned. But there is another category that is more of this general tool that could be an assistant for almost everything. I do feel that to be able to use this kind of general tool, it does require some cognitive skills that our students need time to develop. For example, what we found was self-regulation is one of the very important skills that students need to be able to interact with AI tools effectively because they need to actually make a plan. And this is the kind of learning that I wanted to engage: I am going to do the thinking myself but only use AI for some scaffolding. And this needs some regulation to control the temptation: “I’m not going to ask AI for answers for all the questions.”

We did a survey with 7,000 high school students. We asked them, “Do you feel that you are relying on AI too much for your learning?” And almost half of those students said that, “Yes, I feel that I’m using AI a bit too much.” And then over 40 percent said, “I tried to limit my usage, but it was so difficult I failed.”

Laine Perfas: It’s interesting that there is the self-identification of I don’t want to be using it as much, and also, I can’t help myself, which I think may be why technology in general can be such a tricky thing for young people. It seems that there’s this tension: AI is in the world. It’s going to be around us. How do we bring it in in a way that enhances learning versus replaces learning?

Brenner: I think that because we have AI, students should do more, they should solve harder problems. They should learn more. That’s my answer. And I’ve done this in various ways through classes at Harvard. One example is from a class that I teach, which is a graduate class in applied mathematics, which has always been thought of as one of the harder classes that we have.

“I think that because we have AI, students should do more, they should solve harder problems. They should learn more.”

I taught it last spring, and the day before I went to lecture, just for fun, I stuck in my last homework problem set into Gemini and asked it if it could solve it. And it basically solved everything. I was quite shocked because these are things that people spend their lives learning how to do. But I decided that I would walk in and just say to the students, “Well, this now happened. And so my syllabus is now invalid.” Basically, I’m not going to read problem sets given by ChatGPT. And so instead what I did is I completely changed the class and made two different things, which I think raised the level significantly. One is that every week, instead of giving them a problem set where I gave problems and asked them to solve it — which is the way I’d always done it — I instead told them that they needed to invent a problem that was in a particular category, and that the problem had to have the characteristic that the following chatbots could not solve the problem. And if they found the problem that the best chatbot couldn’t solve, they got extra credit. Meanwhile, they had to verify that their solution was correct by doing certain numerical calculations, and they had to convince someone else in the class that it was correct. We did that every week. There were 60 students in the class. By the end of the semester, we had 600 problems that, for the most part, the best chatbots at the moment couldn’t solve. We as a class wrote a paper about this and it was just published with everybody in the class as authors.

But then that was not enough, because of course, teaching students, you still have to know that they understand. So what I did — and I’ve now started doing — is in lieu of a final exam, I basically carried out oral exams with each of the students in which they had to walk in, and I said, “You’ve invented these 10 problems,” and I made them go to my blackboard, and I picked one — I didn’t let them choose — and I made them go and solve it, basically, then explain to me how they came up with it. I learned more about the students than I ever have in the past in such a class. Subjectively, they knew more than anyone that I’d ever taught before because they were forced to go and read things that they ordinarily wouldn’t need to read because they had to push the state of the art.

Grotzer: I have an assignment that I give to my students that I’ve given them for the last 20 years, and it has a number of points in this semester where they turn it in and they get feedback. And this was the first year where I could clearly see significant use of AI in the assignment. And what was supposed to be a 20- or 30-page assignment — I’m reading 60 pages of glop, it’s not terribly thoughtful.

We had a long talk about, if you are designing instruction for the next generation, do you want to design the very best instruction that you can? You’re paying to come to school to learn how to do these things. Do you want to leave without pushing at the edges of your own learning and your own competence? So let’s talk about the ways that you’re using this. Some of the ways that students used it made a lot of sense. They had it quiz them about things they were trying to do. They asked for feedback on certain aspects, they explored possibilities and then went through and selected the ones that were most powerful for their own instructional designs. They also — very interestingly, some of them used it to create different perspectives on something that they were creating. So if you were a parent reading about this assignment, what would you wonder about? If you were a kid reading this assignment, what problems would be confusing to you? I think it’s really encouraging them to continue to work at the edge of their competence. Use it as a tool to transform what they’re doing. Which is really what I was hearing from Michael when he’s thinking about these assignments that he’s getting that are just much more advanced than you otherwise would’ve gotten.

One of the issues is that we have a crisis of purpose in education, and we need to be rethinking what it is that young people learn as they progress through our educational system. Ying talked about the importance of self-regulation, so that’s important all the way through. We can all get behind that, but they’re always going to be in a world where there are going to be new innovations, and the innovations are going to get better and better in some respects. I think it forces us to look at what it is that we’re teaching and why.

Xu: I wanted to linger on the purpose of education. In the same survey that we asked the 7,000 high school students, “What is the purpose of your learning?”, we asked whether they feel that learning math and learning English is still as important as before AI was introduced. Not surprisingly, we saw a huge decrease of students’ motivation in those two important subjects. This is a wake-up call and a moment for educators to think about how we could restructure education and restructure the classroom and learning so that it’s more relatable for what students want to do in their life.

“This is a wake-up call and a moment for educators to think about how we could restructure education so that it’s more relatable for what students want to do in their life.”

Laine Perfas: Thinking about the purpose of education and classrooms and how they are needing to evolve to account for this technology, which is a tale as old as time. We had to evolve when calculators were invented, when computers were invented. But just thinking about that and thinking about the traditional assignment as we have known them or as I knew them growing up, so many of them were transactional in nature. An example might be writing an email. It’s not about, “I want to have a really good grasp of language so I’m a good communicator.” It’s, “I want to get this email written as quick as possible.” I’m wondering how you see things needing to switch so that students remember that the point is learning, versus getting work done as efficiently as possible.

Grotzer: I’d like to put a plug in for metacognition, which is understanding and thinking about your own mind and your own thinking, as one of the shifts that we need to make in terms of the purposes of education. We talk a lot about getting to know how human-embodied minds are powerful. And we contrast that with what AI can presently do. Once you start to know what your mind can do that’s so much better than AI, it makes sense that some tasks are well-relegated to AI and other tasks are not. That is going to be a constant challenge to figure out those relationships and lines over time, especially given how much AI is advancing and that it’s really a moving target.

“Once you start to know what your mind can do that’s so much better than AI, it makes sense that some tasks are well-relegated to AI and other tasks are not.”

In my “Becoming an Expert Learner” class, we look at aspects of human-embodied minds. And in every class, I ask them to start thinking about, Can AI do these things? How does AI contrast to the human mind in this sense? And then they make a great big Venn diagram and really think about it. Our minds are very different from what AI is doing.

But that’s my plug for metacognition. I think we need to be metacognitive both about our minds and about AI, and that’s a new purpose for education.

Brenner: Just to respond to that briefly, I agree that we should be metacognitive about what we’re learning and why we’re learning it, and we should think about it and we should teach our students how to do that. I agree that’s important. On the other hand, the one thing where I would push back slightly — and again, this only applies to my world, which is teaching people towards the end of their formal education — is that, I used to think I was a kind of creative person, basically. I’ve written a lot of papers in my life and I’ve done a lot of things, and these machines are basically as good as I am, if not better, at the moment, across many tasks. There’s a real question in my mind about whether we should be teaching people how to program computers at all, right? I actually think we should, and I’m not arguing against it, but I think it’s at least a reasonable question to ask given the fact that it is extraordinary what can be created by a person without technical expertise.

To give you an example of this, I spent some time in a previous rendition of myself working with the ALS community, and I befriended a person who’s an amazing human being named Steve who has ALS. Steve uses a piece of software, which is called Dasher, that was written in a computer programming language that basically doesn’t really exist anymore, like 30 years ago. And it’s his primary communication, and he was always bothering me to fix the code for him so that it could do more things. Steve emailed me the other day, and to be clear, Steve types with his eyes — if he’s listening to this, hi, Steve. He emailed me the other day that he’s now using GPT-5 to fix the code himself. I think that we’re just living in a different world and that we need to rethink what the goals of education are, what we’re trying to teach people so that they can actually innovate.

Laine Perfas: I feel like each of you have mentioned in various capacities, we should let the machines do the things that they’re really good at and also focus on the value of the human. And one of the things that I keep coming across is we learn from each other so much, the value of the teacher in a young student’s life, or Michael, thinking about how you redesigned your class. And part of it was to have students explain to you what they did and how they came up with it. So I’d love to talk about how you see an opportunity for things like chatbots to be there for instruction, while also not losing that critical human-to-human interaction.

Grotzer: There was a piece in the Chronicle where a student was asking the writer about use of AI, and he had written an essay and he showed the feedback that he had gotten from his professor to this writer. And he said, “I used AI to write my essay.” And the writer said, “Yes, I can see that.” And then he said, “But look at the feedback I got from my professor.” And the writer looked at it and said, “And you know that your professor used AI to respond to you?” It was beautiful feedback if you looked at what was given, but it wasn’t feedback that was going help anyone because it wasn’t about anything that someone had generated. So, you know, the machines are talking to the machines at that point. And then we’ve truly lost the purpose of education. The social piece is so important and that ability for two minds to really grapple with something. The other thing we know from the tutoring research is that what good tutors do is they manage motivation and they give information in certain ways while constantly managing the social-emotional context and the kinds of things that we might expect a tutor to respond with. They might not fill in the information. They might just let it sit there. They might let someone get to a certain level and hold back, and then the next time they might come to that level. AI isn’t like an expert human tutor. That social piece of really knowing the social-emotional component is critical.

Xu: I would agree with that. I think AI could do a really good job in generating the kinds of information that is very similar with what humans could provide. But learning is much more than just exchanging information and receiving feedback. And there is this relationship-building piece in the learning process that is very difficult to be replaced by AI. In my own studies, I looked at how much kids learn from an AI tutor versus a human tutor, although sometimes I do find that the learning outcomes are similar, just the amount of information the kids are able to retain was similar across the different learning formats. But kids reported that they had a higher level of enjoyment when they talked to a human tutor. Also, throughout observation, they are just more animated and more engaged in the entire learning process. It does improve the kids’ interest in learning, their confidence, their communication. Those are the aspects that are very difficult to be replaced by AI. In my own class, I did a small experiment with my students to understand the kind of social aspects in learning. We gave them identical essay feedback, but I just told one group of students, “This is the essay feedback generated by an AI,” and the other group of students, I told them, “This is your feedback generated by me,” but they looked at exactly identical feedback. I asked them to tell me, “How useful do you think the feedback is?” And just knowing that the feedback coming from an instructor actually significantly increased students’ perception of the usefulness of the feedback. What really matters is not only the kind of information students receive, but they know that the instructors really care about them and want them to succeed. I think that is a very useful ingredient in learning.

Grotzer: The way that we structure schools — I think about middle schools and high schools where, so many kids are coming through a classroom that teachers don’t have good time to really get to know each one. As we think about this shift in purpose of education, that’s something else we could be thinking about a shift in. Because a good teacher is holding so much social-emotional information about a student. They’re balancing motivational factors with cognitive factors. They are giving very subtle hints to get somebody to think about stuff without giving it away. They often escalate how much support they’re given so that a student doesn’t totally fail, so that they walk away with some sense of success and that they can take on something the next time. As we rethink schooling in the age of AI, we should be rethinking how we enable the context that allows teachers to get to know their students deeply and well. I have young people in my household, some who went to large, urban public schools and didn’t really feel so known. And I have some who went to little tiny schools, six kids in your graduating class or 20 in your graduating class. And that difference of really feeling known, it reverberated throughout their early adolescence and how they felt about themselves, how they felt about grownups. Those relationships are holding environments as kids launch into what’s been called the rocket years, you know, the years in their 20s as they’re establishing careers and their own sense of competence in the world. I think we should be rethinking the structures of schools to accommodate these very kinds of social relationships that you’re talking about, Sam.

Laine Perfas: Thinking about everything we’ve talked about at the end of the day, the goal here is to think through how we put guardrails in place so that we can protect and foster the next generation of thinkers, whether it’s Michael’s camp of using AI to bring the sciences further than they’ve ever been before, but also making sure that we are protecting the relational, emotional, critical-thinking component of learning that’s so vital. So, as we close, what should educators be thinking about when they think about their classrooms and incorporating tools, and what should parents be thinking about when they’re having conversations with their children about the purpose and role of AI in their life?

Brenner: What I think about, is: Can I prove or measure that students are learning more by the use of tools? I think people should be experimenting and trying and just see what works and what doesn’t. But I think what’s very important in that type of an environment is to have some way of actually measuring that it’s working, because in the end, it really does matter if we’regoing to change the way people are educated.

Grotzer: One of the things that I think is so important for young people coming up through our educational system is that they have a sense of agency about their learning and they feel empowered to use it and to use it well. AI is going to be a part of that. Sometimes you might see limits on your use of it in certain ways, but that is in service of protecting your ability to learn and use your mind well in the future to be able to achieve your goals out in the world. What is your moonshot? How do you want to see your contribution to the world? How can AI and your amazing mind work in service of that? For that reason, sometimes in educational contexts we might put guardrails, but those guardrails are really ones that are in service of your future abilities.

Xu: What I would add is that I think AI is very important, but there are also many other things going on in young people’s lives that are equally important. So if we zoom out, it’s likely AI could be a good resource, but there are so many other opportunities and experiences kids are engaged in. For example, like their families, their friends, their time spent on their hobbies, and time in nature. Those are very important things that are playing a role in shaping children’s development. From a kind of a broader bird’s-eye view, AI probably doesn’t matter as much in isolation. What does matter is how it fits into the larger ecosystem of a child’s life. So maybe this is a message to parents and educators, and yes, it’s important to think about AI, but don’t forget that there are many other things in your child’s world that matter just as much.

Laine Perfas: Thank you all for joining me for such a great conversation.

Xu: Thank you, Sam. This was really fun.

Grotzer: Thank you for the opportunity. It’s been a pleasure.

Laine Perfas: Thanks for listening. For a transcript of this episode and to listen to our other episodes, visit harvard.edu/thinking. If you’re a fan of this podcast, rate and review us on Apple and Spotify. It helps others discover us. This episode was hosted and produced by me, Samantha Laine Perfas. It was edited by Ryan Mulcahy, Paul Makishima, and Sarah Lamodi. Original music and sound design by Noel Flatt. Produced by Harvard University, copyright 2026.

Recommended reading

- “When you do the math, humans still rule” by The Harvard Gazette

- “Is AI dulling our minds?” By The Harvard Gazette

- “The Impact of AI on Children’s Development” by Harvard EdCast