Can a chatbot be a co-author?

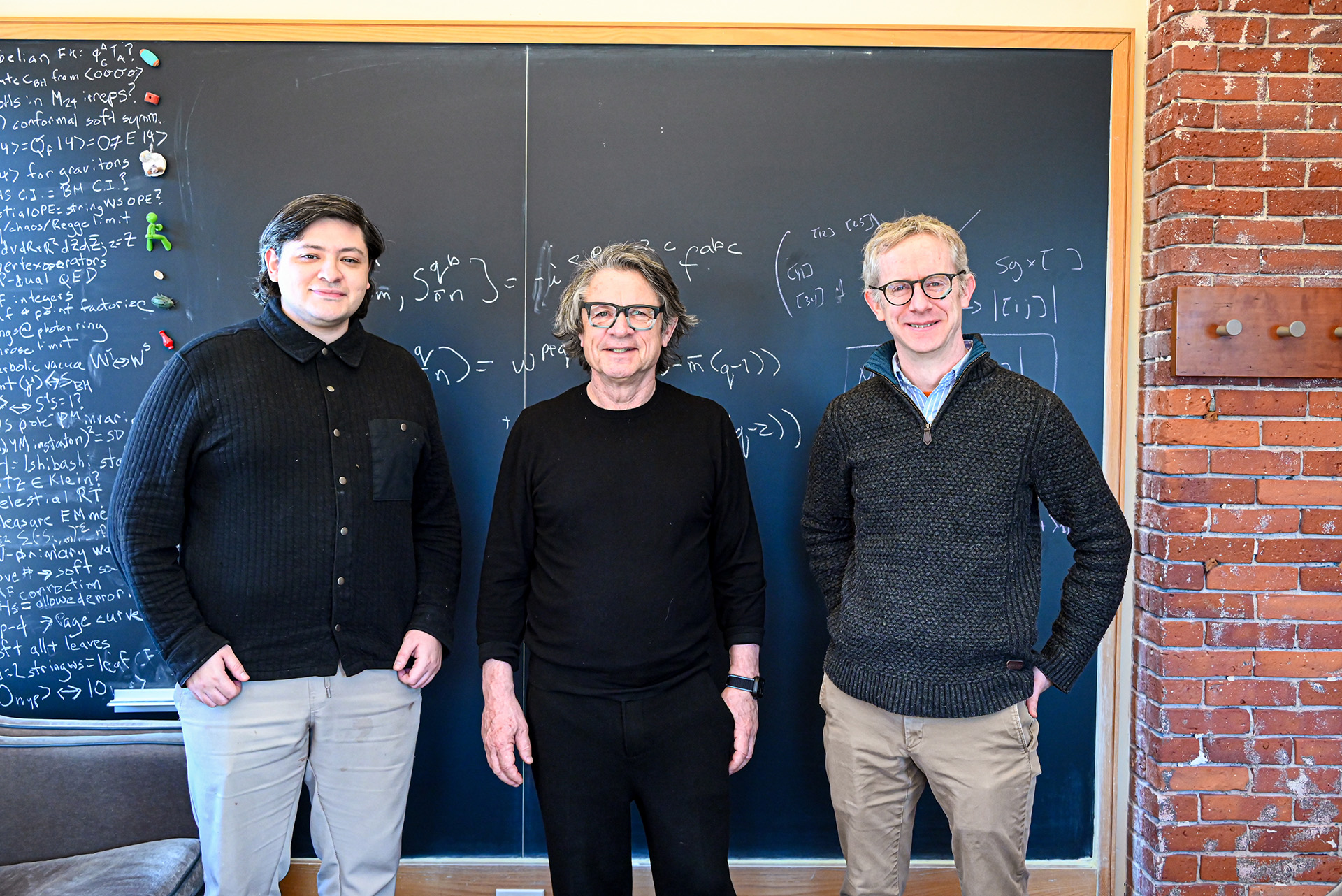

Alfredo Guevara (from left), Andrew Strominger, and David Skinner.

Photo by Jeffrey Yang ’26

Physicists take souped-up ChatGPT out for a spin, return home with significant discovery

Like many scientists, theoretical physicist Andrew Strominger was unimpressed with early attempts at probing ChatGPT, receiving clever-sounding answers that didn’t stand up to scrutiny. So he was skeptical when a talented former graduate student paused a promising academic career to take a job with OpenAI. Strominger told him physics needed him more than Silicon Valley.

Still, Strominger, the Gwill E. York Professor of Physics, was intrigued enough by AI that he agreed when the former student, Alex Lupsasca ’11, Ph.D. ’17, invited him to visit OpenAI last month to pose a thorny problem to the firm’s powerful in-house version of ChatGPT.

Strominger came away with much more than he expected — and the field of theoretical physics appears to have gained a little something too.

“Incredible,” Strominger put it, acknowledging that AI quickly reasoned through a problem he wasn’t sure he could solve himself without unlimited time.

Strominger had carefully chosen a problem that had eluded concerted collaborative efforts at solving but was understood well enough to clearly post to AI.

Neither scientist expected a breakthrough.

Even Lupsasca, who has served as a research scientist at OpenAI since last fall, imagined the problem would probably trip up the AI, giving them an opportunity to provide feedback and help improve the large language model’s reasoning around complex theoretical physics.

Instead, the internal ChatGPT — what Strominger dubbed “Super Chat” — eventually solved the thorny problem in its entirety.

Four physicists — Strominger, Lupsasca, Cambridge University’s David Skinner, and the Institute for Advanced Study’s Alfredo Guevara (who had worked with Strominger as a junior fellow in the Society of Fellows from 2020-2024) — worked with ChatGPT as a powerful fifth collaborator.

ChatGPT-5.2 pro broke the logjam, proposing an answer, and Super Chat proved it was correct after 12 hours of running.

The group then spent a week breaking down the solution, checking the calculations by hand, and turning it into a paper, the result of which (“Single-minus gluon tree amplitudes are nonzero”) published as a preprint on arXiv.

“I think AI will empower us to do more, but we have to retool. Good scientists have to retool all the time.”

Andrew Strominger

While the specific findings will interest what Strominger called “the cognoscenti in some sub-field of theoretical physics,” the broader takeaway for those without a physics Ph.D. requires no fluency with gluon amplitudes.

“It’s the first significant discovery in theoretical physics that is done by an AI,” said Lupsasca, who is also a former junior fellow.

“Maybe we’d have figured out a clever trick the next day,” Strominger said about the efforts of the team of physicists. “Maybe we’d have never gotten it.”

The scientists collaborated using both the publicly available ChatGPT-5.2 pro and the in-house Super Chat, which can “think” through complex problems for 12 hours at a time.

Strominger found the experience exhilarating.

“There was a moment when I felt like I was working with a creative person,” he said. “Not just a machine that was crunching through stuff. You know, that’s all psychological, but it felt that way.”

Strominger typically works on three or four problems at a time, progressing incrementally but steadily. In this case, though, he had stalled while attempting to prove a conjecture about gluons, the particles that mediate the strong force binding the nucleus of an atom together.

Amplitudes are the complex quantities used in quantum mechanics to provide probabilities for the outcomes when atomic particles interact. Physicists sometimes presumed a certain kind of gluon amplitude could not exist. Strominger, Skinner, and Guevara thought otherwise.

Guevara worked out an exceedingly complex expression of these amplitudes, but they could not finesse it into something simple. They even tried feeding it into ChatGPT last spring, without success.

“It just fumbled,” Strominger said. “The latest model is a whole new ballgame.”

Enter Lupsasca, who had recently transformed from skeptic to proselyte.

A year ago, having tried only the free version of ChatGPT, he considered it useful mainly for proofreading grant proposals. Then he got stuck trying to find a solution to a differential equation describing magnetic fields around pulsars.

“Usually in this game, there’s always some trick that you have to pull out of a hat,” a “special identity,” or formula, to unlock the answer, he said.

A friend with a subscription to the pro version of ChatGPT-3 suggested he feed it an experiment. In 11 minutes, it solved the problem using a special identity published in an obscure Norwegian mathematical journal in the 1950s. (Still, it made a very “human” mistake, resolving the hard part but adding a typo to the answer.)

Last June, Lupsasca published a paper after deriving new black-hole symmetries, what he called “one of my coolest calculations.” He was feeling good — “I can count on my hands the number of people in the world that could have done that” — until he tested out the new ChatGPT-5.2 pro upon its release in August.

In less than 30 minutes, AI crunched through calculations that had taken him considerable time and brainpower.

“That’s when I became ‘AI-pilled,’ as people say,” Lupsasca said, determined to join the vanguard of what he called “the most significant change in theoretical physics in my lifetime.”

He reached out to OpenAI, which had prioritized the model’s ability to transform coding but hadn’t taught it to work on complex physics problems.

ChatGPT simply learned while absorbing oceans of information. So the company accelerated the launch of OpenAI for Science, a program to hire specialized faculty to reinforce ChatGPT’s reasoning, starting with math and theoretical physics.

In October, they made Lupsasca their first hire; he took leave from the faculty at Vanderbilt and made his mentor Strominger his first invitation to test ChatGPT.

Since Strominger’s return to campus, people have asked whether AI might render him obsolete.

“Call it vanity. I think I’m irreplaceable,” he mused. “I think it’s just the opposite. I think it will empower us to do more, but we have to retool. Good scientists have to retool all the time.”