Want to speed brain research? It’s all in how you look at it.

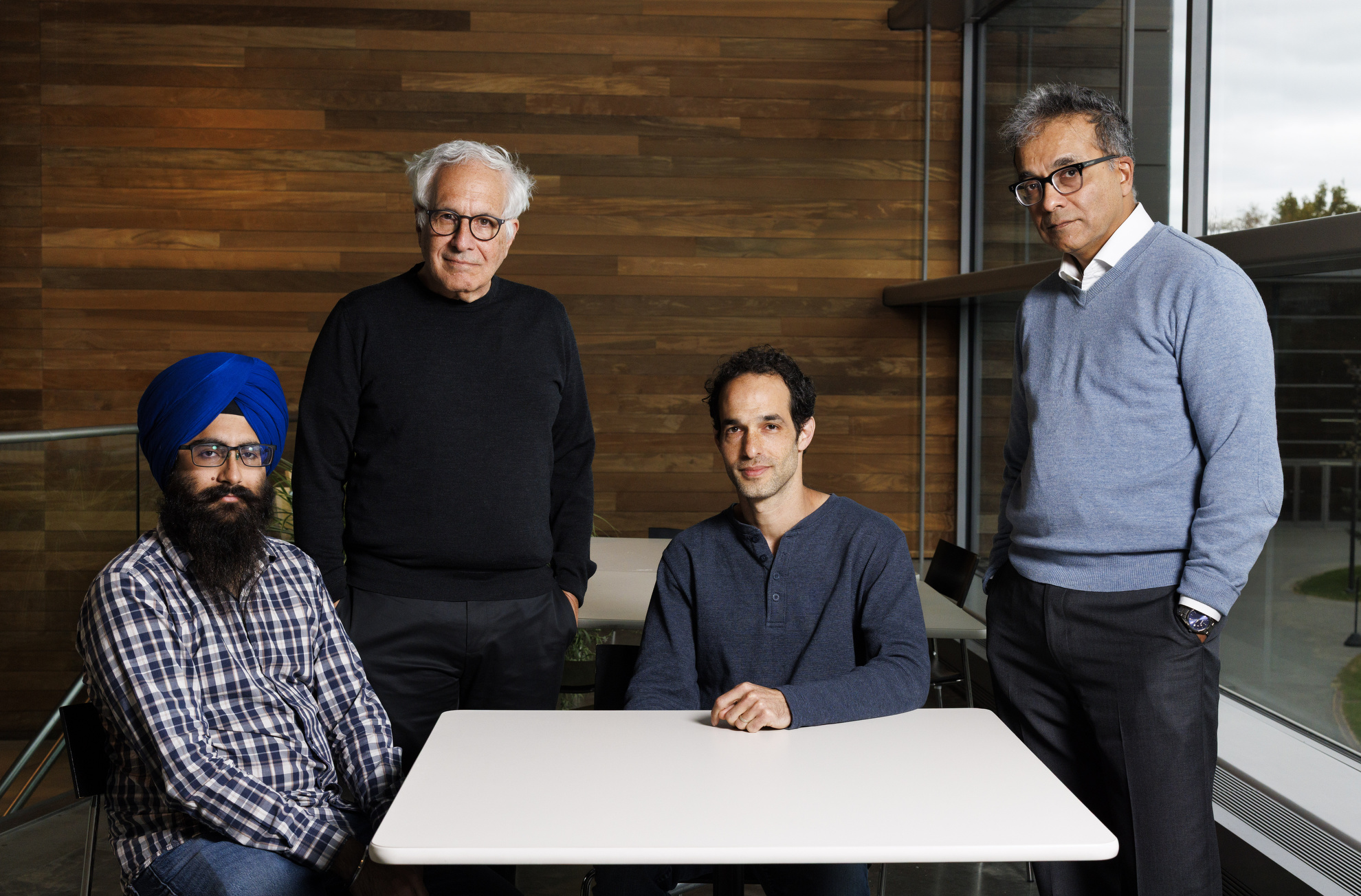

Ishaan Chandok (from left), Jeff Lichtman, Yaron Meirovitch, and Aravinthan Samuel.

Veasey Conway/Harvard Staff Photographer

New AI-enhanced scanning method promises to boost quest for high-resolution mapping

To get a better look at brains, Harvard researchers are making microscopes work more like human eyes.

Until recently, the quest to build high-resolution maps of brains — otherwise known as “connectomes” — was stymied by the slow pace and cost of powerful electron microscopes capable of systematically capturing neuroanatomy down to billionths of a meter.

But now a team of scientists at Harvard and MIT have found a way to bypass that bottleneck: using machine learning to guide a simpler, less-expensive variety of microscope in real time. The idea is to home in on key details first and minimize time spent on areas of lesser interest — the same way we might zero in on words on a page instead of margins.

Researchers say the innovation, known as SmartEM, will speed scanning sevenfold and open the field of connectomics to a broader research community, boosting our understanding of brain function and behavior.

“SmartEM has the potential to turn connectomics into a benchtop tool.”

Aravinthan Samuel

“SmartEM has the potential to turn connectomics into a benchtop tool,” said Professor Aravinthan Samuel, a researcher in the Department of Physics and Center for Brain Science and one of the senior authors of a new paper published in Nature Methods. “Our goal is to democratize connectomics. If you can make the relatively common single-beam scanning electron microscope more intelligent, it can run an order of magnitude faster. With foreseeable improvements, a single-beam microscope with SmartEM capability can reach the performance of a very expensive and rare machine.”

The method is the product of a five-year collaboration between researchers at Harvard, MIT, Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, and microscope manufacturer Thermo Fisher Scientific.

In December, the same journal proclaimed electron microscopy-based connectomics its “Method of the Year” for 2025 and cited SmartEM an example of cutting-edge innovation.

SmartEM marks a new advance in the decades-long quest to create “wiring diagrams” of brains from across the animal kingdom, from worms to fruit flies to humans.

For example, two years ago Harvard researchers published the first nanoscale map of one cubic millimeter of human brain. Packed into that poppy-seed-sized sample were 150 million synapses, 57,000 cells, 230 millimeters of blood vessels, and a wondrous diversity of structures never seen before.

Researchers elsewhere have completed connectomes for the fruit fly and zebrafish. The next grand challenge is one for the mouse.

To build these maps, scientists have relied on a technique known as serial-section electron microscopy. It entails shaving samples of brain tissue into thousands of ultra-thin sections, which are then scanned and imaged by powerful electron microscopes.

Next the images are stacked on top of each other to create 3D digital replicas. For example, that one cubic millimeter of human brain tissue published in 2023 was sliced into more than 5,000 sections, each thinner than one-thousandth of a human hair.

These endeavors pose monumental technical hurdles for both capturing the images and processing the data.

Until recently, connectomics had been the exclusive purview of a small number of researchers and institutions that can afford multimillion-dollar hardware such as high-throughput electron microscopes with up to 91 beams.

With growing demand to generate brain maps of many species, one obvious way to push forward connectomics is to recruit more microscopes — particularly single-beam electron microscopes, which are widely available at research institutions around the world.

Their speed largely is a function of the “dwell time” that the beam devotes to each pixel. In the standard approach, specimens are scanned with the same high resolution for all pixels.

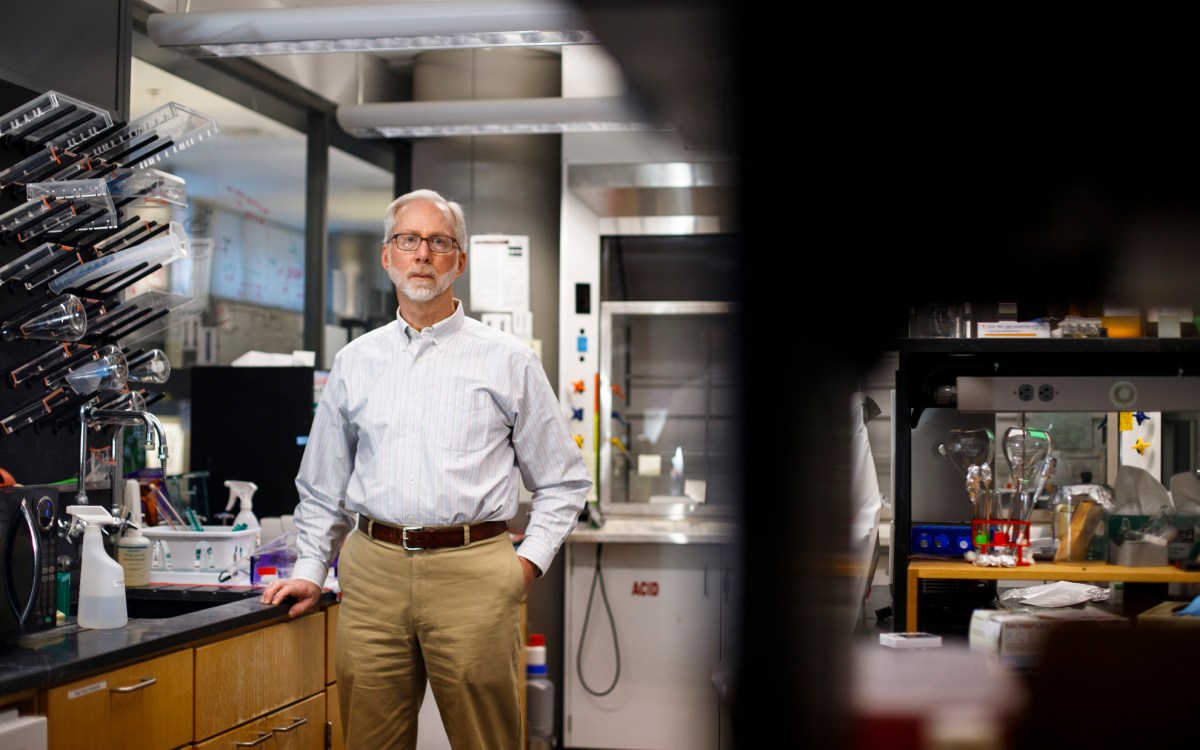

“We usually shoot the picture first and then we aim.”

Jeff Lichtman

“We usually shoot the picture first and then we aim,” said Science Dean Jeff Lichtman, Jeremy R. Knowles Professor of Molecular and Cellular Biology and Santiago Ramón y Cajal Professor of Arts and Sciences, a co-author of the new paper. “From the data that you’ve shot, you then look at the particular things that you find interesting. And that’s not the way our eyes work.”

Instead, people focus their attention on key details such as the eyes and mouths of other faces or a fly on the wall instead of the larger white background.

“This is similar to what we are doing,” said Yaron Meirovitch, chief architect of SmartEM and the lead author of the new paper. “The machine learning and microscope are taking a fast image, getting a sense of where are the important parts, then going there and dwelling longer, until it understands what it is seeing.”

“The machine learning and microscope are taking a fast image, getting a sense of where are the important parts, then going there and dwelling longer, until it understands what it is seeing.”

Yaron Meirovitch

The new system uses machine learning to transform single-beam machines into “smart” microscopes.

First, the microscope performs a rapid, low-quality scan of the entire sample. Then a neural network analyzes the image and identifies key features of interest — such as synapses in brain tissue — or error-prone regions. Only these regions are scanned at high resolution and longer dwell times.

Finally, SmartEM uses an algorithm to blend the composite images into a single scan of uniform appearance.

The method demonstrated dramatic improvement in scanning times when tested on tiny brain tissue samples from a worm, mouse, and human.

For example, the SmartEM technique was tested on Caenorhabditis elegans, a roundworm species used four decades ago for the first wiring diagram ever produced. Normally, a single-beam microscope scan of the worm brain and body would require about 1,400 hours, but SmartEM completed the job in only 200.

“The ultimate wiring diagram result is identical,” said Lichtman, “because you’ve only done that slow scanning on the places where it’s not a waste and where you really needed that information.”

That means that mapping brains may move within reach of research institutions that cannot afford multibeam machines with price tags of several million dollars. “It’s part of the notion of democratizing connectomics,” added Lichtman, “and making the field a little more accessible to people who don’t have the deep pockets.”