Updike’s life in letters

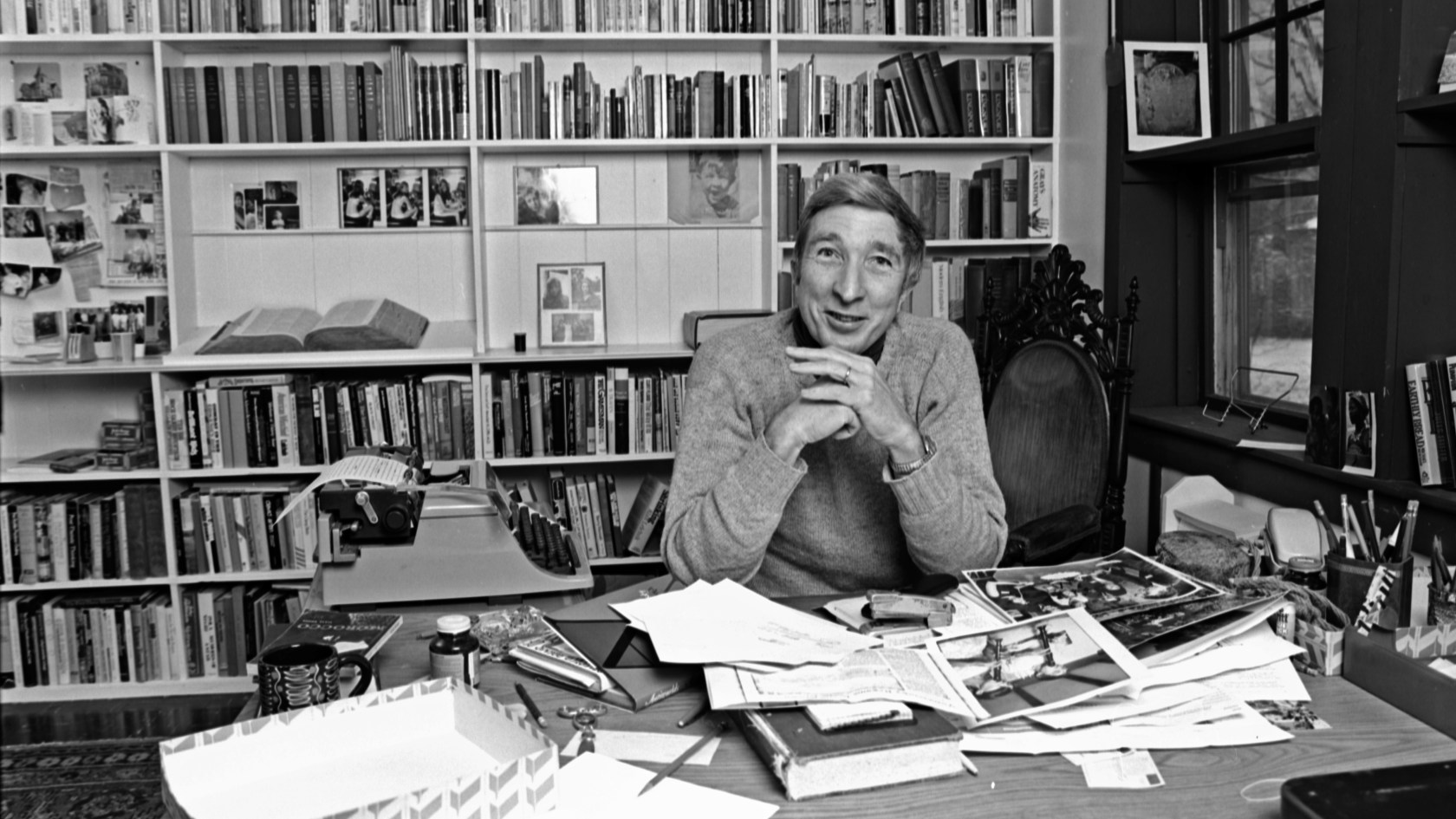

Author John Updike at his home in Massachusetts in November 1978.

Photo by Jack Mitchell/Getty Images

From teen penning fan mail on family farm to Pulitzer Prize-winning author: ‘He needed to write the way most of us need to breathe or eat’

It started with a letter.

In the late 1980s, when James Schiff was a graduate student, he wrote a letter to John Updike ’54, the prominent American literary figure who was the subject of his dissertation and an author he had long admired. A few days later, he received a response in the mail.

“I was astonished,” said Schiff, a professor of English at the University of Cincinnati. “I didn’t even think I would get a response, and not only did I get a response, but given the timing, he probably got the letter on a Tuesday, and then he had the response in the mail to me on Wednesday with all my questions answered.”

Updike, it turns out, wrote a lot of letters. According to Schiff, who recently published the edited book “Selected Letters of John Updike,” Updike wrote more than 25,000 of them in his lifetime. The volume spans 60 years of the writer’s correspondence, which Schiff considers “an integral part” of Updike’s “astonishing literary output.”

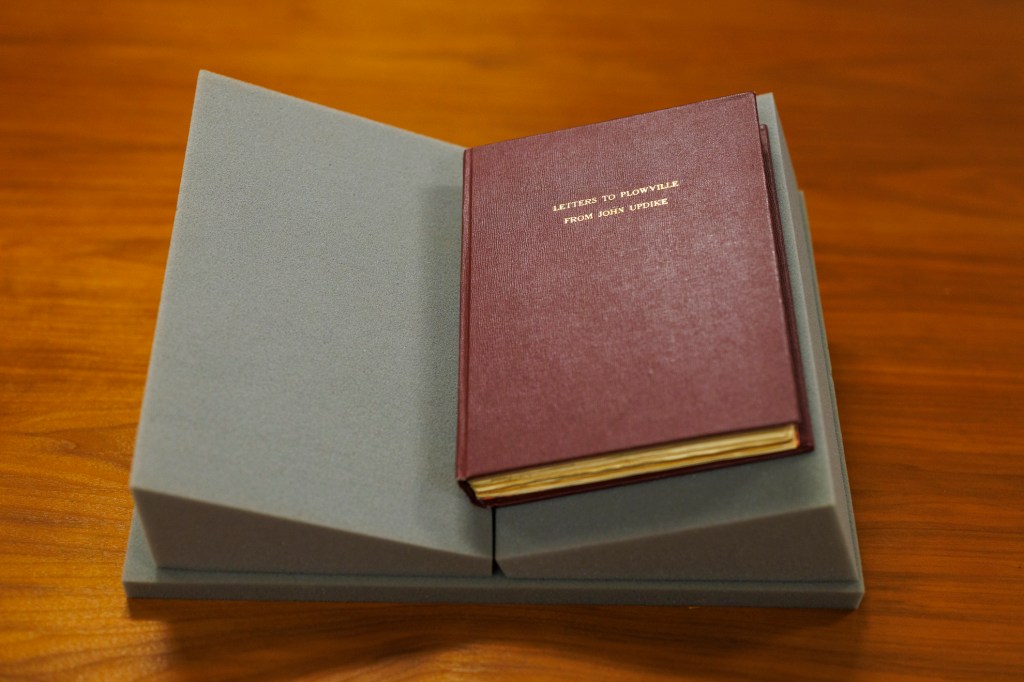

John Updike’s “Letters to Plowville” from Houghton Library’s collections.

Photos by Veasey Conway/Harvard Staff Photographer

A prolific and versatile author, Updike wrote more than 60 books along with nearly 2,000 short stories, poetry collections, and thousands of essays and pieces of literary criticism. He won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1981 and again in 1990 for two novels from his “Rabbit” series. When Updike died in 2009 at age 76, a New York Times obituary called him a “lyrical writer of the middle-class man.”

Updike’s depiction of small-town, middle-class America appealed to Schiff, who grew up in Cincinnati feeling he “needed to live in Hemingway’s Paris or Tolstoy’s Russia.” Reading Updike changed his mind. “Updike made the mundane, quotidian life of middle America so beautiful, interesting, and mysterious,” said Schiff.

Unlike other writers, Updike didn’t keep journals or diaries, said Schiff, who is now working on a biography of the author. Writing letters was common among Updike’s generation and was a way to record what was going on in his life. “He needed to write the way most of us need to breathe or eat,” said Schiff, a cofounder of the John Updike Society and founding editor of the John Updike Review.

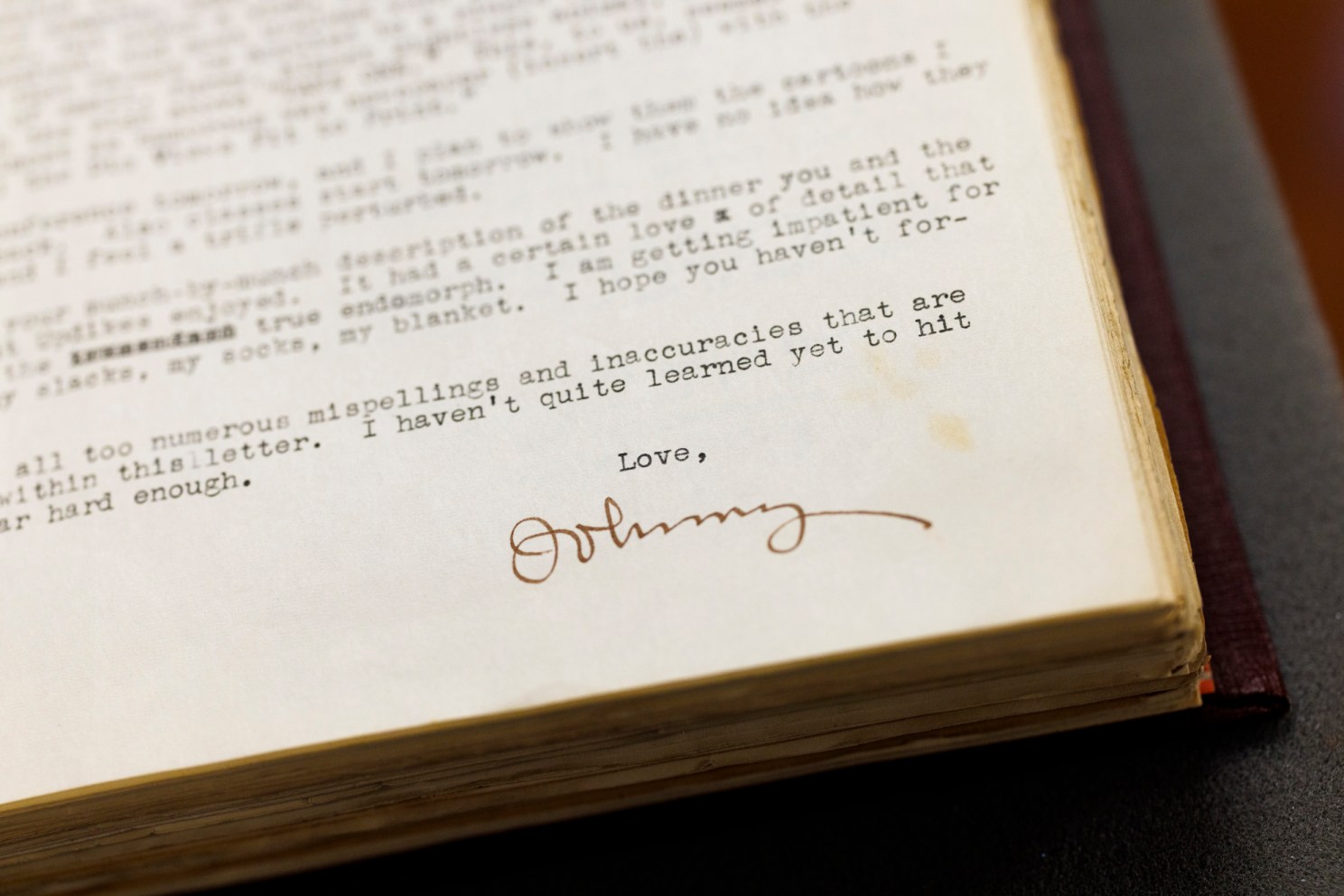

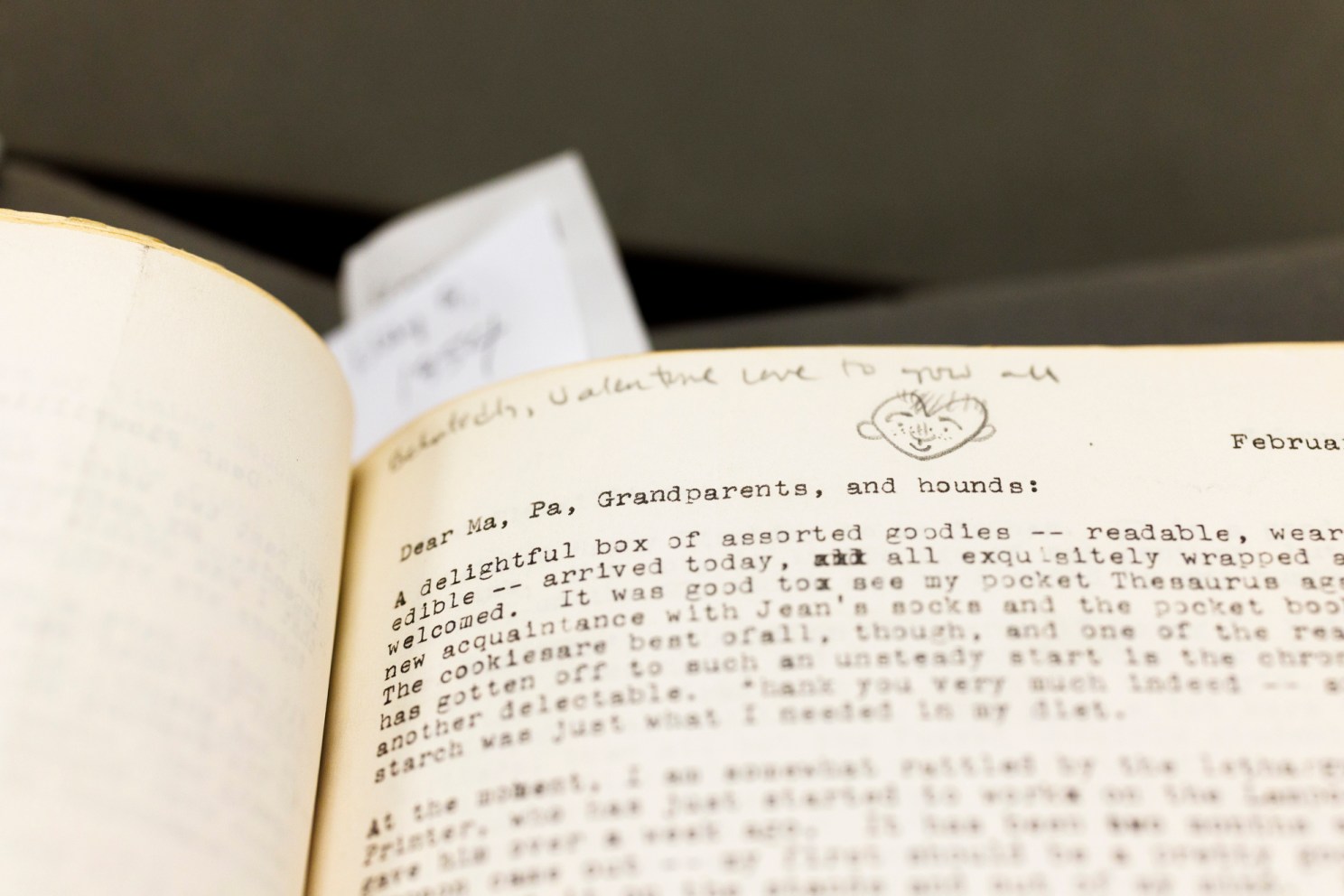

Updike started writing letters as a teen, when he sent fan notes to cartoonists and artists he admired or submissions to magazines from his family farm in Plowville, Pennsylvania. His love for words was inspired by his mother, an aspiring writer. During his years at Harvard, between 1950 and 1954, Updike wrote about 150 letters to his parents about his courses, his roommates, and life in general. His letters from Hollis Hall show a writer with a keen eye and an already precise and refined writing style.

In the first letter he sent home from Harvard, dated Sept. 25, 1950, Updike wrote “Harvard is a difficult place in which to write a letter. … I’m rather frightened by the immensity of intelligence and variety of talents displayed here.” In another letter, a month later, he wrote, “I’m delighted by the way the Yard looks on a sunny day, and the way the front of Widener Library lights up at night. … I revel in the abundance of food, of independence, of thought.”

A detail from Updike’s first letter home from September 26, 1950.

A letter from February 16, 1953.

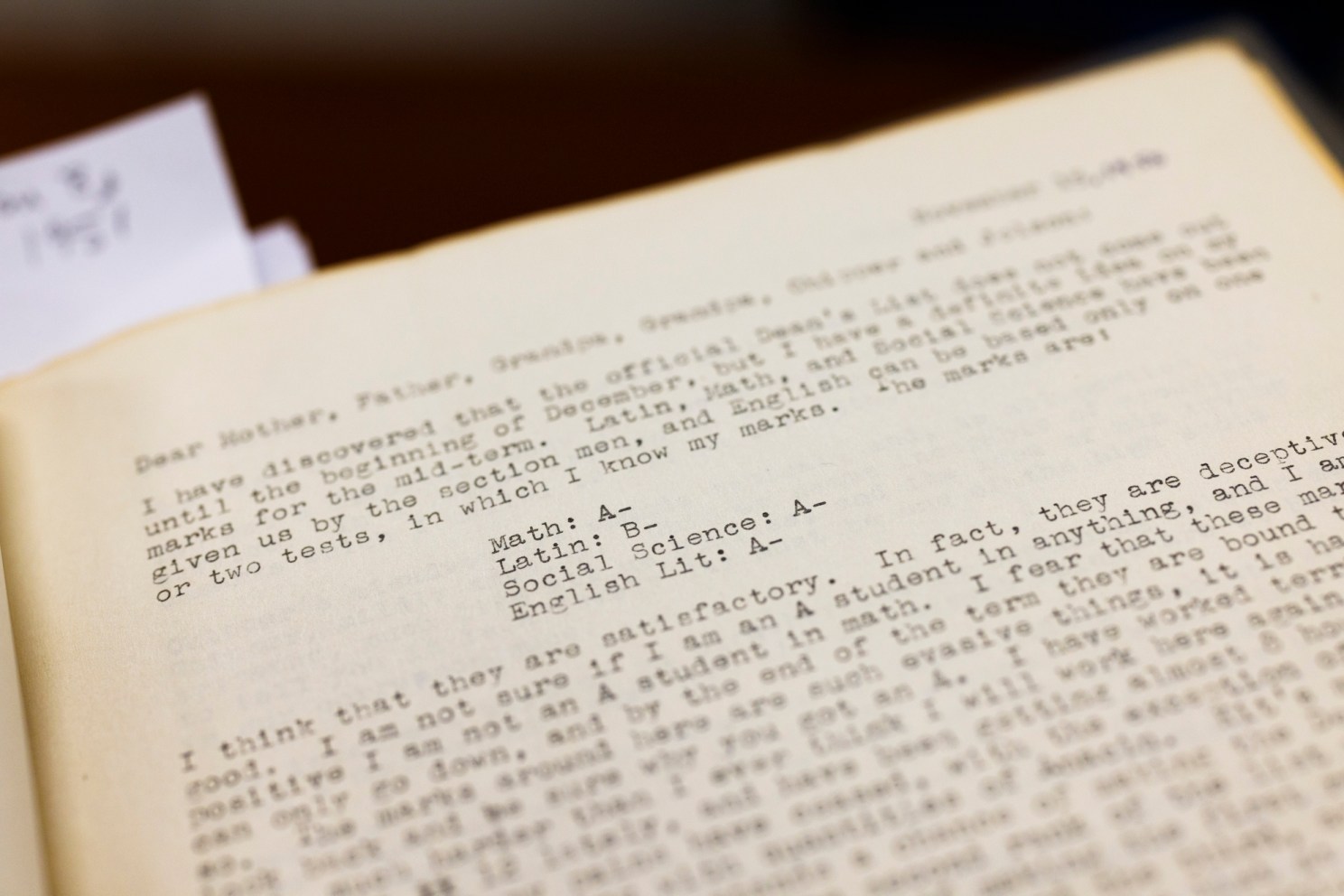

Updike sharing his grades in a letter from November 15, 1950.

In other missives, Updike wrote about the fun he had at the Harvard Lampoon as cartoonist, editor, and president, how sad he was when he was “booted out” of an English class, feeling that “his literary career reached its nadir,” and the joy of falling in love with a Radcliffe student who would become his wife at the end of his junior year. “Harvard is a contradictory place,” he wrote. “Nowhere are you allowed so much freedom and given so little time to enjoy it.”

Schiff said the John Updike Archive at Harvard was “crucial” to his research. Over the years, Updike had donated portions of his papers to the University, and after his death in 2009 Harvard acquired the full collection, which includes manuscripts, personal correspondence including rejection letters, drawings and sketches, articles, and two bound volumes titled “Letters to Plowville” assembled by Updike’s mother. The documents, housed at Houghton Library, represent the largest collection of Updike papers, said Leslie Morris, Gore Vidal Curator of Modern Books and Manuscripts at Houghton.

“Almost all of John’s manuscripts and papers, which are voluminous, are held at Harvard,” said Schiff. “Many of his best letters come from that collection, including those letters written to his family.”

Schiff’s volume includes Updike’s letters to his parents, his first and second wives, his children, friends, writers, editors, and colleagues. It took eight years to complete.

Updike’s letters were “seldom boring or perfunctory,” said Schiff, and not only display the “intellectual finesse, wit, and eloquence found in his fictions and essays,” but also attest to his generosity and conscientiousness.

“For somebody who was an artist of such a high stature, he was remarkably open and generous to others.”

James Schiff

“For somebody who was an artist of such a high stature, he was remarkably open and generous to others,” said Schiff, who over the years exchanged correspondence with Updike and met him on several occasions, including in Cincinnati. “Letters had been so important to him as a teenager, when he wrote fan mail to cartoonists he admired … Perhaps because of those cartoonists who were kind to him when he was a teenager, he felt a need to respond to people who wrote to him. I think that was part of his conscientious nature. For the most part, the volume of his letters indicates he enjoyed writing to people.”