The stories behind the books

Photos and video by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Harvard’s libraries hold volumes whose worth goes beyond their words

Books — thousands of which line the shelves of Harvard libraries — allow readers to hold vast knowledge in their hands. But there are some books in Harvard’s collection that take the experience to the next level.

The Gazette, with the help of Harvard librarians from Houghton and Frances Loeb libraries, explored a handful of titles that bring their subjects off the page.

Layers of knowledge

Older than Houghton Library itself, “Catoptrum Microcosmicum” or “Mirror of the Microcosm” is a medical textbook published in 1619 by the German physician Johann Remmelin. Perhaps intended for curious laypeople interested in anatomy, or medical students familiarizing themselves with the human form, Remmelin’s book features dozens of ornate drawings of human bodies.

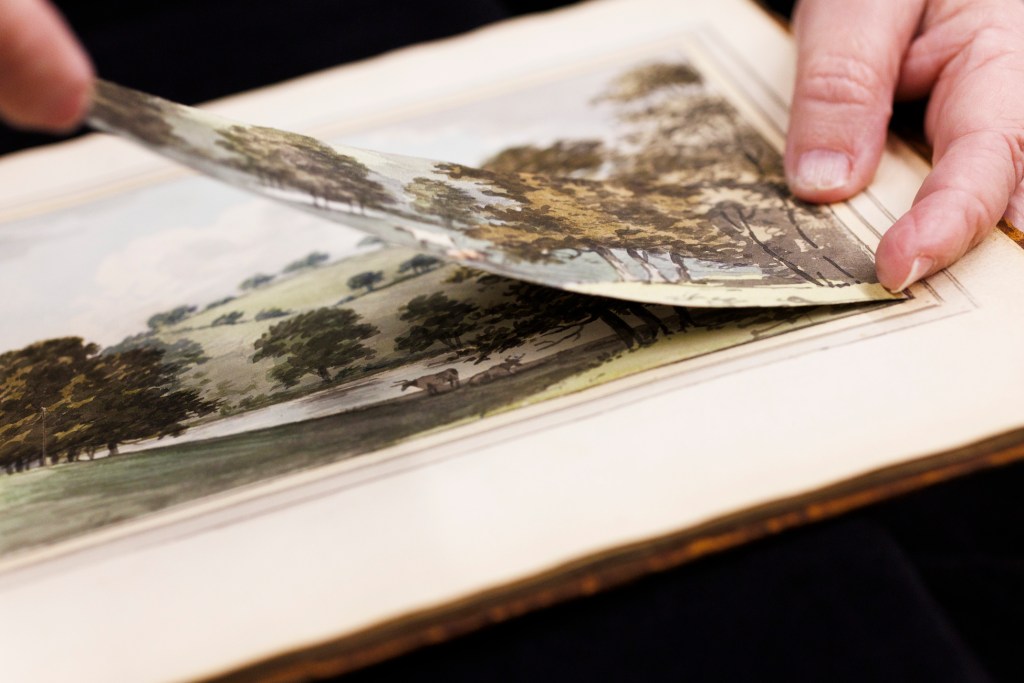

Before and after

Similar to Remmelin’s book, English landscape designer Humphrey Repton created hundreds of books that feature layered images — capturing the before and after of proposed landscape changes for homeowners to preview his work. In Harvard’s collection are design proposals for the Prince of Wales and his Brighton estate as well as the proposal for Mosely Hall near Birmingham — residence of wealthy Englishman John Taylor. Repton created more than 400 of these works throughout his decades long career spanning the late 18th century into the early 19th.

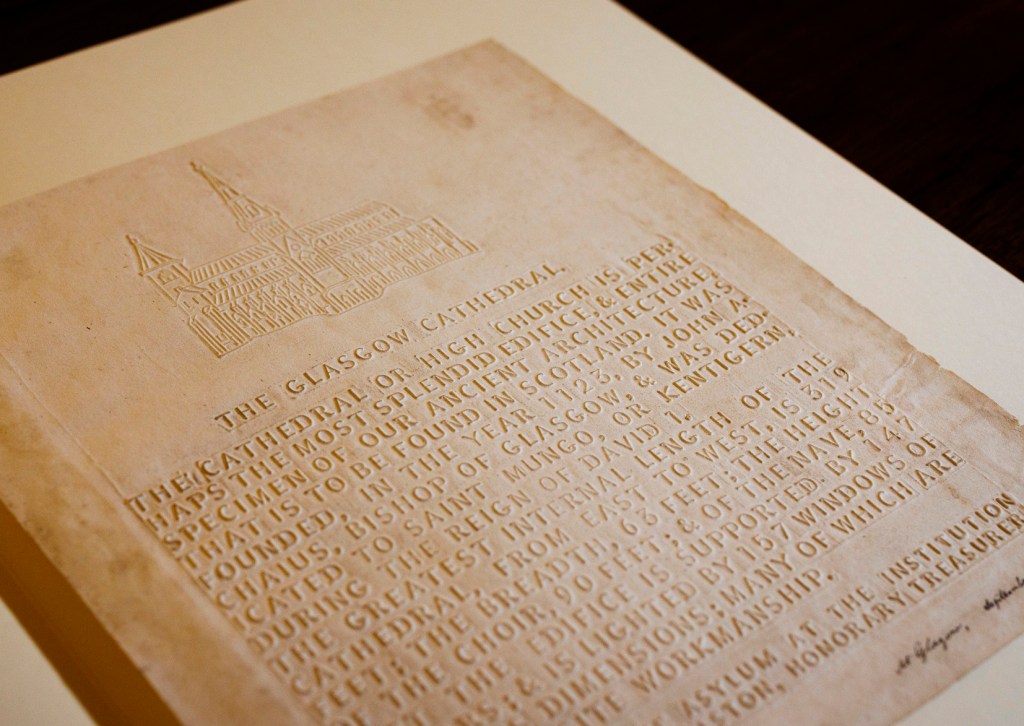

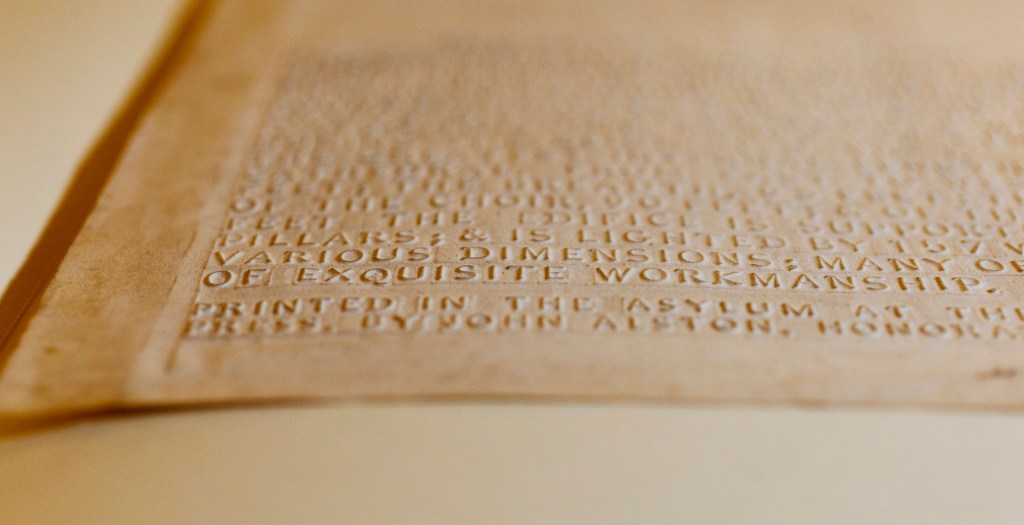

Early books for the blind

Harvard’s libraries also have several examples of books designed to be accessible for blind and visually impaired readers.

Before braille, other systems of type were developed, including “Alston Type” — a system of raised Roman alphabet letters invented by Glasgow Asylum for the Blind director John Alston in 1838. “The Glasgow Cathedral,” published around 1840, is a broadside printed in Alston type with an embossed vignette of the Glasgow Cathedral. The text describes the cathedral as “perhaps the most splendid edifice, & entire specimen of our ancient architecture, that is to be found in Scotland,” giving details about its foundation and physical dimensions.

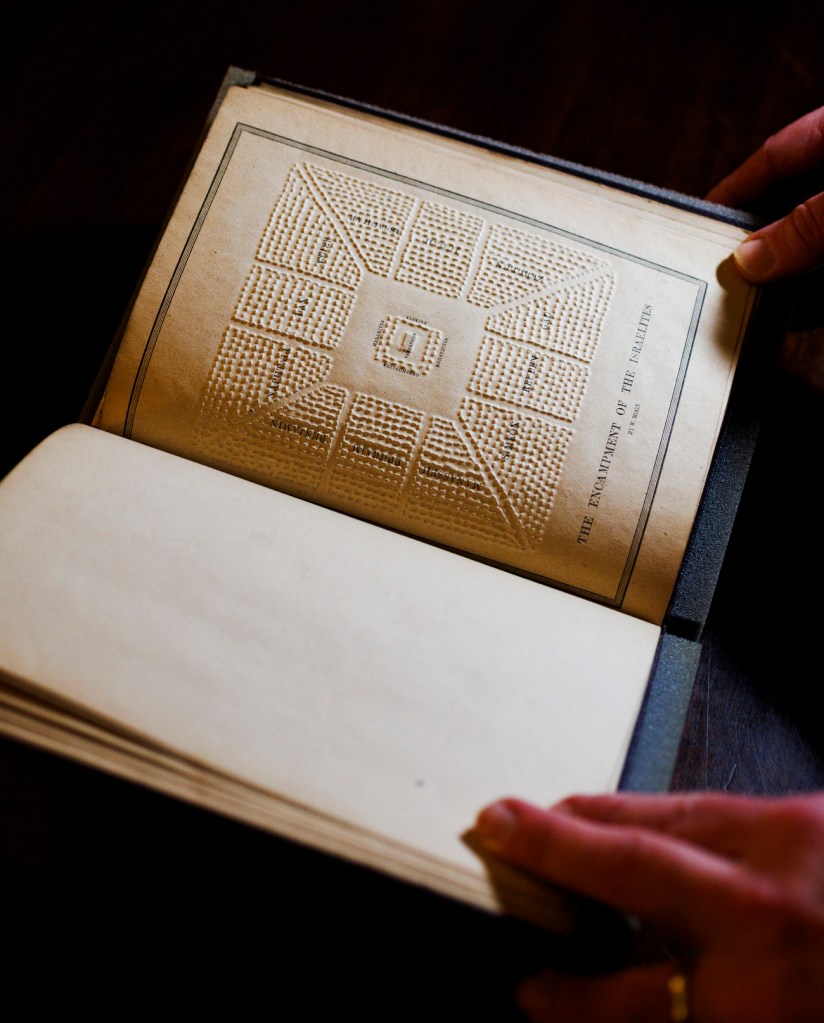

Another braille predecessor was the Moon alphabet invented by William Moon in 1847. Moon, who lost his sight later in life, loosely based his characters on the Roman alphabet, while also incorporating divergent symbols to represent sounds. Throughout his career, more than 300 works were published in Moon type including “Moon’s Biblical Atlas” from the 1870s representing locations from the Christian Bible.

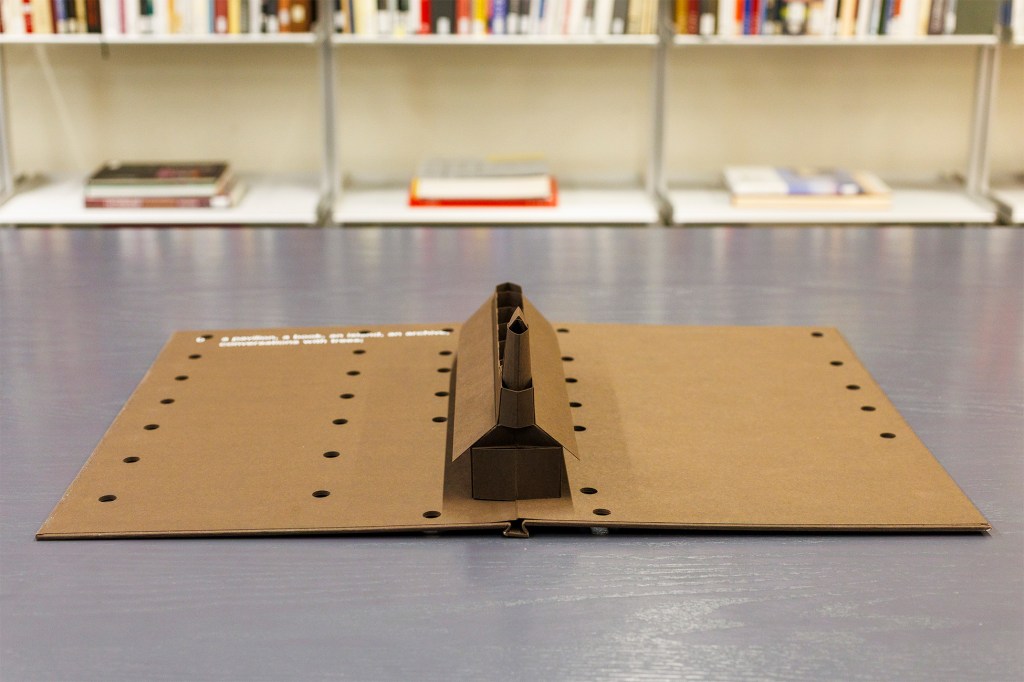

A handheld memorial

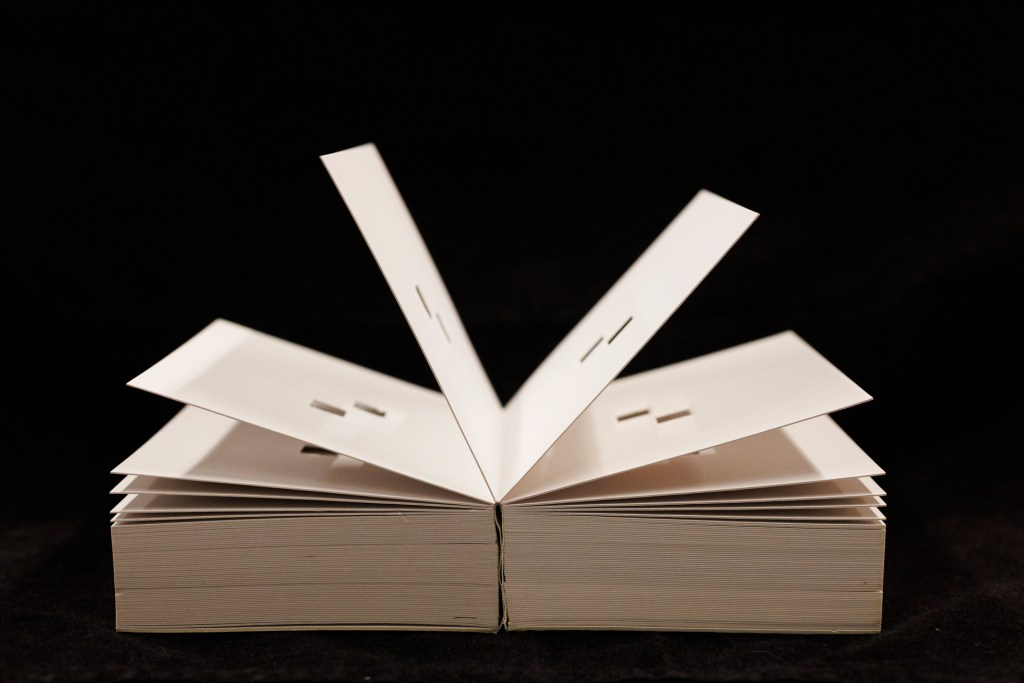

“Absence,” published in 2003, is a memorial of the Twin Towers World Trade Center by architect and designer Jeannie Meejin Yoon. Each of its 120 cardboard pages represents a story of the towers, including the antenna mast.

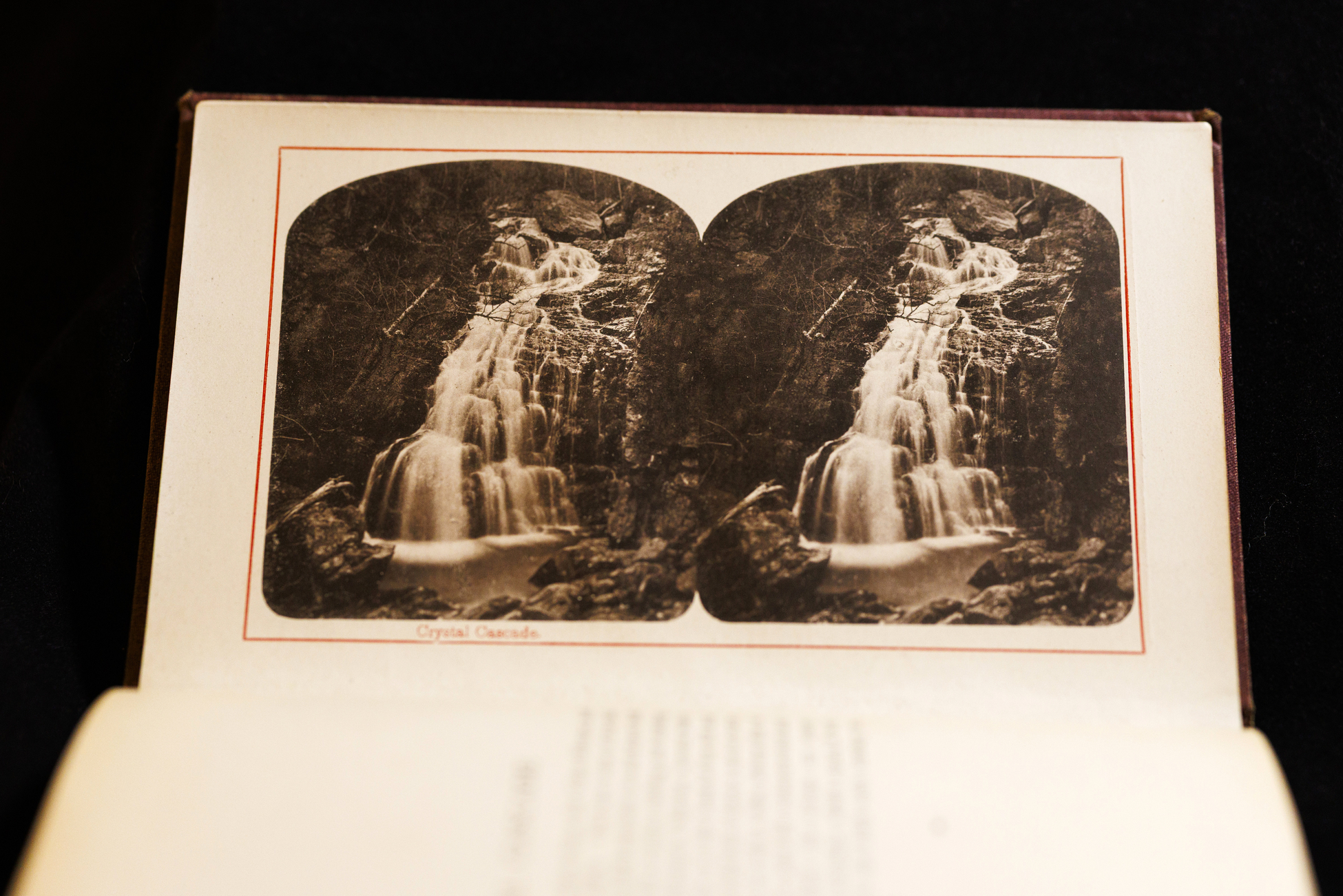

No need to travel

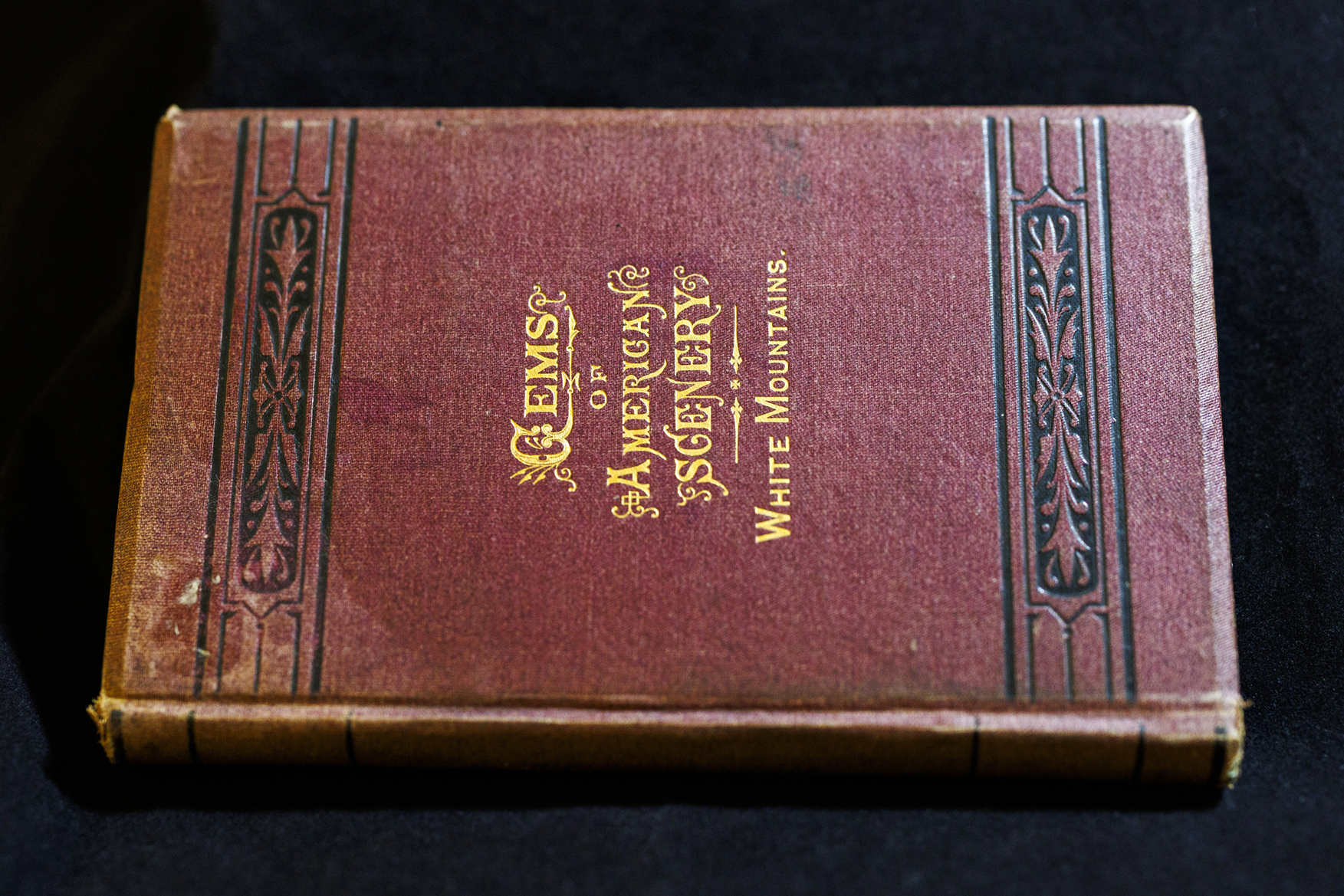

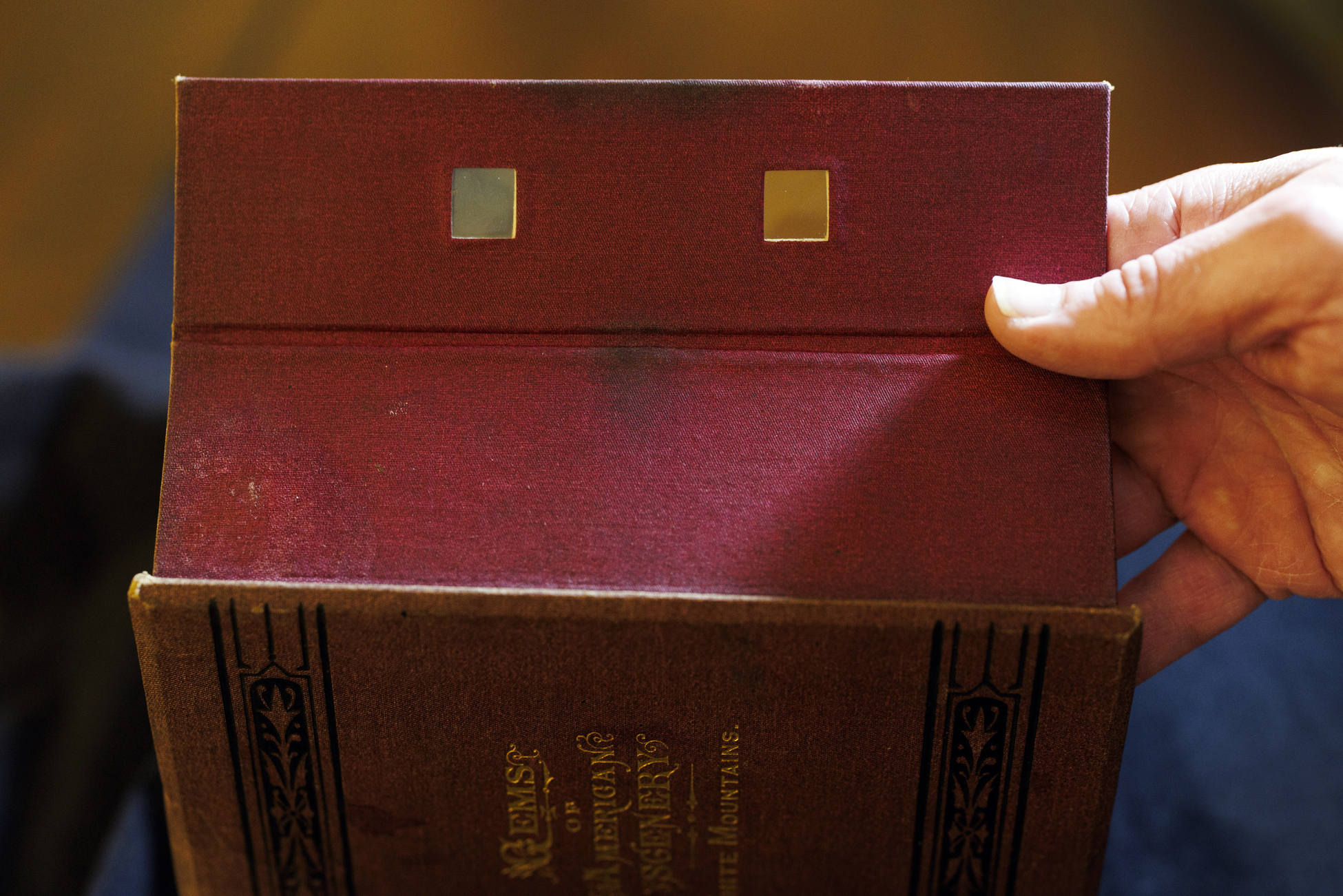

Travelers, mountaineers, and nature lovers in the Victorian era looking to remember their New Hampshire vacation or experience the splendor of the landscape from the comfort of their own home would be able to do so through “Gems of American Scenery.”

Two images align in a stereoscopic viewer to create the illusion of three-dimensionality.

Graphic by Judy Blomquist/Harvard Staff

The book, produced by well-known brothers in commercial photography at the time, Charles and Edward Bierstadt, provides stereoscopic views of the White Mountains — a process in which two photographs taken at slightly different angles are viewed together through a special lens, creating an almost 3D effect.

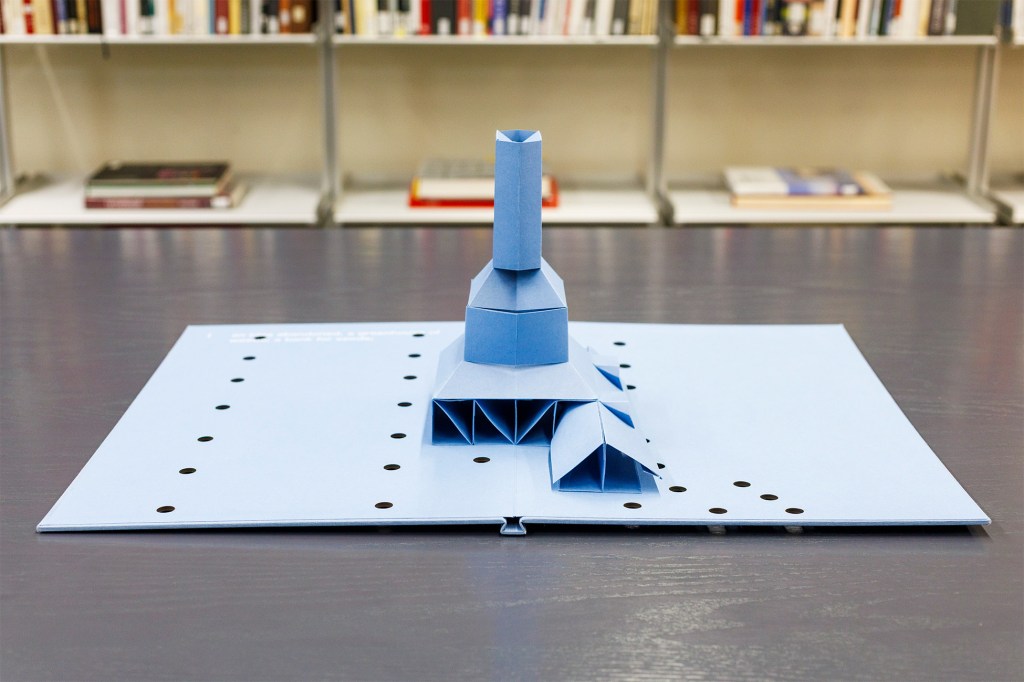

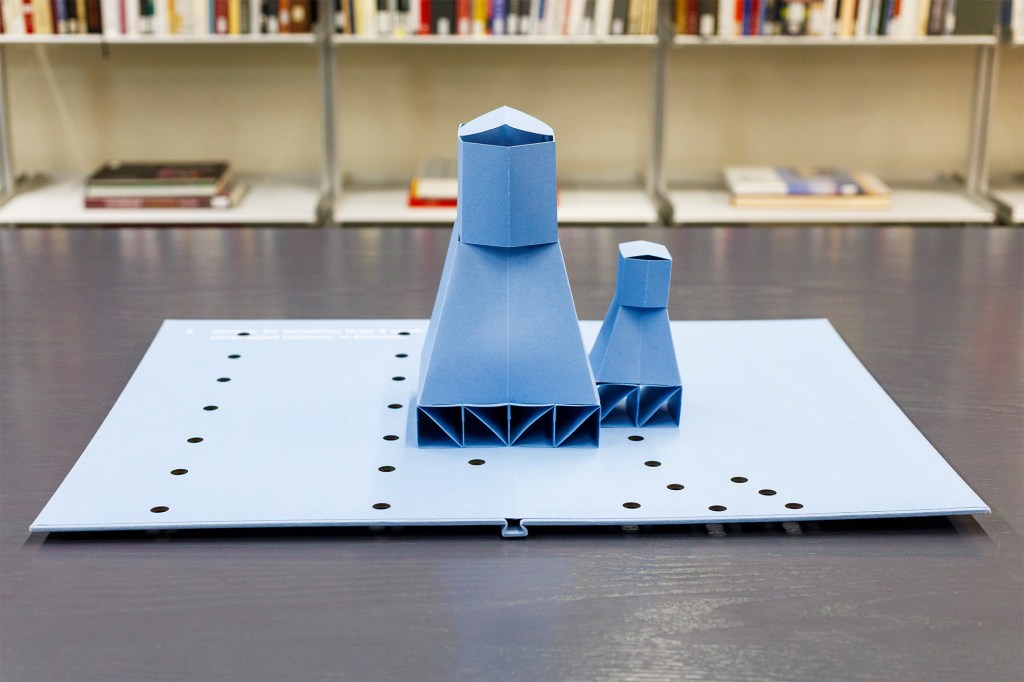

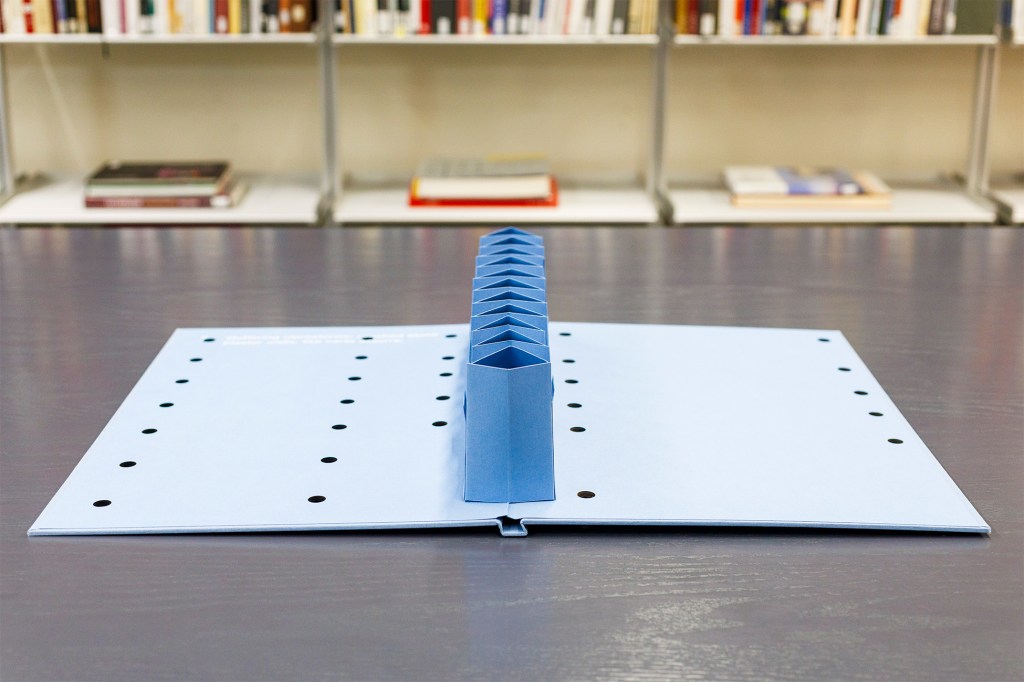

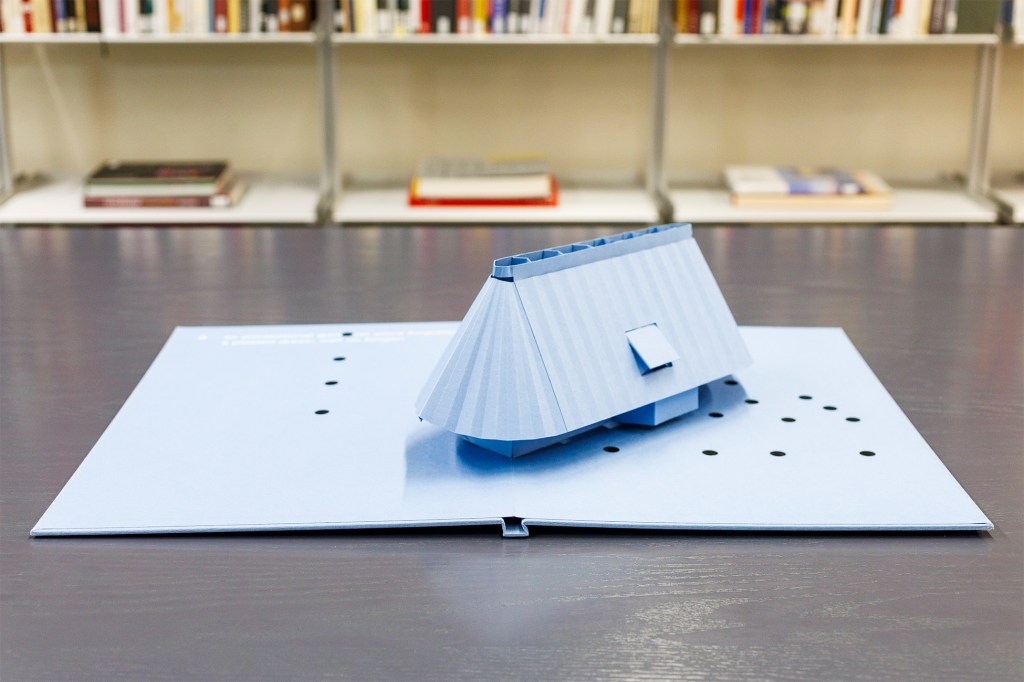

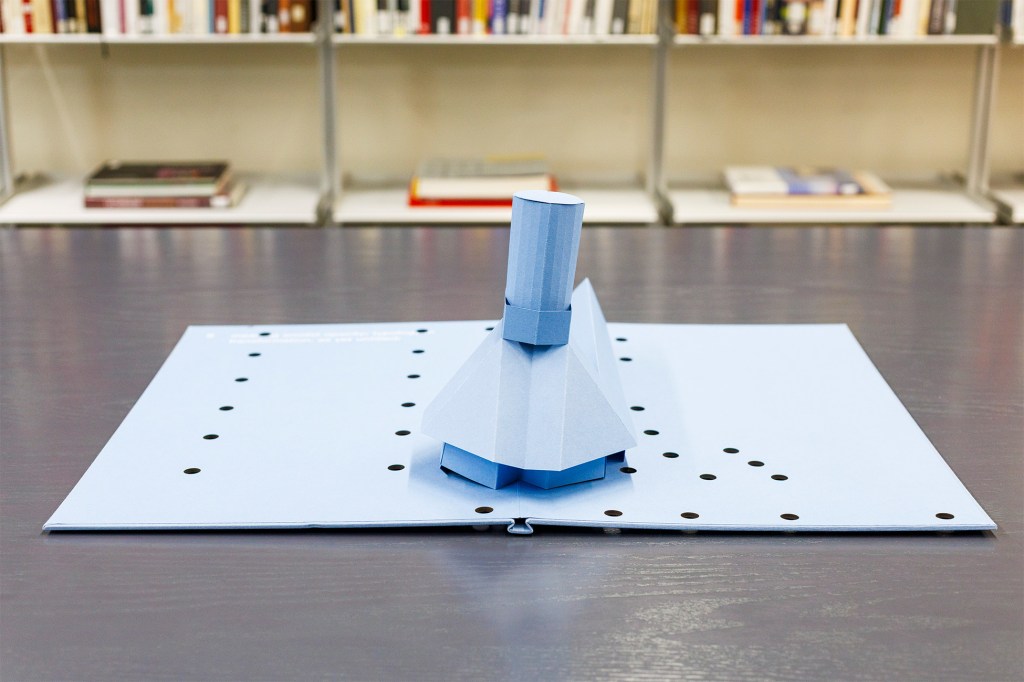

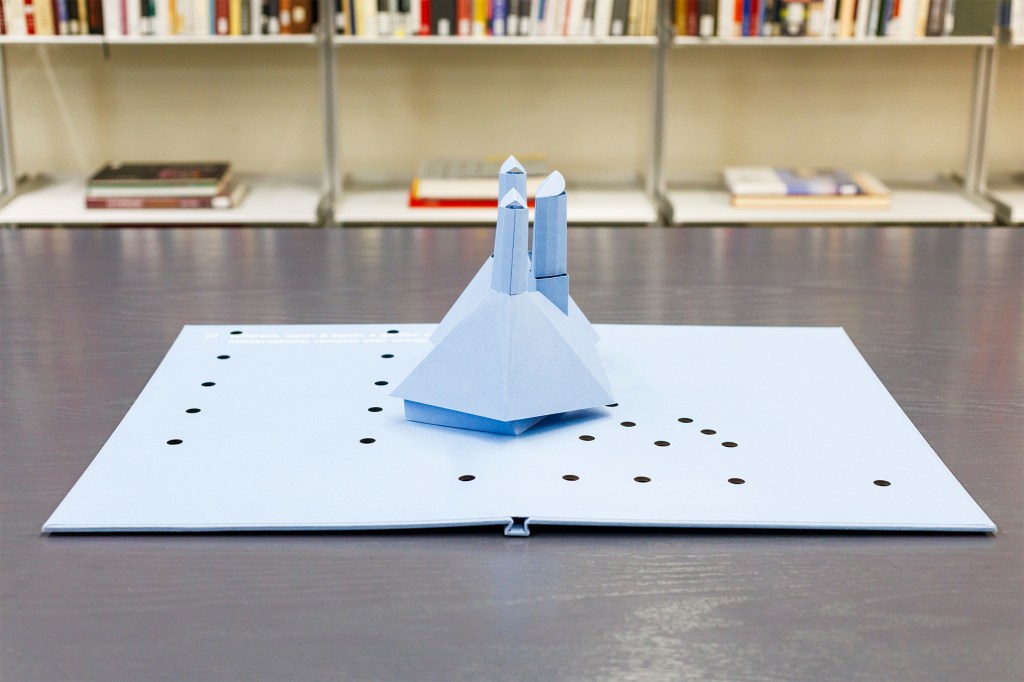

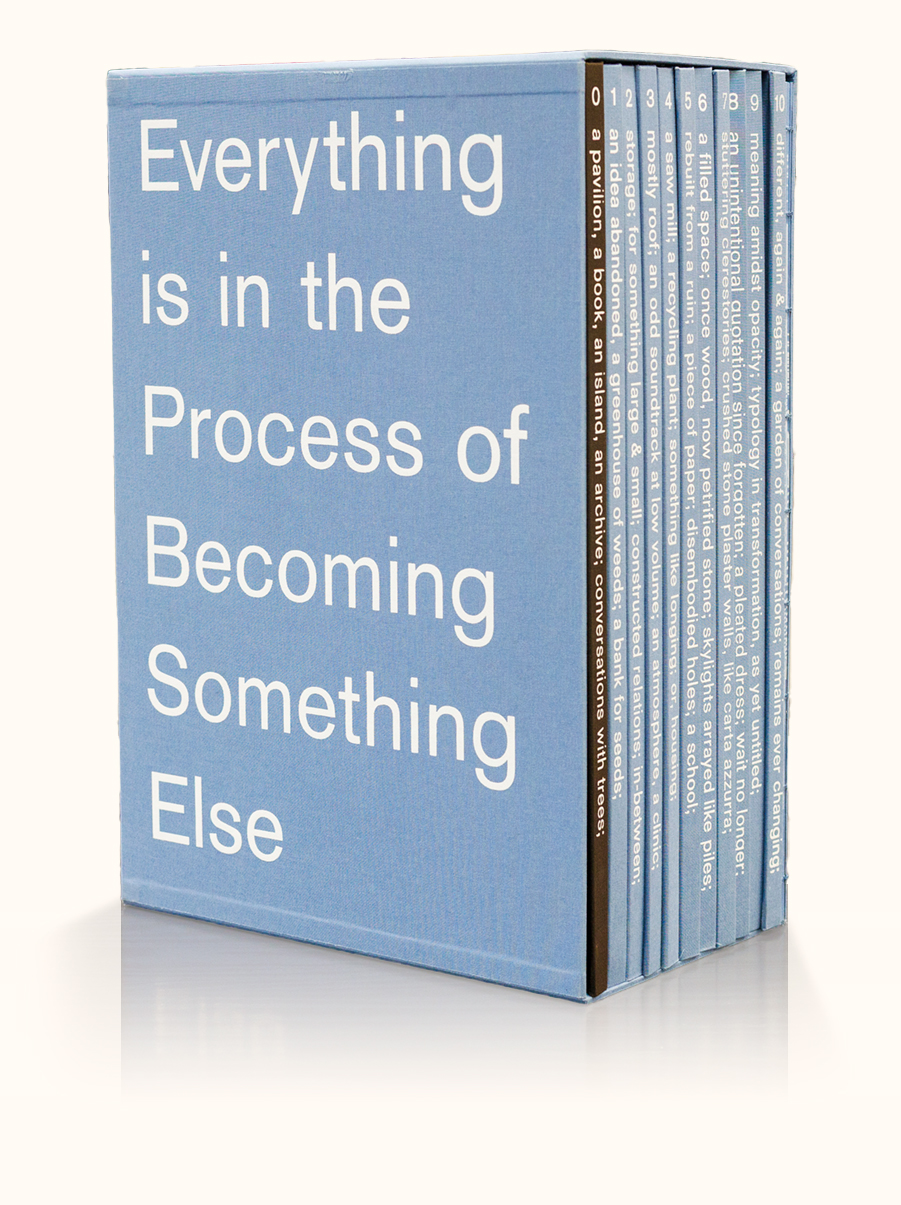

Imagining what could have been

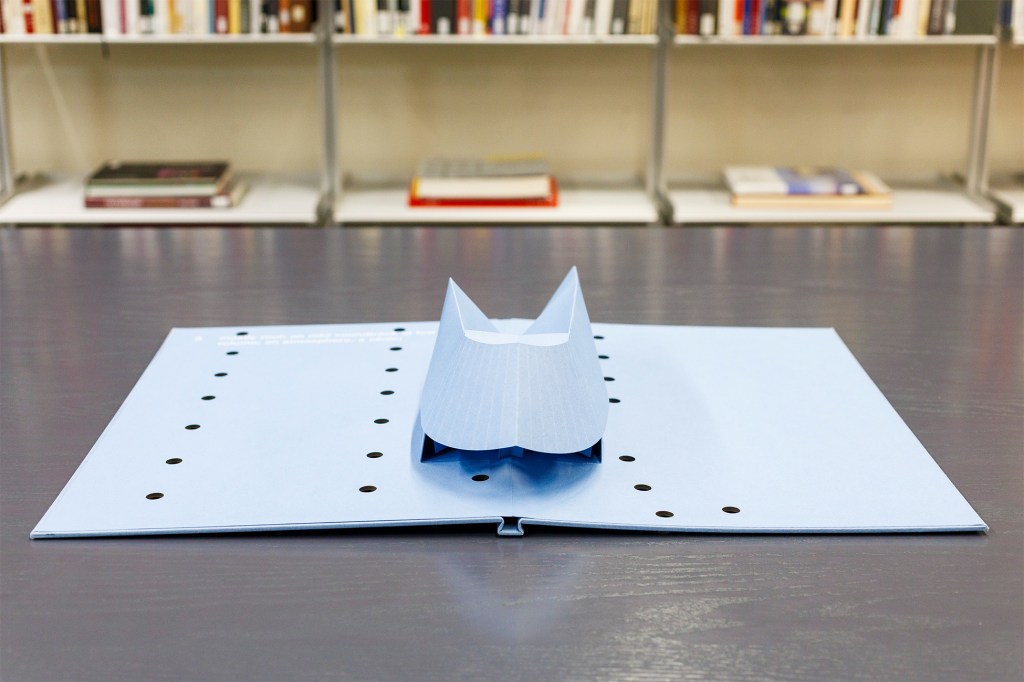

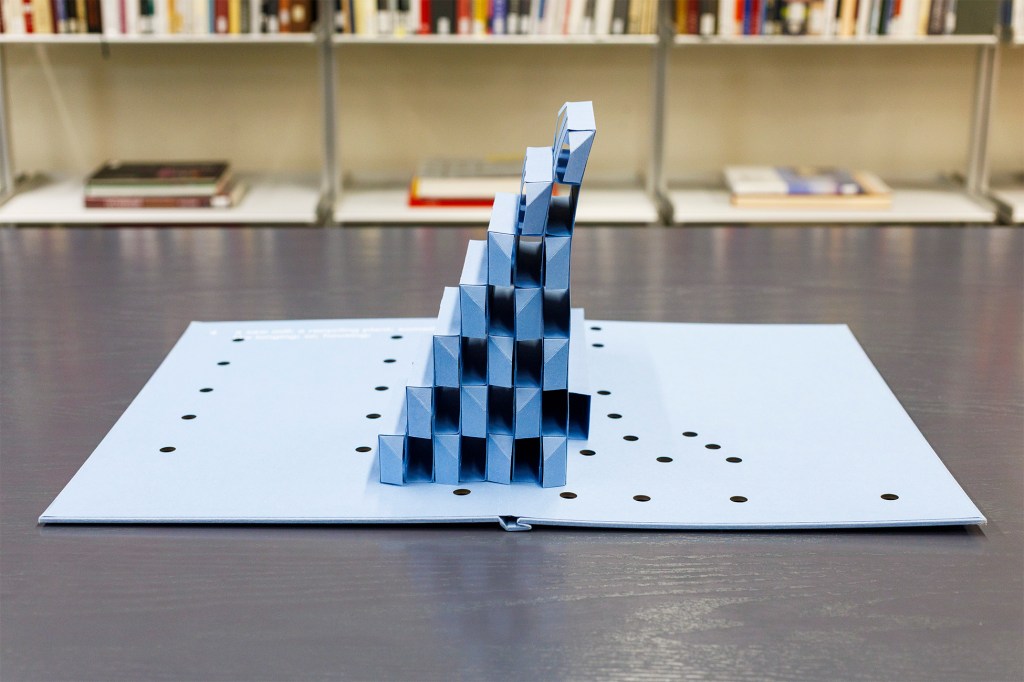

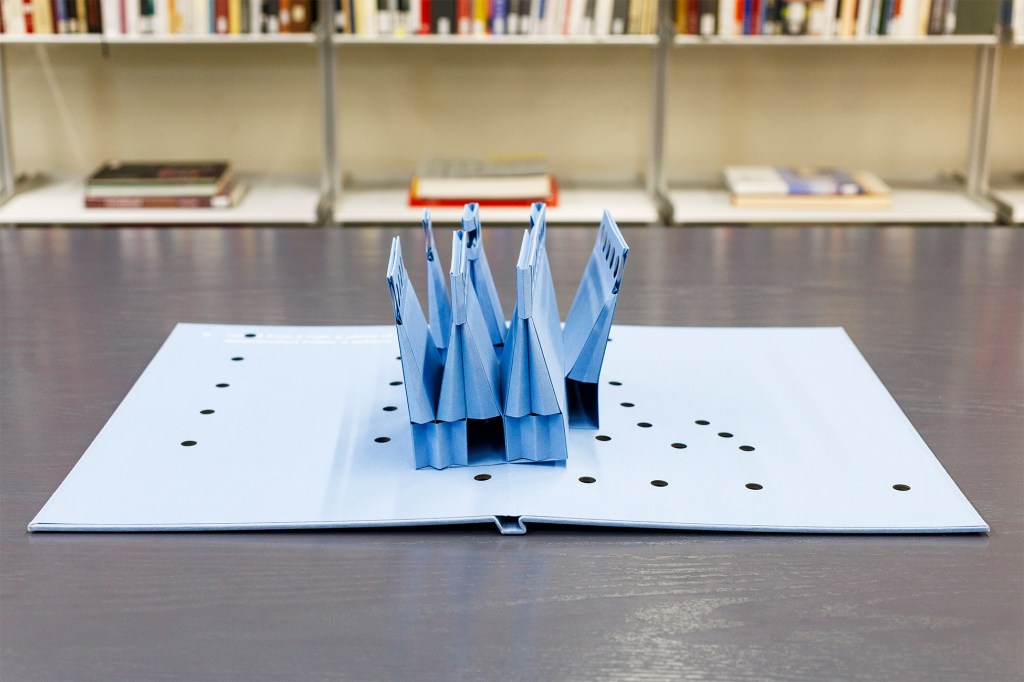

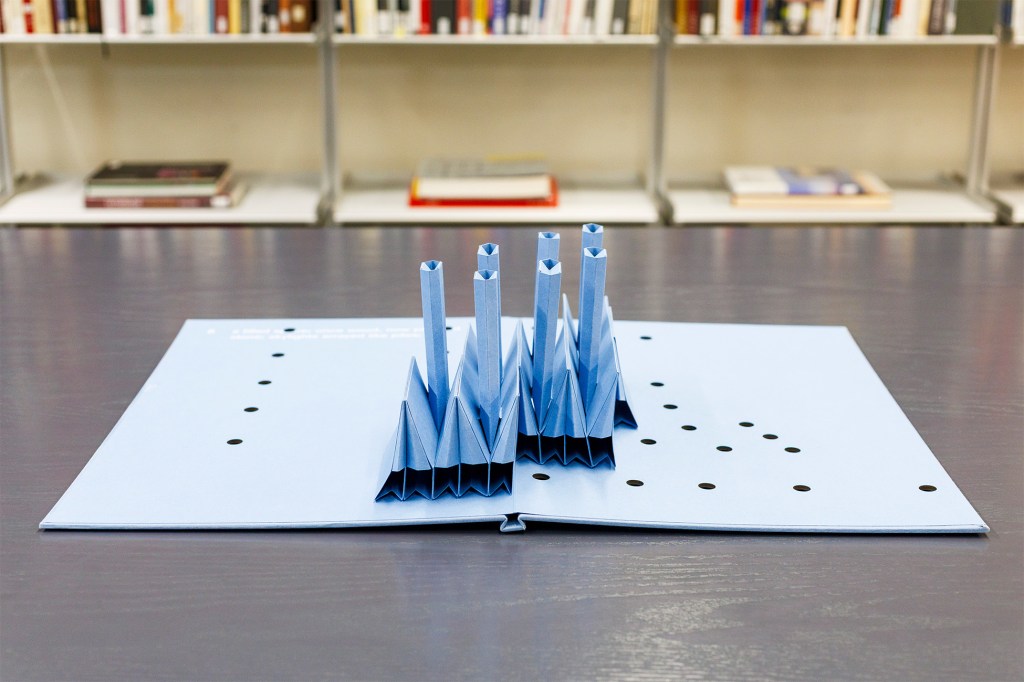

“Everything is in the Process of Becoming Something Else,” produced by architects Michael Meredith and Hilary Sample for the 2025 Venice Biennale art exhibition represents unrealized designs for the show’s Book Pavilion drawn by architect James Stirling between 1989 and 1991, as well as a model of the final design that still stands today. The volume is 12 individual books — 11 pop-up books and one containing explanatory text as well as worm’s-eye drawings for each proposed pop-up model.

“Everything is in the Process of Becoming Something Else,” by Michael Meredith and Hilary Sample.

“Architecture is a performance of constant transformation, always becoming something else,” their book reads.

Meredith graduated from the Harvard Graduate School of Design in 2000. Meejin is a 1997 graduate of the GSD.