How Barbie became the ‘It Girl’

Innovative marketing, ad strategy helps fashion doll rocket through Mad Men years and beyond, with tip of hat to Gillette

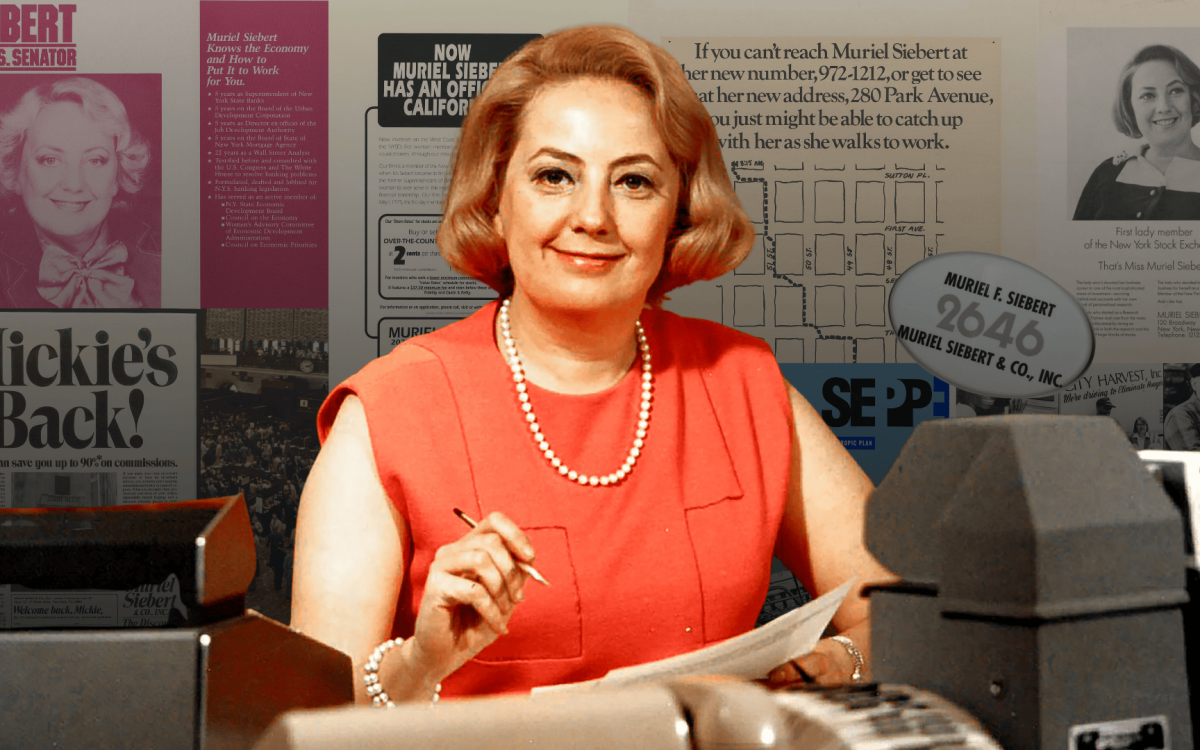

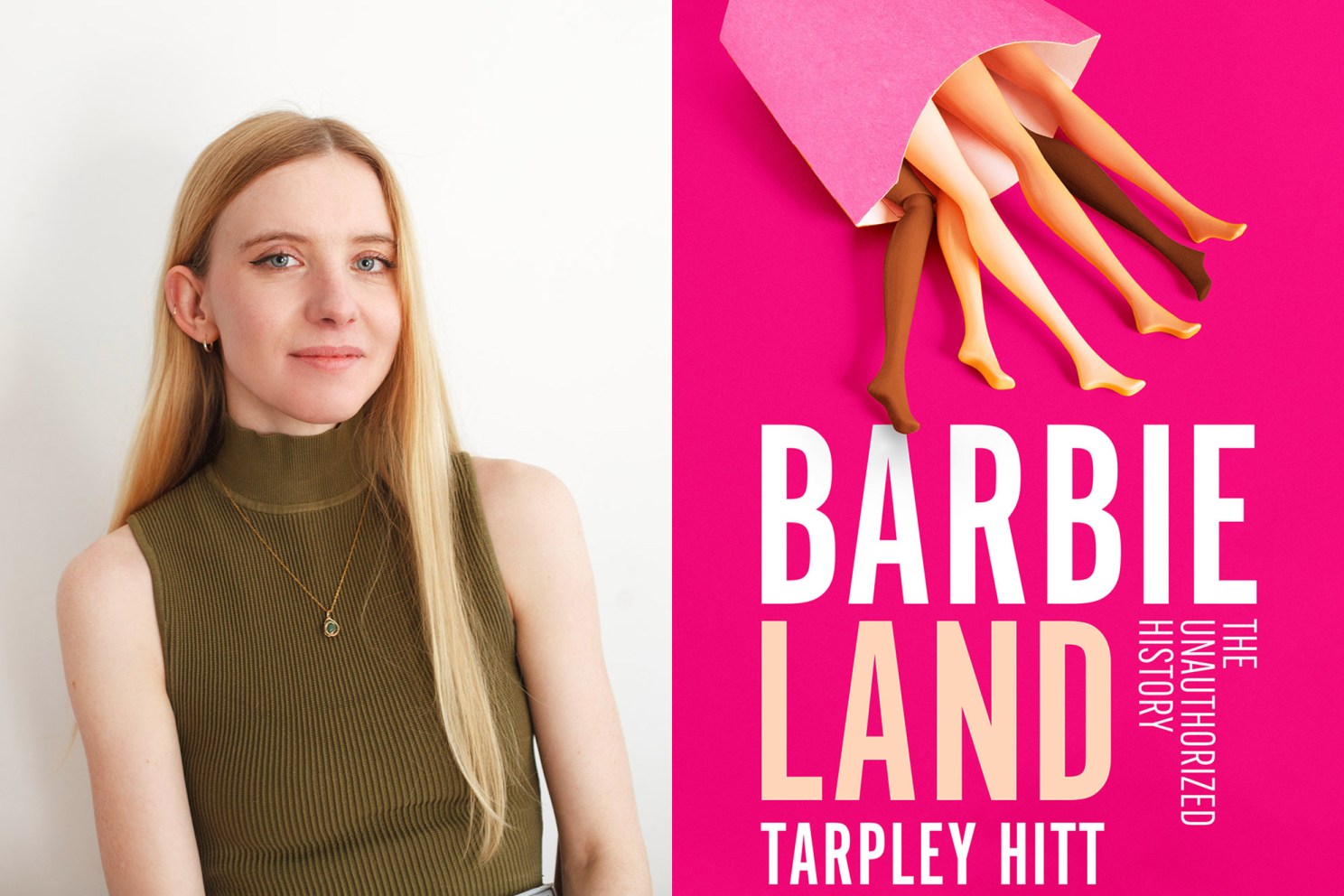

Excerpted from “Barbieland” by Tarpley Hitt ’18

King Gillette was a cork salesman and congenital tinkerer, always inventing some knickknack. Toward the end of the century, he had been working on something he hoped would be more permanent — an earnest, prescient, and intermittently hilarious tome of utopian social reform called “The Human Drift.”

The manifesto took aim at the gross inequality of the Gilded Age and laid out a plan that might “dam the golden flood which flows incessantly into the hands of the nonproducers, the interest-takers, the schemers, and the manipulators.” Gillette loathed market competition. The eternal fight for material wealth at the expense of everyone and everything else was, in his view, an “insane idea,” an “element of chaos” that could only lead to one end: “the final control of the commercial field by a few mammoth corporations.” (At one point in the book, he wrote an extended verse monologue in which Satan describes inventing capitalism to keep “alight the fires of hell.”) Gillette wanted to ensure the equitable distribution of goods and resources. But — and perhaps this is where he lost some readers — his solution was to replace all production with one unified stock corporation, run, along with the rest of society, from a gargantuan, perfectly rectangular, ceramic-tiled mega-city to be constructed near and powered by Niagara Falls.

And yet shortly after the book came out, Gillette was struck with another idea: a razor with disposable blades. “It was almost as if Karl Marx had paused between ‘The Communist Manifesto’ and ‘Das Kapital’ to develop a dissolving toothbrush,” Gillette’s biographer remarked. A decade later, after years of honing the manufacturing protocol, Gillette was awarded the first patent for a mass-produced disposable razor. In the process, he inspired a business model perhaps as influential as the device itself. His company realized they could sell the razor at a loss — luring in customers with a low-cost product — and profit instead from the marked-up blades they inevitably came back to buy. Gillette continued his writing career, self-publishing a pamphlet on a plan for universal employment and elaborating on his public corporation in two more books, one cowritten with Upton Sinclair. But in the end, Gillette became better known for his shorter writing. As his possibly apocryphal line went: “Give ’em the razor, sell ’em the blades.”

Gillette’s “razor blade model” spawned many copycats. Consumers still encounter it now, when suspiciously affordable printers beget years of extortion for ink. But the technique did not translate neatly into the world of toys. Toy manufacturers are beholden to seasonality. Men need razors year-round; offices can run out of toner cartridges any old month. But while parents may buy the odd game or doll or gun for birthday parties or the occasional treat, mass toy-buying is concentrated around the holidays. Many toy companies will spend most of the year in the red, only to enter the black in the final quarter. It was a perpetual worry for American toy makers. As early as 1916, one trade association had tried to float the idea of turning Independence Day into the toy-buying equivalent of a Christmas in July. It didn’t take off.

Seasonality remained an issue when Mattel entered the toy business, and by the time Barbie debuted, it had become a subject of great concern. If Mattel went public, as the company planned to the following year, founders Ruth and Elliott Handler would face Wall Street pressure to deliver profits, not just annually or in the months before Christmas, but every quarter. Sponsoring The Mickey Mouse Club had been an early major attempt to solve the problem. Mattel had become the first, and for a time, the only toy advertiser “to use network television 52 weeks a year.”

But Mattel’s investment in year-round advertising had attracted “many imitators,” and not just from toy makers. “Suddenly programming which used to be a TV toyland,” a Mattel memo read, was selling “candy, cookies, toothpaste, cereal, soft drinks, gym shoes, et cetera.” The Handlers worked hard to maintain their lead. But even with TV show tie-ins for every season, Mattel noted, “the majority of buying was still concentrated in the last quarter.”

But Austrian psychologist Ernest Dichter, the Handlers’ marketing consultant, had pointed out that, when it came to Barbie, the “clothes sell the doll.” His idea was to not just pitch kids on buying one or two dolls, but to bill Barbie as a talisman to what Ruth called “the World of Barbie” — not a terminal product that ends with the first sale, but something to collect, nurture, and feed with a constant supply of costumes and accessories, or risk missing the latest small shoe or bitty bag and finding their figurine comically out of date. If this “‘collection’ type sequence is promoted,” Dichter wrote, “continued purchases could be encouraged.” The Handlers embraced Gillette’s razor blade technique — but Mattel did it even better. Barbie wasn’t free, or even, in the grand scheme of toy price points, especially cheap (a $3 doll, adjusted for inflation, would now run about $32). And yet she had the same effect. In lieu of the dead-ends of toy companies past, Mattel continued creating new stars in the Barbie cosmos, offering a collection kids could never complete. Internally, staff would call her: “Our Lady of the Perpetual Income.”

By Barbie’s first birthday, Mattel had already sold some 351,000 Barbies, and “several hundred thousand” outfits, prompting such an order backlog that they ran out of their first edition — the coveted model collectors call the “No. 1 Ponytail” — and started putting out No. 2 (which featured a lighter, plastic stand), then No. 3 (which sported a softened brow). By 1961, when No. 5 came out (featuring a hollower, and thus cheaper, body), Barbie’s wardrobe included three dozen costumes. Her hair came in blonde, brown-black, and “Titian red,” styled with curly bangs or in a Jackie Kennedy−inspired “Bubble Cut.” Barbie had become so popular that she started to get fan mail, as her German inspiration Lilli once had. Soon, Ruth gave Barbie a plus-one. As a press release announced in August: “Mattel Creates Ken, Boyfriend for Barbie.”

Ken followed the Barbie format, debuting with his own collectible accoutrements, selling so successfully that other companies copied the idea. In 1964, three years after Ken’s debut, the rival toy maker Hasbro introduced its own boy doll, whose accessories included a literal long rifle, G.I. Joe. He was billed, not as a doll, but as “an action figure.” Ken was just the beginning. Over the sixties, Barbie’s social network grew to include her friend Midge, who came in four hair colors; Ken’s friend Allan, whose sole selling point was that he fit in Ken’s clothes (slogan: “All of Ken’s Clothes Fit Him”); a younger sister, Skipper, who introduced junior versions of Barbie’s outfits; Skipper’s two friends, Skooter and Ricky; and a cousin named Francie, the first Mattel doll to come as both white and black. Soon, Barbie acquired two new twin siblings, Tutti and Todd; Tutti’s friend Chris; four more friends, Casey, Stacey, Twiggy — based on the distinctly unbusty model of the era — and Christie, the second black doll in the Barbie canon, but the first to be given her own name.

As Barbie’s social scene grew, so did her résumé, adding gigs as a fashion designer, singer, flight attendant, ballerina, and nurse. She became a “career girl” in 1963, and a “drum majorette” the year after. Her professional ascent endowed her with new marketable skills. “Miss Barbie” introduced bendable legs. “Color Magic Barbie” could use a special solution to dye her hair. And “Talking Barbie” gave the doll, suffering in silence for nine years, her first words. (Among them: “I love being a fashion model.”) Ken evolved in his own way too. The first iteration, which had three-dimensional hair, turned out to suffer from male pattern baldness when washed. Mattel secured his successor’s hairline by coloring it onto his scalp.

Barbie and friends had a range of transit to choose from, including a Ken’s red hot-rod, Barbie’s lilac convertible, a lime-green speedboat, and a blue “sports plane.” At night, they could curl up in the first Barbie Dreamhouse, initially a cardboard single-story home, in a ranch style with red plaid drapes and “mid-century wood grains.” Barbie enthusiasts could join the “Official National Barbie Fan Club,” read Barbie short stories in the official Barbie magazine, or dive into longer Barbie novels via several Random House Barbie books. Barbie herself was a reader. One doll came with three knuckle-sized manuals: “How to Travel,” “How to Get a Raise,” and “How to Lose Weight.” The last one advised: “Don’t eat!”

Barbie’s success was contagious. “She was a merchandiser’s dream,” an Esquire article noted, “a mixture of precocious sex and instant affluence.” Mattel licensed the Barbie name liberally and devised their own products too. The market flooded with Barbie-adjacent goods: Barbie bubble baths, Barbie suitcases, Barbie bedspreads, Barbie diaries, Barbie record players, Barbie records, Barbie beds, Barbie cars, Barbie friendship rings, Barbie lockets, Barbie makeup, Barbie books, Barbie comic books, Barbie puzzles, Barbie greeting cards, Barbie thermoses, Barbie lockets, Barbie pencil cases, Barbie lunch boxes, Barbie tea sets, Barbie clothing patterns, Barbie umbrellas, and, to bring it full circle, Barbie paper dolls. In a speech on merchandising, Ruth announced: “The name Barbie is magic.”

As Barbie expanded, so did Mattel. The company went public in 1960, the year after her debut, with a small offering of over-the-counter stocks — shares that were “quickly spoken for.” By early 1962, Mattel was raking in nearly $50 million in annual sales, a record they were “well ahead of” before Christmas. The next August, Mattel debuted on the New York Stock Exchange. In 1964, Mattel opened new factories in Los Angeles, Canada, and New Jersey. They set up a sales office in Geneva, Switzerland, and a new headquarters building in Hawthorne, California.

The company was growing fast and unchecked, but each new spurt seemed to only multiply sales. “We were gutsy people,” Ruth said. “We were young and full of fire and cocky and everything worked.” Mattel had hit on a formula, The Wall Street Journal drooled: “once a toy craze has been created, ride it for all it’s worth with an endless proliferation of new items tied to the original product.” Mattel expanded its product line by some 50 percent in 1965 —then “the biggest increase in the company’s history.” That year, sales topped $100 million. They were making so much money, they seemed to barely know what to do with it. At one point, just to keep their retailers in good spirits, the company spent two years and “well into six figures” producing an all-male original musical called “Mattelzapoppin’” — then toured it to some 8,000 toy buyers across 27 different cities. One Christmas, the R&D Department splurged on thousands of frozen turkeys — one for every employee. When the staff got a little buzzed at the office party, they began “clobbering each other with the rock-hard birds.”

The mood at Mattel was one of “near euphoria,” a reporter observed, “a feeling that Mattel had the Midas touch.” It seemed the Handlers could do no wrong. “Mattel is energetic, deep-thinking, and far and away above the field in product development,” a Chicago toy buyer told the Journal. “I simply can’t see its downfall.”

Copyright © 2025 by Tarpley Hitt. Reprinted by permission of One Signal Publishers / Atria Books, a division of Simon & Schuster, LLC.